|

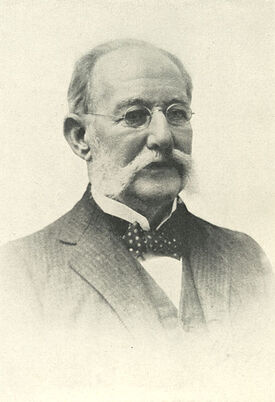

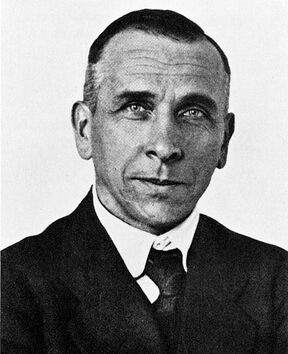

Some people argue that science is too conservative and set in its ways. They claim that science favors a herd mentality where scientists are rewarded for following the mainline theories and are penalized for dissent against the establishment. It is argued that this creates a hostile environment for radical new ideas that hinders scientific progress and slows down innovation. Is this true? Let’s look at 3 of these ideas that were rejected by science but turned out to be true.  Carlos Finlay Carlos Finlay Mosquitoes transmit Yellow Fever At the end of the 19th century, diseases were considered to be transmitted through person to person contact, but the mechanisms of the transmission of diseases like Yellow Fever eluded scientists. The Cuban physician, Carlos Finlay, developed a theory that Yellow Fever was transmitted by mosquitoes, and he performed studies where he had a partial success in having some volunteers bitten by mosquitoes develop mild cases of Yellow Fever. Finlay presented this idea to the scientific community in Cuba in 1881 and later in the United States. However, Finlay’s evidence turned out to be problematic, generating many unanswered questions, and his presentation was less than stellar. His idea was met with derision and he was called a crank. For nearly 20 years he persevered in his research, which he funded himself, and continued generating stronger evidence and publishing it. During this time, the Scottish physician, Patrick Manson proposed (based on his earlier work on the transmission of a disease-causing worm by mosquitoes) in 1894 that the malaria parasite could be also be spread by these insects. A few years later the British medical doctor, Ronald Ross, proved that this was indeed the case. Towards the end of the century, Finlay’s idea started looking less farfetched and gained enough notoriety to warrant it be put to test. In 1900 Walter Reed carried out his famous experiments in Cuba that demonstrated that mosquitoes transmit Yellow Fever, and Finley was vindicated.  Alfred Wegener Alfred Wegener Continents Move In 1912 the German geophysicist and meteorologist, Alfred Wegener, proposed the idea that the continents of the Earth are moving away from each other, and that they were once joined together into a great landmass he called Pangea. His evidence consisted of how the shape of the continents could be made to fit together like pieces of a puzzle, the distribution of both current and fossil species across continents, and how the geological strata in one continent matched those of others. Unfortunately, not only did Wegener lack a credible mechanism to explain this proposed continental movement, but he made several mistakes including overestimating the rates of movement. His idea of continental drift was panned by the scientific establishment and labelled a “fantasy” and “pseudoscience”, and he was publicly ridiculed. Through all this, Wegener persevered, refining his ideas and correcting his mistakes. However, it was only in the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of the new science of paleomagnetism, that numerous studies demonstrated that the seafloor indeed was spreading and that the continents were moving. Sadly, Wegener died during an expedition to Greenland in 1930 and did not live to see his idea incorporated into the modern theory of plate tectonics. Today the movement of continents can be measured with satellites.  Stanley Prusiner Stanley Prusiner An infectious Agent with no DNA or RNA There are diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or kuru that back in the 1970s were thought to be caused by viruses that act very slowly. The American neurologist and biochemist, Stanley Prusiner, became interested in these slow virus diseases and managed to isolate pure preparations of the infectious agent. Prusiner found that these preparations contained protein but were devoid of nucleic acids (nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA carry the genetic information in all living things including viruses), and that agents that destroyed proteins but not nucleic acids eliminated the infectivity of the preparations. Therefore Prusiner concluded, based only on this evidence, that the infectious agent was a new infectious entity made up solely of protein. He proceeded to publish an article where he not only claimed to have discovered a new infectious agent unlike any found before, but he also christened this agent, prion, a name put together from the words “proteinaceous” and “infective “ (although “proteinaceous” and “infective” should yield “proin”, “prion” sounded better). The vast majority of scientists did not accept his idea, which at the time went against everything that was known about the nature of infectious agents, and a good number of them heaped vitriol upon Prusiner. The fact that Prusiner was a stellar networker and salesman of his ideas and managed to get multimillion dollar grants did not soften their attitude. Although Prusiner kept researching and making new discoveries about prions, experiments in this field used to take years, so scientists were slow to try to reproduce his experiments. Eventually others were able to replicate his results and the concept of prions was accepted. Prusiner won the Nobel Prize in 1997. Now let's go back to our question. Does science create a hostile environment for radical new ideas that hinders scientific progress and slows down innovation? Two things have to be understood about radical new ideas in science: 1) the majority of radical new ideas turn out to be wrong, and 2) there is usually not one or two of these radical new ideas but dozens of them. Which ones are correct and which ones aren't? Should the limited funds allocated for science be made available to everyone who has a radical new idea? The answer is, of course, No. Decisions have to be made as to which ideas are more plausible than others. Science tends to give preeminence to that which is established. If you want to upend established science, the burden of proof is on you. The truth is that the radical news ideas of Finlay, Wegener, and Prusiner were not backed by convincing evidence. Their evidence generated more questions than answers, and scientists were not moved to throw orthodoxy out the window, at least right away. The insults and humiliations that Finley, Wegener, and Prusiner endured are certainly regrettable and objectionable, but this has to do more with human nature than with science. However, as more and better evidence was generated, questions were answered, errors were corrected, and experimental results were replicated, their ideas were accepted. They were right, and the establishment was wrong. But let’s be clear on something, the initial rejection of their ideas was totally warranted, even if they did turn out to be true. The photos of Carlos Finlay and Stanley Prusiner, and the photo of Alfred Wegener from the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg are all in the public domain.

8 Comments

Erik Maronde

2/28/2020 12:23:08 am

Prisoner (and Gajdusek) were so lucky to live long enough to see their ideas accepted. Very nice article!

Reply

Rolando Garcia

3/16/2020 02:16:02 pm

Thanks for your comment, Erik.

Reply

Dave Paul

4/14/2020 10:21:39 am

Thank You for this wonderful information.

Reply

Rolando Garcia

4/18/2020 08:07:19 am

Thank you for your comment, Paul. I'm glad the information was useful for you.

Reply

Stephen B Baines

4/17/2020 05:06:43 pm

This is a good post. I have been thinking about writing about something like this for a while now.

Reply

Rolando Garcia

4/18/2020 08:11:11 am

Thanks for your comment, Stephen. You should go ahead and write it. There are many aspects, variations, and examples regarding this issue that can be researched and addressed.

Reply

Marika Elek

5/1/2020 01:45:41 pm

You can also add Ignaz Semmelweis, who brought in antiseptic methods to save women from childbirth fever.

Reply

Rolando garcia

5/19/2020 06:09:09 pm

Thanks for your comment, Marika. His case was a sad one. Sometimes being right is not enough.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed