Most people are interested in science and they admire and respect scientists, but I’ve noticed that some folks exhibit one of two extreme reactions. 1) Self-Disparaging: Scientists are smart. They talk about all these things and use all these words, and I can’t figure out what they are saying. Therefore I’m stupid. I was once trying to explain to a person not educated in science a specific scientific issue. I was trying to describe things in a manner as simple as possible, but I didn’t seem to be having much luck in getting the point across. In the end the person excused himself for not understanding what I was talking about, and then he added, “I’m stupid”. Whereas some individuals, like the one I described, state outright that their intellect is defective, or at least not up to par, others get defensive and either try to bluff their way through a conversation involving science or try to avoid it all together. Sometimes I even sense an animosity, an unspoken tension, or hostility when a scientist is around. It’s like some people are concerned that they will be exposed as not knowing enough or as not being smart enough. 2) Dismissive: Scientists seem smart, but it’s really all talk and jargon. Anyone can be as smart as scientists and talk science and read and quote scientific studies. Not only that, scientists are often beholden to the interests of governmental or other institutions that fund their research, and they lie, misrepresent, or fake their results when their data don’t fit the facts to keep on being funded. Due to the nature of my blog, I have had several exchanges with creationists, anti-vaccination advocates, conspiracy theorists, climate change deniers, and so forth. These individuals believe they know more than the experts who have dedicated their lives to understanding a particular scientific field. These people normally laugh my replies off with off base comments filled with little emoticons and links to junk science sites or lists of scientific articles of low quality. I want to state here that both extremes are wrong. I believe the first extreme exists due to the popular perception of what being smart means, its value to society, and how scientists tally up to this perception. Regarding this, I want to make the following points: 1) As I have posted before, intelligence has many components. The fact that one person excels in one of these components does not make him/her smarter than those that excel in others. 2) There is nothing magical of mysterious about being a scientist. Although, science can be performed at several levels, the basic qualification required to be a scientist is to think like a scientist. Anyone who does that can be a scientist. 3) We all have areas of specialization on which we have become knowledgeable. A climate scientist may know a lot about global warming but they may not make the best salesperson, farmer, restaurant manager, secretary, truck driver, accountant, etc. 4) We must not dismiss the knowledge we have of our particular area of expertise compared to others. Being a librarian may not look important compared to working at NASA shooting satellites into space, but we all fulfil a role in society and benefit groups of people with our work. 5) For scientists, explaining what we do to people who are not knowledgeable in science is very important. A key component of being “smart” is finding a way to get the point across. As a scientist, when I cannot explain some important scientific issue adequately to my audience, I consider it my failing, not that of my audience. The flipside of the first extreme is the other extreme which I believe in recent times has been fueled partly by the vitriol unleashed against scientists by those aligned with special interests, or those subscribing to notions that scientists are dishonest or sold to government agencies or corporations. Regarding this, I want to make the following points: 1) When a person has dedicated their life to learning and studying an area of human knowledge such as a scientific discipline, this has to count for something. If you are not an expert in that area, suggesting that you know more than the experts is not only foolhardy but also disrespectful. This is nothing germane to scientists, as it also applies to any area of human expertise. 2) The scientific consensus achieved regarding issues such as climate change or the safety of vaccination is supported by many scientists from different countries and ethnicities who have different political, social, philosophical, and religious persuasions. They all agree because they have been finding the same things. It is risible to suggest that ALL these scientists have sold out in some sort of global conspiracy. 3) Scientists are human beings, and as such they can have moral or ethical failings and harbor contradictions. No one denies that. Most scientists are moral and ethical persons, or at least they try to be, and just like other groups of people in the overall population, the transgressions of a few individuals do not bear on the majority of scientists. So to recap, yes, scientists are smart and they know a lot, but even if you do not understand many aspects of science, you also are smart and have specialized knowledge about your own area of expertise that is useful to society. Additionally, scientists have the responsibility of explaining science to non-specialists in a way that is accessible to them and that will better equip them as members of society to deal with issues like the climate change and vaccination controversies. Finally, scientists, like other professionals in our society, also are worthy of respect and should be recognized for their merits and judged on their individual actions. As with many things in life, we are better served by avoiding the extremes. The image is a public domain picture from Pixabay free for commercial use.

0 Comments

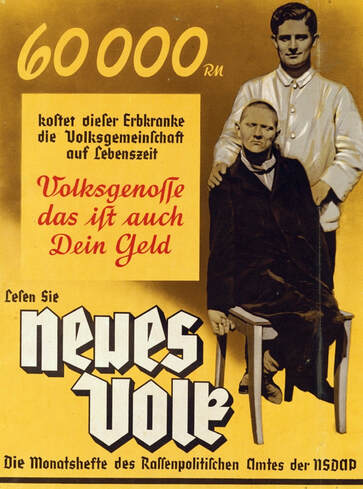

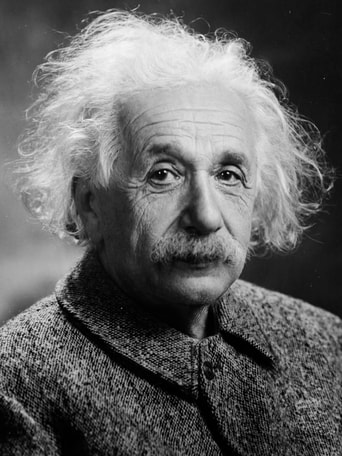

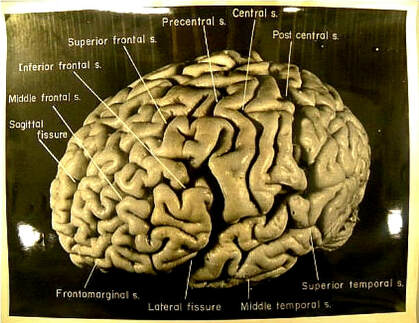

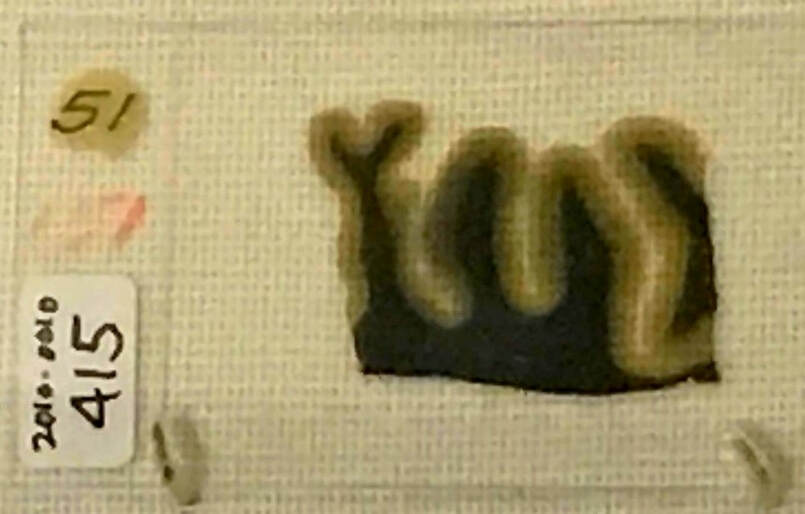

People think about intelligence based on its association with the extremes. On one side there are individuals who achieved fame for excelling in their fields. So clearly Nobel Prize winners like Albert Einstein or millionaires like Warren Buffett are very intelligent. These are the geniuses. At the other end of the scale, there are individuals who struggle with the intellectual challenges of everyday life. These people (in these enlightened times) are said to have “intellectual disabilities”. And in between these extremes you find people who are able to function normally and excel to a lesser or greater extent in their communities, their work, and their social life. These are people like you and me: the average folk. To most people, it seems obvious that there is a significant difference in intelligence between the average folk and the geniuses, or between the average folk and those with intellectual disabilities. It also seems equally obvious that these differences have real-world consequences. These are notions that most people accept. What is unwarranted, however, is the next level in this sequence of reasoning. This is the notion that, just as there are significant differences in intelligence between the extremes and the middle that have real-world consequences, there also are differences in intelligence among average folk that are significant and have similar consequences. If this were just merely a notion, there would not be an issue, but because intelligence is what makes us unique among all living things, we are fascinated by it. We want to know what it is. We want to define it. We want to grasp it. We want to dissect it. We want to measure it. We want to reproduce it. In order to do this, we have to assume that intelligence is something tangible that can be defined, grasped, and measured. Through several iterations in our attempts to quantitate intelligence (that have included the likes of follies such as cranial capacity) we have arrived at the notion that intelligence is the ability to solve problems, and therefore that intelligence can be “measured” by how well a person performs in solving a series of problems presented to them: the so-called intelligence tests. These tests were originally conceived to identify students who required extra help in school environments, not to ask how intelligent these children were. The tests were also used to gauge whether therapies or interventions were being successful at improving the students’ conditions. However, soon versions of these tests began to be applied to adults and otherwise normal individuals, and were used to produce a single number which would rank people from least to more intelligent. Here is where the problems arise. The general public has to understand that intelligence tests have two serious limitations when it comes to the assessment of intelligence. One limitation of these tests is that they are not useful for assessing differences among otherwise normal individuals or groups of normal individuals. A large difference in intelligence test scores between a genius and an average person has an obvious interpretation (the genius is more intelligent), but a smaller difference in intelligence test scores among average individuals cannot be interpreted so readily in terms of their real-world impact. It has been found, for example, that among people with equal levels of education, the performance in intelligence tests is a poor predictor of job performance, occupational standing, earnings, or wealth. Nevertheless, it is telling that we often associate being intelligent with being famous, amassing a fortune, or winning a Nobel Prize. However, what about being a moral and ethical individual, being a good parent, being active in the community, being a good friend, organizing for social action, etc.? A person who excels in these activities may not be labeled a genius or become rich or famous, but can anyone seriously argue that having the intellect to be successful in these activities does not require a substantial amount of intelligence? This issue leads us to the second and most serious limitation of intelligence tests, namely the fact that they only assess a limited aspect of what we call intelligence. There is strong evidence that human intelligence is not one thing, but rather that it is made up of several independent components which are in turn associated with multiple brain operational networks. This means that intelligence is an emergent property of several human abilities, and it cannot be reduced to a single number that measures how intelligent someone is. For example, someone can be very intelligent and use this intelligence to figure out how to rob a bank, make an illegal drug, or kill a person. However, many would argue that doing these things is very unwise. Shouldn’t wisdom be considered part of intelligence? Another example is sociability. What about people that know how to fit in and get along with others? What about people who know what to say, when to say it, where to say it, how to say it, and whom to say it to? There are very smart individuals that are socially awkward or disdainful of others they regard as inferior and unable to fit within a social structure or work in a team. Should sociability be considered part of intelligence? The representation of a person’s intelligence that we obtain from intelligence tests is at best incomplete and at worse biased. In fact some researchers in the area of intelligence think that the only thing intelligence tests evaluate is how well you perform at taking intelligence tests!  Nazi poster highlighting the high cost of caring for people with hereditary illness Nazi poster highlighting the high cost of caring for people with hereditary illness Because intelligence is so central to the human species and because of the notions that most people harbor about intelligence, the potential for the misuse of intelligence test results is great. Very few people would argue that it is not desirable to be more intelligent, and there is a stigma associated with being in the low end of the intelligence spectrum. Remember that individuals with intellectual disabilities were once formally referred to as “idiots”, “imbeciles”, or “morons”. Most people consider the opposite of intelligent to be “dumb”. These people also believe that “less intelligent” is synonymous with “dumber”. When groups of people are found by intelligence tests to score lower than other groups, in the eyes of many the lower scores implies “dumber”. Once that step is taken, the transition from “dumber” to “inferior” is all too easy and common. And from here, the dark and twisted history of our efforts to assess intelligence has produced abominations ranging from forced sterilization of individuals and restrictions in immigration in countries like the United States, to outright killing of those judged to be feeble minded in places like Nazi Germany. Even today, intelligence testing differences among races are being used to argue for the intellectual superiority of one race over others. Research into the nature of intelligence is a valid scientific endeavor, and the restricted application of intelligence tests to very specific situations can be beneficial. But expanding the application of intelligence tests to otherwise normal individuals coupled with inaccurate notions harbored by the general public regarding how these tests work and what they mean, can fuel discrimination and racism. It has happened in the past and it can happen again. The brain image from Pixabay is free for commercial use. The Nazi poster by the Neues Volk ("New People") magazine published by the Rassepolitischen Amt der NSDAP (Office of Racial Policy of the Nazi Party) around 1937 is in the public domain.  Albert Einstein Albert Einstein Albert Einstein was one of the towering figures of the twentieth century. Images of his face surrounded by a fluffy mat of white hair have become synonymous with genius in both popular and scientific cultural circles. Einstein’s contributions in many areas of physics range from the explanation of the photoelectric effect, the equivalence of energy and mass as defined in his famous E = MC2 equation, his reinterpretation of Newtonian mechanics (special theory of relativity), and his description of gravity as a property of space and time (general theory of relativity), to his work towards elucidating the nature of light, the existence of the atom, and the establishment of quantum mechanics. He predicted the existence of Bose-Einstein condensates, gravitational lensing, and gravitational waves, all of which have been confirmed. Einstein’s ideas resulted in practical applications in areas such as nuclear power, space travel, fiber optics, GPS, and computers, but his thinking has also influenced disciplines as varied as philosophy, art, and literature. It is not an overstatement to assert that this individual changed the world. As we stand in awe admiring Einstein’s accomplishments, we wonder where all that came from. Ideas, inspiration, and creativity are attributes that we associate with one organ in the body: the brain. Therefore, if Einstein was able to think all of these things up, but most other human beings are incapable of such feats, it follows that there must be something special about Einstein’s brain: something that differentiates it from the brain of common individuals, something that makes him vastly smarter. The reasoning then goes: if we find that something, that difference between Einstein’s brain and the brain of common folk, we will have found the nature of genius, the seat of intelligence.  Einstein's Brain Einstein's Brain Einstein may have been curious about the above line of reasoning, but there is one thing we know for certain: he was aware of his fame, and he did not want to be idolized after his death. He left instructions that his body be cremated and his ashes scattered. However, when Einstein died in 1955, the temptation was too much for the Princeton Hospital pathologist that performed the autopsy; Thomas Harvey. Going against the wishes of Einstein’s family, Harvey removed Einstein’s brain. When the family found out, there was some acrimony, but Harvey managed to obtain permission from Einstein’s oldest son to keep the brain as long as it was used for scientific studies. When the hospital administrator found out what he did, Harvey was fired. He went on to practice medicine but eventually was not able to renew his medical license. His marriage ended in divorce, and he ended up working on the assembly line of a plastics factory to pay his bills. Harvey took pictures and measurements of Einstein’s brain, and he had parts of the brain sectioned into many pieces that were treated with dyes and sealed in slides. Over the span of decades, he tried to get scientists interested in looking at the brain, but found few takers. He sent slides to several eminent scientists, but they found nothing out of the ordinary. Eventually, a few scientists became interested enough to perform detailed studies of the morphology of the brain using the slides and photos of the intact brain that Harvey had taken, and some differences were found when comparing Einstein’s brain to those of regular people. However, whether these differences are related to Einstein’s intellectual prowess, or whether they are part of normal brain to brain variation that can be encountered among individuals, is still an open question. There is the possibility that genius is not correlated with an obvious gross morphological characteristic of brains, but rather to the more subtle ways in which its billions of neurons are interconnected. There is also the possibility that genius resides in the temporal and spatial pattern in which the neurons interact with each other. If this is the case, it is likely that nothing can be learned about genius from fixed dead brains, as only detailed imaging of living brains will reveal their secrets. Today, the physiological roots of intelligence and genius remain as elusive as ever. And perhaps that is a good thing. Since human beings began to study the brain, we have woven fanciful explanations as to the nature of intelligence. First brain size was the metric that was thought to be related to intelligence. Thus, when evidence was produced that some races had different brain sizes than others, this became the linchpin of ideas regarding the superiority and inferiority of these races. When the idea that brain size among normal human beings was correlated to intelligence fell into disrepute, we developed the idea that we could test for intelligence and reduce it to a number. Then soon enough evidence was generated that some races, or social classes, or groups of people, did better on intelligence tests than others, again leading to notions of superiority and inferiority. The eugenics movement arose in the early twentieth century advocating the betterment of the intellectual level of society. In the United States, terms like “feeble-minded” and “moron” were developed to denote people who scored poorly on intelligence tests. The eugenics craze in the United States led to restrictions on immigration and forced sterilizations of tens of thousands of people, which invariably affected to a greater extent those who were poor, uneducated, and from minority groups. All these terrible ideas are discredited nowadays, at least academically, but watered down versions of these ideas still linger among the general public and some scholars. Asking questions about what made Einstein extremely intelligent are legitimate. But my fear is that if we do discover some characteristic in the brain responsible for genius, let’s call it “X”, we will again travel down this well-worn step by step path: 1) “X” made Einstein a genius. 2) Therefore, the more of “X” you have, the more intelligent you are. 3) We can classify otherwise normal individuals into whether they are more or less intelligent based of the amount of “X” they have. 4) Groups of people displaying lower levels of “X” are dumber. 5) Groups of people displaying lower levels of “X” are inferior. 6) Allowing these groups of people with less “X” to breed or to come to our country will compromise our society. 7) We must do something about it. A while ago I did something that Einstein would have disapproved of. I went to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. As part of what they call “Brain Awareness Week” they had an exhibition on Einstein’s Brain. The museum has a set of slides made from Einstein’s brain that Harvey’s estate donated after Harvey died, and some of them were on exhibit. So I took a picture (see below). This section of Einstein’s brain was stained for myelin, the protein that ensheaths the axons of neurons. The black area is the fiber tracks (the white matter in the brain), and the brown area is where the neuronal cell bodies reside (grey matter). There is (or was) something in sections like these that made possible the thinking of ideas that no one had ever thought before, revolutionizing our view of reality, and changing our world forever. What is or was that something? And if we ever discover it, what will we do with that knowledge? The photograph of Albert Einstein by Orren Jack Turner obtained from the Library of Congress is in the public domain. The image of Einstein’s brain was cropped and modified from the article: Falk, Dean, Frederick E. Lepore, and Adrianne Noe. "The cerebral cortex of Albert Einstein: a description and preliminary analysis of unpublished photographs." Brain 136.4 (2012): 1304-1327, and is used here under a NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) license. The image of the section of Einstein’s brain is by the author and can only be used with permission. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed