|

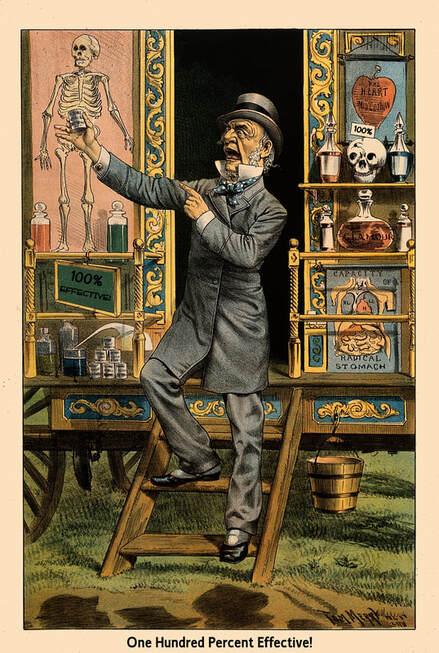

I had an exchange on Twitter with people alleging that doctors are finding that the drug hydroxychloroquine is 100% effective against COVID-19 and posting videos of patients claiming they had been cured by this drug. I tried to explain that this evidence is not valid and provided a link to one of my previous posts that addressed these claims. Then I stated that we need to wait for the results of the clinical trials. The response I got was that if doctors and their patients have tried it and are convinced it works, then that’s all the evidence we need. Unfortunately, this is simply not true. Even before hydroxychloroquine came along, the majority of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 would survive. If all patients are treated with hydroxychloroquine, then how do we know which patients got better because of the drug and which got better because they were going to get better anyway, or because of other treatments? In an uncontrolled clinical environment in the middle of a pandemic, patients are not randomized into matched groups and their treatments controlled and blinded to exclude placebo effects and other biases. Patient testimonials and doctor’s opinions are valuable to design clinical trials, but they have many shortcomings and should never be used to establish whether a drug works or not. All doctors know (or should know) this. However, the main point of this post is not to address the claim that hydroxychloroquine is 100% effective against COVID-19, but rather the attitude of scientists towards such claims, especially when they are reported using the media instead of the regular scientific channels. Scientists know that products or therapies that are 100% effective are rare, and this is even more so in the case of major diseases like COVID-19. Some vaccines, hormones like insulin, or a few antibiotics have approached this level of effectiveness, but this is not very common for most other compounds or drugs. About 86% of the drugs tested in clinical trials are found not to be effective and are not approved. Claims of 100% efficacy for a drug or therapy will trigger a strong (and warranted) skeptical response from most scientists.  Quack Quack I have been around a while, and I have read many investigations into multiple bogus claims regarding miracle cures or procedures promoted by quacks. One of the characteristics of these individuals is that they inflate the claims they make regarding the efficacy of their products or therapies beyond the bounds of credibility. If these fraudsters wanted to be believable, they would probably look up the percentage cure rate of the best science-sanctioned therapy and then inflate the claims for their products or therapies by a few percentage points to make them look significantly better but not impossibly so. However, the target audience of these individuals is not scientists but the general public, which has no experience with scientific research or clinical trials and their nuances. As I have explained before, the best way to promote a bogus product or therapy is to make your audience assimilate your product as part of their identity. If you can achieve this, your audience will be impervious to evidence that the product does not work. This is because any attack on your product will be viewed by the members of your audience as a personal attack on themselves. From this vantage point, it is unfortunate that the president of the United States has promoted the use of hydroxychloroquine. In the current politically charged atmosphere, I am concerned that this identity-forming process seems to be coalescing around the notion that if you don’t accept that hydroxychloroquine works, then you are against the president and thus part of a left-wing conspiracy. It is then all too easy for unscrupulous individuals to exploit this situation by linking themselves to the “pro-president” audience and peddle hydroxychloroquine or other as yet unproven drugs or therapies for COVID-19. If their claims are questioned, all they have to do is argue they are being attacked by the same system that their audience believes is against them and the president. I was skeptical about hydroxychloroquine from the beginning, not because the president promoted it, but because the data for its effectiveness was weak. Thus when I hear these claims for 100% effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine (or any other drug or therapy for that matter), this immediately raises a red flag, and I close my mind to them. This may not seem the scientific thing to do, but remember that keeping your mind too open can be dangerous. As far as I’m concerned, like the late astronomer Carl Sagan said, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”, and the burden of proof is on those individuals who make these claims. It is up to them to produce high-quality evidence to support that what they claim is true, and, seriously, with a 100% success rate this should not prove too difficult, right? At this point you may argue that even if the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine is less than 100%, but something like 80%, or 50% or 30%, that would still be significant and important. My answer to this is, yes, but this HAS to be established by well-designed clinical trials. At the moment, many clinical trials of hydroxychloroquine are ongoing, and several of these trials are sufficiently well-designed to yield unambiguous results. As I write this, among the best trials completed so far, one has indicated that hydroxychloroquine does not work as a prophylactic against COVID-19, and another has indicated that hydroxychloroquine does not reduce the risk of death among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. The FDA recently revoked its emergency use authorization of hydroxychloroquine, because based on the available evidence it’s unlikely to be effective in treating COVID-19 and any potential benefit from its use outweighs the potential risks. Many of these trials were designed to address the initial claims for hydroxychloroquine being very effective when administered alone or with certain antibiotics. A new claim has been made that hydroxychloroquine is only effective when it is administered with zinc, and new clinical trials are being performed to evaluate this possibility. As I stated above, I am skeptical about hydroxychloroquine, but I don’t want to be right, I want to save lives, and I hope the combination of hydroxychloroquine with zinc works. However, the public has to understand and accept the need to perform clinical trials and stop relying on testimonials and other anecdotal evidence. Image of a quack doctor selling remedies from his caravan; satirizing Gladstone's advocacy of the Home Rule Bill in Parliament is a Chromolithograph by T. Merry, 1889, and comes from the Welcome Collection. The image was modified and used here under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license, and no endorsement by the licensor is implied.

0 Comments

In this post we are going to go over the several razors available for us to use. These razors, while commonly used by philosophers and scientists, in fact are often used by regular people, sometimes without even knowing that they are using them! However, these razors have nothing to do with the removal of bodily hair. They are called razors because they allow us to deal with the complexity of the world around us by reducing (cutting) the amount of possible explanations to various phenomena. We use them to simplify our thought processes and focus on meaningful explanations without getting lost in a bog of deceiving alternatives. We will examine several of these razors and see how they can be used to deal with the amount of bilge that is often found among claims of conspiracy theories, the pseudosciences, and the paranormal. 1) Occam’s Razor. This is the most well-known of all razors. It was developed by the English philosopher William of Ockham back in the fourteenth century. This razor posits that when faced with choosing between two competing alternatives that explain a phenomenon, we should choose the simplest one. In other words, we should not make things needlessly complicated. Many conspiracy theories such as those which claim that 9/11 was a US government-supported operation or that the US never landed on the moon run afoul of this razor. The sheer number of moving parts that would have to operate just right under a mantle of secrecy to bring about the events alleged in these conspiracies is just too complicated. The simpler explanation is that there was no conspiracy.

2) Hitchens's Razor. The late author, critic, and journalist Christopher Hitchens promulgated the dictum which states that what can be asserted without evidence, can be dismissed without evidence. The implication of this razor is that the burden of proof of a claim is with the claimant. You often hear many proponents of the occurrence of paranormal events declare that these phenomena have not been disproven. By this razor’s criteria, this argument is irrelevant. If you want people to accept a claim, YOU have to prove it is true, and you had better do a very damn good job at it to be taken seriously. 3) Sagan’s Standard. The late astronomer Carl Sagan popularized this aphorism which postulates that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. This standard recognizes that not all claims are created equal. Fantastical claims which run counter to scientific laws or mountains of evidence should only be accepted upon the production of truly remarkable evidence. By the metrics of this razor, claims for psychic phenomena, faith healers, and other such things fall short of the level of proof required to accept them. 4) Alder’s Razor. The Australian mathematician Mike Alder published an essay describing this razor, although at the time he called it “Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword” (which is a cooler name). The brutal postulate of this razor (or sword) states that what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating. If you have ever had an exchange with a flat Earth proponent and regretted afterwards having lost one hour of your life, you have experienced in the flesh what Alder was talking about. 5) Popper’s Falsifiability Principle. The great philosopher of science Karl Popper coined this famous principle which states that for something to be considered scientific it must be falsifiable. What this means is that there must be a way of proving that a claim is false if it indeed is false, otherwise said claim is not scientific. And if a claim is not scientific, its truthfulness will never be settled by observation or experiment (see Alder’s Razor above). A classical feature of the thinking of those making fantastical claims is that they always move the goalposts. No possible observation or experimental result can prove them wrong. Therefore they can’t be right. On the other hand, science can be right because it can be wrong. 6) Hanlon’s Razor. This particular razor of uncertain origin deals with the motivations behind those who propose fantastical claims. It states that one should never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. While it is true that within the ranks of those who believe in and peddle fantastical claims there are many liars and cheats, this razor reminds us that there are also scores of honest individuals who are just guilty of self-delusion or who have been bamboozled into accepting and defending these claims. In a recent post I reminded my readers about the dangers of keeping one’s mind too open (i.e. it can easily be filled with trash). Well, I guarantee that if you put these razors between you and the vast vortices of irrationality and trickery that swirl about us, your mind will be spared! The image is by Horst.Burkhardt is used here under an Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed