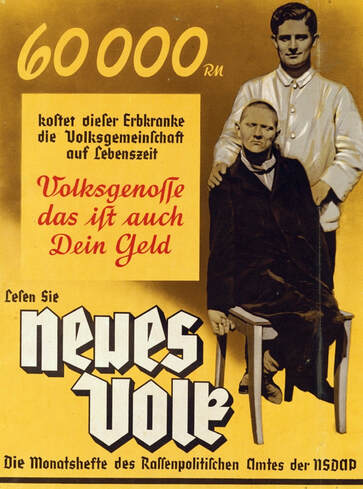

People think about intelligence based on its association with the extremes. On one side there are individuals who achieved fame for excelling in their fields. So clearly Nobel Prize winners like Albert Einstein or millionaires like Warren Buffett are very intelligent. These are the geniuses. At the other end of the scale, there are individuals who struggle with the intellectual challenges of everyday life. These people (in these enlightened times) are said to have “intellectual disabilities”. And in between these extremes you find people who are able to function normally and excel to a lesser or greater extent in their communities, their work, and their social life. These are people like you and me: the average folk. To most people, it seems obvious that there is a significant difference in intelligence between the average folk and the geniuses, or between the average folk and those with intellectual disabilities. It also seems equally obvious that these differences have real-world consequences. These are notions that most people accept. What is unwarranted, however, is the next level in this sequence of reasoning. This is the notion that, just as there are significant differences in intelligence between the extremes and the middle that have real-world consequences, there also are differences in intelligence among average folk that are significant and have similar consequences. If this were just merely a notion, there would not be an issue, but because intelligence is what makes us unique among all living things, we are fascinated by it. We want to know what it is. We want to define it. We want to grasp it. We want to dissect it. We want to measure it. We want to reproduce it. In order to do this, we have to assume that intelligence is something tangible that can be defined, grasped, and measured. Through several iterations in our attempts to quantitate intelligence (that have included the likes of follies such as cranial capacity) we have arrived at the notion that intelligence is the ability to solve problems, and therefore that intelligence can be “measured” by how well a person performs in solving a series of problems presented to them: the so-called intelligence tests. These tests were originally conceived to identify students who required extra help in school environments, not to ask how intelligent these children were. The tests were also used to gauge whether therapies or interventions were being successful at improving the students’ conditions. However, soon versions of these tests began to be applied to adults and otherwise normal individuals, and were used to produce a single number which would rank people from least to more intelligent. Here is where the problems arise. The general public has to understand that intelligence tests have two serious limitations when it comes to the assessment of intelligence. One limitation of these tests is that they are not useful for assessing differences among otherwise normal individuals or groups of normal individuals. A large difference in intelligence test scores between a genius and an average person has an obvious interpretation (the genius is more intelligent), but a smaller difference in intelligence test scores among average individuals cannot be interpreted so readily in terms of their real-world impact. It has been found, for example, that among people with equal levels of education, the performance in intelligence tests is a poor predictor of job performance, occupational standing, earnings, or wealth. Nevertheless, it is telling that we often associate being intelligent with being famous, amassing a fortune, or winning a Nobel Prize. However, what about being a moral and ethical individual, being a good parent, being active in the community, being a good friend, organizing for social action, etc.? A person who excels in these activities may not be labeled a genius or become rich or famous, but can anyone seriously argue that having the intellect to be successful in these activities does not require a substantial amount of intelligence? This issue leads us to the second and most serious limitation of intelligence tests, namely the fact that they only assess a limited aspect of what we call intelligence. There is strong evidence that human intelligence is not one thing, but rather that it is made up of several independent components which are in turn associated with multiple brain operational networks. This means that intelligence is an emergent property of several human abilities, and it cannot be reduced to a single number that measures how intelligent someone is. For example, someone can be very intelligent and use this intelligence to figure out how to rob a bank, make an illegal drug, or kill a person. However, many would argue that doing these things is very unwise. Shouldn’t wisdom be considered part of intelligence? Another example is sociability. What about people that know how to fit in and get along with others? What about people who know what to say, when to say it, where to say it, how to say it, and whom to say it to? There are very smart individuals that are socially awkward or disdainful of others they regard as inferior and unable to fit within a social structure or work in a team. Should sociability be considered part of intelligence? The representation of a person’s intelligence that we obtain from intelligence tests is at best incomplete and at worse biased. In fact some researchers in the area of intelligence think that the only thing intelligence tests evaluate is how well you perform at taking intelligence tests!  Nazi poster highlighting the high cost of caring for people with hereditary illness Nazi poster highlighting the high cost of caring for people with hereditary illness Because intelligence is so central to the human species and because of the notions that most people harbor about intelligence, the potential for the misuse of intelligence test results is great. Very few people would argue that it is not desirable to be more intelligent, and there is a stigma associated with being in the low end of the intelligence spectrum. Remember that individuals with intellectual disabilities were once formally referred to as “idiots”, “imbeciles”, or “morons”. Most people consider the opposite of intelligent to be “dumb”. These people also believe that “less intelligent” is synonymous with “dumber”. When groups of people are found by intelligence tests to score lower than other groups, in the eyes of many the lower scores implies “dumber”. Once that step is taken, the transition from “dumber” to “inferior” is all too easy and common. And from here, the dark and twisted history of our efforts to assess intelligence has produced abominations ranging from forced sterilization of individuals and restrictions in immigration in countries like the United States, to outright killing of those judged to be feeble minded in places like Nazi Germany. Even today, intelligence testing differences among races are being used to argue for the intellectual superiority of one race over others. Research into the nature of intelligence is a valid scientific endeavor, and the restricted application of intelligence tests to very specific situations can be beneficial. But expanding the application of intelligence tests to otherwise normal individuals coupled with inaccurate notions harbored by the general public regarding how these tests work and what they mean, can fuel discrimination and racism. It has happened in the past and it can happen again. The brain image from Pixabay is free for commercial use. The Nazi poster by the Neues Volk ("New People") magazine published by the Rassepolitischen Amt der NSDAP (Office of Racial Policy of the Nazi Party) around 1937 is in the public domain.

0 Comments

|

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed