|

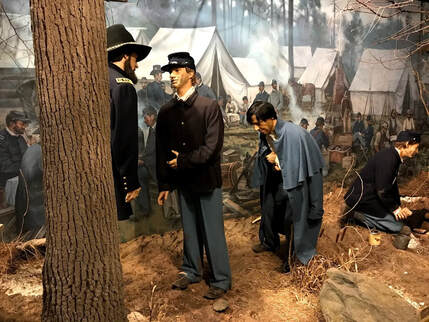

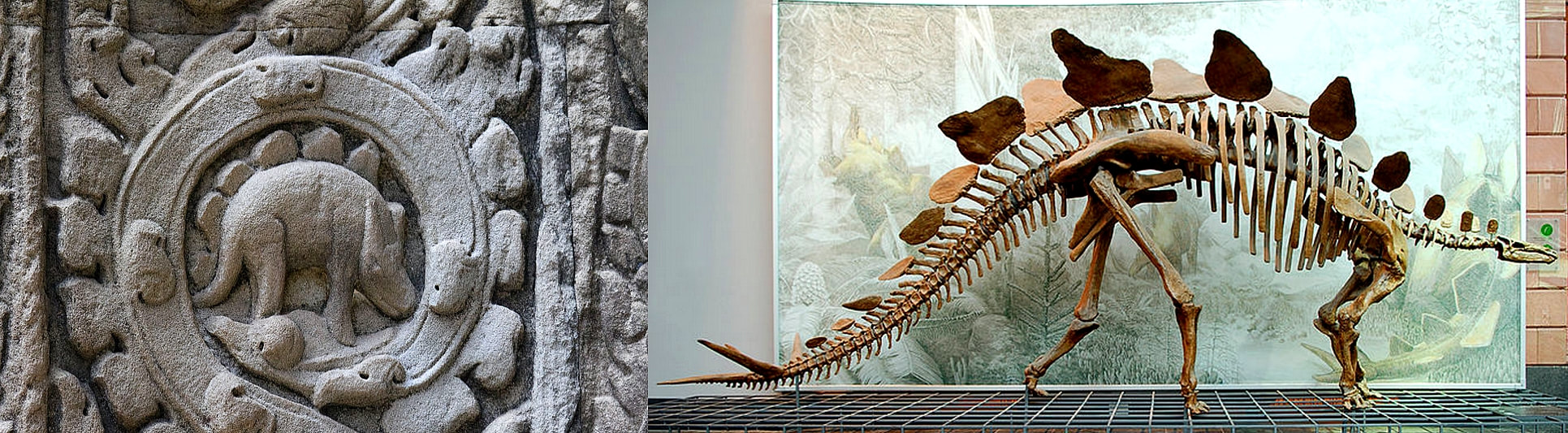

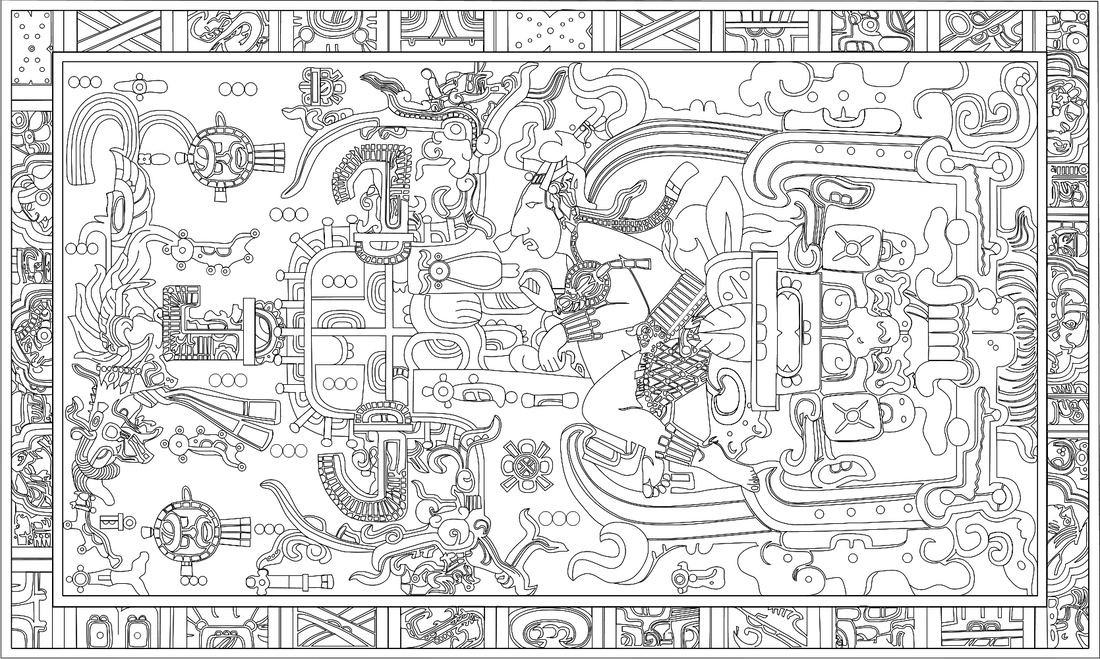

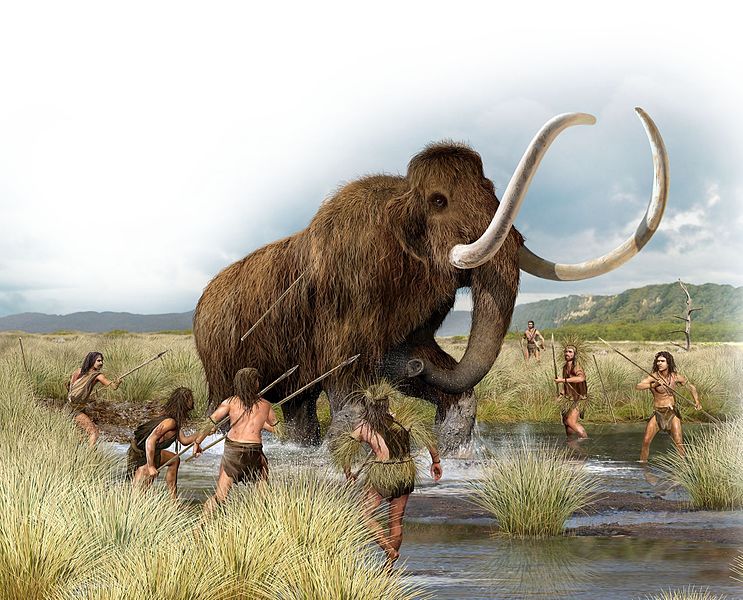

One of the many claims of creationists is that human beings coexisted with dinosaurs, but the fossil record does not back this claim. Dinosaurs became extinct around 65 million years ago, whereas the oldest modern human fossils are less than a million years old. So how do creationists reply to this? Creationists have pointed to alleged evidence which suggested that human and dinosaurs were contemporaries such as fossil footprints of human and dinosaurs found side by side. However, this evidence has turned up to be either the result of misinterpretations or hoaxes. Never to be discouraged by negative evidence, creationists have turned to another source of evidence: art! Ancient humans throughout the world have left a large number of inscriptions, paintings, sculptures, and other forms of art in their caves, dwellings, and artifacts such as pottery. In these, ancient humans depicted some of the animals that were in their vicinity and which they often hunted. The idea is that, if humans and dinosaurs were living side by side, dinosaurs would be represented in ancient art. Is this the case? Creationists claim that this is indeed the case, and they point to many examples of ancient art throughout the world that seem to show large animals that in some cases bear resemblance to dinosaurs. Unfortunately there are many problems with this claim. To begin with, some of these pieces of ancient art have been exposed as hoaxes. Among these are the Ica Stones and the Acambaro Figurines that depict dinosaurs or humans interacting with dinosaurs. Other instances of ancient art that were claimed to be dinosaurs, such as those at the Kachina Bridge site and at various other sites, have been reinterpreted as symbolizing other animals or mythical creatures, or to be the product of the blending of several weathered figures plus mud or mineral stains. Finally, other claims that paintings or figures of dragons represent dinosaurs are clearly a stretch of the imagination. There are some genuine depictions of animals in ancient art that bear a resemblance to dinosaurs. One of the most famous is a carving in the Temple Ta Prohm in Cambodia, which looks like a dinosaur called a stegosaurus. However upon careful analysis, this resemblance turns out to be superficial. For example, the spikes in the tail are missing, the proportion of the head to the rest of the body is all wrong, and the carving seems to show the presence of horns or ears in the animal’s head which do not occur in stegosaurs. Skeptics believe that this carving represents another animal such as a rhinoceros, and that the alleged plates on its back, which are found in other carvings in the same temple, may represent leaves. This disagreement exposes the central problem of taking ancient art as proof for the existence of something: interpretation. Even in these modern times of science, technology, and urbanization, human populations develop a cultural mythology that gives rise to fantastic beliefs in notions, characters, or entities that often end up being represented in art. This process has been probably taking place since the dawn of humanity. Even when we see an ancient carving, painting, or sculpture that bears an unambiguous resemblance to something modern, how do we know that the resemblance is not a coincidence? How do we know that what the author actually saw is what he or she depicted in the art as opposed to it being a representation of a dream, a belief, an embellished story, or something that was misperceived? To show you how problematic the interpretation of ancient art is, let me tell you about ancient astronauts. There is a group of people that claims that ancient art shows that primitive cultures had contacts with ancient astronauts and their machines. They point out to art all over the world that seems to depict images that bear resemblance to people wearing helmets and different types of crafts. For example, the lid of the tomb of the Maya ruler Pacal the Great depicts a human figure manipulating the controls of what seems to be a space vessel which even has flames coming out of one end. Egyptian hieroglyphics from the temple of Seti I at Abydos contain images of what appear to be a helicopter and other types of modern looking crafts. Petroglyphs from the Camonica Valley in Italy seem to depict figures wearing helmets. This post is not the place to deal with these claims, but let me just mention that they are all based on misinterpretations of what these figures represent. Ironically, some creationists have been among the most vocal critics of ancient astronaut proponents. However, how is using ancient art to argue for the existence of ancient astronauts different from the argument championed by creationists that humans coexisted with dinosaurs? How do we tell what is real? The answer is we can’t. Ancient art alone cannot be taken as proof of the existence of the entities represented in the art. Additional evidence is required. Consider the case of mammoths. There are hundreds of representations of mammoths in cave and other forms of art in areas of Europe and Russia, but there is also abundant evidence that ancient humans hunted mammoths or scavenged their corpses for food, and used their tusks to construct dwellings, to produce tools, and to carve and make art. The dating of mammoth and human remains and tools found in these areas also show a degree of overlap in the geological age indicating that these two species were contemporaneous. Why is there no such evidence for dinosaurs and humans? Creationists often complain that scientists are biased against their ideas, but how do they expect to be taken seriously when they demand that science upend well-established scientific theories backed by vast amounts of solid evidence based solely on a few carved or painted figures? We might as well accept that ancient astronauts visited the Earth! Photograph of Ica Stone Brattarb used here under an Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Photograph of Acambaro figurines by Fchavez2000 is used here under a GNU Free Documentation License, version 1.2. A drawing of the lid of the tomb of Maya ruler Pacal the Great by Madman2001 is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license. Image of the so called helicopter hieroglyphs by Olek95 are in the public domain. Photograph of petroglyphs in Italy by Luca Giarelli used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license. Image of alleged stegosaur carving at Ta Prohm Temple by Harald Hoyer is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license. Photograph of a cast of a Stegosaurus stenops skeleton (AMNH 650) in the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt am Main by Evak is used here under a GNU Free Documentation License, version 1.2. Mammoth hunt image used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.

2 Comments

There are certain sayings “out there” that are repeated over and over by those who want to delegitimize science and support pseudoscience and fantastical claims. One saying that you often hear is, “Science can’t prove a negative”. What is meant by this? A “negative” is a claim expressed in negative form. So “ghosts exist” is the positive form of a claim whereas “ghosts do not exist” is the negative form of the claim. It is argued that the positive claim “ghosts exist” is provable, because all you have to do is demonstrate the existence of at least one ghost for it to be true. However, it is maintained that the claim “ghosts do not exist” is unprovable because no matter how many times you investigate the existence of an alleged ghost and come up empty handed, you will never exclude the possibility that there is a ghost somewhere.  Historical marker commemorating the Michelson-Morley experiment. Historical marker commemorating the Michelson-Morley experiment. However, science proves negatives all the time. The key to doing this is defining the characteristics of whatever it is we wish to find, and, if applicable, circumscribe its presence in space and time. Defining the characteristics of what we wish to investigate allows us to come up with a method of detection. Stating where and when what we wish to investigate should be, allows us to perform the detection at the right place and time. If we then proceed to perform the detection at the stated place and time and we find nothing, we can conclude that an entity with the specified characteristics that we looked for at the stated place and time doesn’t exist, because if it existed, we would have detected it. A famous example of this is the so called Michelson-Morley experiment. When it was determined that light had the characteristics of a wave, the question arose as to through which medium light traveled. Sound waves travel through solids, liquids, and gases as compression waves, so light was proposed to travel forming waves in a medium that was called “aether”. Two American scientists, Albert Michelson and Edward Morley, worked out how light would interact with this alleged “aether” and performed several experiments in 1887 to measure this interaction. The overall conclusion of these experiments was that the “aether” did not exist, and similar experiments conducted since then with ever increasing precision have confirmed the results. The above procedure can also be applied to things like claims for the existence of ghosts. Of course, if the proponents of the existence of ghosts and other paranormal occurrences cannot define the characteristic of the phenomena whose existence they advocate or when and where they occur with any degree of certainty, then there are serious concerns regarding whether these claims have any merits from a scientific point of view. We might as well discuss how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Here we are better served by applying Alder’s Razor (what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating). Another saying related to the one we dealt with above that is often encountered is that “The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. What is meant by this is that no matter how many times we perform tests or make observations to ascertain the existence of something such as, for example, a medical effect, if we find no evidence of its existence, we cannot conclude that it doesn’t exist. This argument is frequently made by those who advocate products and treatments of dubious value or those who are hell-bent on defending disproven propositions. The idea is that no matter how much evidence to the contrary, there MAY BE an effect that the studies may have missed. The problem with this thinking is that a carefully designed series of robust studies can be carried out to evaluate the existence of an effect of a certain magnitude. The point is not whether there is a very small effect. The point is whether there is an effect of practical importance.

For example, many people were concerned that the vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) caused autism. In response to this, scientists carried out several studies evaluating possible risks of autism as a result of vaccines which all in all included hundreds of thousands of children. No significant association between autism and this vaccine was found. Could there nevertheless be a very small effect that was not detected by the studies? Yes, but such an effect would be so small as to be of no practical importance, especially compared to the risks of unvaccinated children contracting measles, mumps, and rubella. One final saying that pops up among the pseudoscience crowd is that concerning products or therapies that have not yet been investigated. When unresearched products or therapies used by people come under criticism, their proponents argue that, “There is no evidence that they don’t work.” Thus what they are saying is that, because it has not been found to be ineffective, it is OK to keep on using it, even though this argument should cut both ways (if there is no evidence it works you should not use it). This line of reasoning essentially argues that ignorance is a valid reason to justify using a product or therapy. It treats ignorance as evidence! Even if the effectiveness of a particular product or therapy has not been investigated, there may be grounds for serious skepticism regarding its use based on other considerations. For example, if a new untested homeopathic product is introduced into the market, we would be justified in being skeptical regarding its effectiveness because the principles on which homeopathy is claimed to work violate well-established chemical laws. Additionally, the best designed studies assessing the effectiveness of existing homeopathic products have yielded negative results, so a new product will not fare any better. So to recap, science CAN prove a negative, absence of evidence CAN be evidence of absence, and ignorance IS NOT evidence. Photo of the plaque commemorating the Michelson-Morley experiment by Alan Migdall is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0). I was going over some statistics regarding US wars, and something caught my attention. During the Civil War the Union Army (for which the statistics are more accurate than for the Confederate Army) suffered a total of 364, 511 casualties between 1861 and 1865. Of these casualties only 140,414 (39%) were battle deaths with the rest (224,097; 61%) being due to “other causes”. In contrast, during the war engagement known as Operation Iraqi Freedom, which took place between 2003 and 2011, US forces had a total of 4,419 deaths of which 3,481 (79%) were combat deaths and 938 (21%) were non-hostile. What was the difference between the Civil War and Operation Iraqi Freedom 140 years later that led to a much lower proportion of non-combat related deaths? To find out, I went to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. There I learned a surprising fact. Of the nearly 620,000 soldiers (both Union and Confederate) who died during the Civil War, two-thirds died from disease!  Crowded living conditions in Civil War military camps. Crowded living conditions in Civil War military camps. Many new army recruits had never lived in densely populated areas and therefore had never been exposed to diseases such as mumps, measles, or chicken pox. Many soldiers contracted these diseases as a result of large numbers of men living in crowded spaces. To make matters worse, the environment of the military camps was often unsanitary as a result of human and animal excrement contaminating the water supply and breeding flies, lice, and fleas which were vectors of bacterial and viral diseases. In addition to this, the food consumed by the soldiers was often of poor nutritional value causing scurvy (vitamin C deficiency), night blindness (vitamin A deficiency) and malnutrition. All of the above was of course superimposed on the arduous strain of military life, and during the first months of service as many as half of the recruits were incapacitated by sickness. Among the deadly and incapacitating diseases afflicting the armies fighting the Civil war were diarrhea and dysentery, malaria, measles, sexually transmitted diseases (mostly syphilis and gonorrhea), typhoid fever, yellow fever, tuberculosis and scrofula, and a form of rheumatism that is now called reactive rheumatism which caused severe swelling of the joints. Tens of thousands of soldiers from both armies were discharged as a result of disease. While there were treatments available such as quinine to treat malaria, opium and morphine to relieve pain, bromine to treat hospital gangrene, or quarantine to prevent spread of yellow fever, many treatments were palliative, ineffective, or even dangerous such as in the cases of medicines that contained mercury or arsenic. At the time of the Civil War, many chronic diseases were untreatable. For example, one third of the deaths in veteran’s homes after the war were due to late-stage venereal diseases.  Battlefield amputation during the Civil War. Battlefield amputation during the Civil War. Soldiers that survived sickness had to deal with the peril of being wounded in battle. At the time, the reason for infections and how they spread was not understood, so surgeons did not sterilize their instruments. About 3/4 of surgical interventions during the Civil War were amputations. Post-operative infections were common, and in this era before antibiotics nearly 30% of soldiers undergoing amputations died. Another dimension of the stresses to which Civil War soldiers were exposed was the psychological. The hardships of military life coupled with the horrors of the battlefield and the absence of loved ones took a toll on soldiers producing a type of homesickness that was called “nostalgia” or “melancholy”. This condition could lead to excessive drinking, depression, suicide, insanity, or desertion. After the war, many soldiers were affected by what was then called “irritable heart” and is now called “post-traumatic stress disorder” (PTSD). This made their return to civilian society after the war very difficult. Now fast forward 140 years. During this interval scientists figured out the role of germs in producing disease as well as the role of insects such as mosquitoes or fleas in transmitting them. Protocols for effective sanitation and disposal of waste and refuse were implemented. Antiseptic and sterilization techniques were developed. Antibiotics were discovered and mass produced. The underpinnings of the body’s immune response were elucidated and exploited to generate vaccines, and numerous other drugs were manufactured to treat specific ailments. The nutritional requirements of individuals were established as well as methods to prepare, store, preserve, and deliver nutritious foods free of contamination or spoilage. In the war environment various scientific advances have contributed to preserving the life of the soldier, ranging from body armor to sophisticated surgical techniques. The psychological effects of warfare are today recognized and the focus of active research with programs set in place to deal with PTSD. I went to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland, to look at an exhibit related to Operation Iraqi Freedom. In this museum they have an exhibit containing a 32 square feet concrete slab that formed part of the floor of Trauma Bay II which was the primary resuscitation bay in the Emergency Department of the U.S. Air Force Balad Theater Hospital in Iraq. This concrete slab is peppered with many marks and gouges and iodine stains that serve as a silent testament to the surgeons, physicians, and nurses that provided the best trauma care in the world to thousands of wounded individuals. What was the survival rate of American Soldiers and other individuals treated at Balad? It was an amazing 98%. The survival rates during Operation Iraqi Freedom are proof that medicine and other life-enhancing technologies have come a long way since the Civil War, and this all has been made possible by scientific discoveries in many areas and their application to solve specific problems. The photographs belong to the author and can only be used with permission.

Cryptozoology is a term invented by the late French-Belgian scientist Bernard Heuvelmans (who is known as the father of cryptozoology), and it literally means the study of hidden animals, or animals not yet known to science. This discipline in principle may not sound like anything controversial. After all, new species of living organisms are discovered all the time, and some of these have proven quite remarkable. The poster boy of cryptozoology is the coelacanth. The coelacanth is an ancient fish that was thought to have gone extinct about 66 million years ago and was only known from fossils, but the finding of a specimen of this fish off the coast of South Africa in 1938 caused a global sensation. Over the years more coelacanths have been caught and studied revealing amazing attributes of these fishes that are more closely related to mammals than to other fishes. Coelacanths have also been filmed in their native habitat. Cryptozoologists point to organisms like the coelacanth as proof that these hidden animals can exist and that there is the potential to discover new ones. However, cryptozoologists do not set off on expeditions to explore distant places or peruse the depth of the oceans to try to discover new organisms. Rather cryptozoologists examine legends, tales, and stories told by folks living in some regions as well as accounts by those who explored or travelled those areas to find evidence for the existence of undiscovered animals which they call “cryptids”. This is where the problem arises. Questioning indigenous populations can lead to the discovery of new species of animals. After all, many natives along the East Coast of Africa were well acquainted with the coelacanth which they would occasionally catch during their fishing activities. However, cryptozoologists tend to amass a large collection of anecdotal or indirect evidence that proves, at best, to be inconclusive, or at worst, to be of such dubious or fantastical nature that is seldom convincing to mainstream scientists. It doesn’t help that the standard-bearer of the cryptozoological community in the United States, the International Cryptozoology Museum in Portland, Maine (which features a coelacanth in its logo), has displays that range from the fake and bizarre to the downright ridiculous. Let’s take a look at some of the cryptids that cryptozoologist say are likely to exist based on their research.  Frame from Bigfoot Film Frame from Bigfoot Film Bigfoot or Sasquatch The stories and sightings of large ape-like hominids wandering the forests of California and other places in the United States go back more than 150 years. Cryptozoologists and other Bigfoot enthusiasts have cataloged eyewitness accounts of thousands of sightings of these creatures. There also are numerous alleged Bigfoot foot print casts, films, photographs, sound recordings, and even hair samples. Unfortunately, this body of evidence is problematic in many ways. Eyewitness accounts can be, of course, unreliable. The footprint casts do not display any consistent anatomical pattern. The recordings of alleged Bigfoot sounds have proven inconclusive. The analyses of purported Bigfoot biological samples have also proven inconclusive or have shown that the samples belonged to other animals. The most famous evidence for the existence of Bigfoot, a few seconds of film footage of an apelike creature walking in the forest shot in 1967 and known as the “Patterson Film”, has also proven very controversial with skeptics claiming that it is a hoax.  Loch Ness Monster Photo Loch Ness Monster Photo The Loch Ness Monster One of the most famous cryptids is the one that allegedly inhabits the Loch Ness Lake in Scotland dubbed the Loch Ness Monster by the media, but referred to more affectionally as “Nessie” by the locals and the Scottish tourist industry. There is a large collection of eyewitness accounts as well as photographs and several films that show something in the surface of the lake, but the possibility that these sightings may represent other animals makes this evidence inconclusive. The lake has been explored with both sonar and submarines, but nothing out of the ordinary has been found. The most famous photograph of the monster, the so-called “Surgeon’s Photo” by the English physician Robert Kenneth Wilson taken in 1934, has now been exposed as a hoax.  Yeti Footprint Yeti Footprint The Abominable Snowman (Yeti) Several European expeditions into the Himalayan Mountains reported the sighting of what looked like an anthropoid ape along with footprints of the animals that in the popular press of the times ended up being referred to as the abominable snowman or Yeti. Despite decades of search for such animals, nothing conclusive has turned up. Most scientists consider that the purported Yeti sightings and hair samples are those of bears. There are many other such proposed cryptids like the Latin American Chupacabra, the Australian Bunyip, the African Mokele-Mbembe, or the enigmatic Mothman in West Virginia, to name a few that have been claimed to exist, but again, no conclusive evidence has ever been produced to back these claims.

As in the case of the coelacanth, the only evidence that will convince scientists of the claims of the cryptozoologists is the finding of a specimen dead or alive of the creature they claim to exist. In most cases cryptozoologists claim that evidence for the occurrence of these cryptids goes back hundreds of years. This is only possible if there is a sizeable breeding population of these creatures. Because of this, one wonders why a specimen has indeed not turned up somewhere. Why is the evidence always indirect? When will cryptozoologists accept that the lack of evidence is evidence? The screen capture from the Patterson Film and the Surgeon Photo of the Loch Ness Monster are used here under the doctrine of Fair Use. The photograph of an alleged Yeti footprint by Gardner Soule is in the public domain and was modified from the original to eliminate text. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed