|

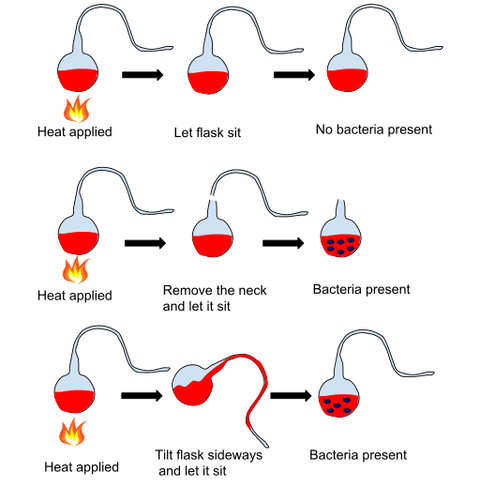

There is an old science joke where a scientist trains a spider to jump when a bell is rung. The scientist then removes a leg from the spider under anesthesia and makes sure the spider heals. The scientist proceeds to ring the bell again. Even with one less leg, the spider manages to jump in response to the sound. The scientist repeats this procedure removing a leg each time and ringing the bell, and the spider manages to “jump” in response (at least as best as it can). This goes on until the spider is legless. After repeatedly ringing the bell and getting no response, the scientist concludes that the spider without legs becomes deaf! What is ironic about this silly joke is that scientists have recently discovered that indeed the spider's ability to detect sound is based on hairs present on its legs. So you see, the scientist in the joke arrived at the right conclusion (legless spiders become deaf) although for the wrong reasons! The above got me thinking about whether there are any examples of real scientists who got it right but for the wrong reasons. As it turns out there are a several examples, and one of the most famous of these is the French Chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur and the idea of spontaneous generation. In the 19th century, the notion of spontaneous generation came under attack. This ancient notion posited that life continuously arises from non-life. At the time, the fact that nutrient broths exposed to the air would develop microorganisms was considered evidence for spontaneous generation. However, although a consensus had begun developing that life could only arise from preexisting life, and that the microorganisms that swarmed in nutrient broths represented nothing but airborne contamination, many scientists still defended the idea of spontaneous generation.  Into this scene entered Pasteur, and he performed his famous experiments where he boiled sugared yeast-water in a flask that remained exposed to the environment through a very long neck (swan-necked flasks). Pasteur found that the nutrient mix inside the flasks remained uncontaminated, presumably because any airborne organisms stuck to the neck of the flasks, but as soon as he broke the neck of the flasks or tilted them, bacteria and mold stated growing. He repeated these experiments with sterile liquids that did not have to be boiled, like blood or urine obtained directly from the bladder, and attained the same result. To great acclaim by the scientific community he declared that he had demonstrated that only germs in the air can produce the growth observed in these nutrient mixes, therefore life can only arise from life. However, a few scientists challenged Pasteur. These scientists, using different nutrient mixes like hay infusions or potash solutions derived from urine, found that microorganisms arose in nutrient broths even after they had been boiled and isolated from the environment in a manner similar to Pasteur’s procedure. They claimed their results proved that, at least in these different nutrient infusions, life arose by spontaneous generation and challenged Pasteur to repeat their experiments publicly. What did Pasteur do? He ignored their results, or dismissed them claiming they were due to sloppy methodology, and refused to repeat their experiments. Pasteur prevailed thanks to his connections, his fame, and for being against spontaneous generation at the right time. As far as he and his supporters were concerned the matter had been settled. So who was right? Even though Pasteur acted very unscientifically in addressing his critics, he was indeed right, but for the wrong reasons. Spontaneous generation does not occur, but Pasteur was wrong to ignore or dismiss his critics’ results, because these results were true. It would be more than a decade after Pasteur performed his experiments before it was understood that there are bacteria that produce spores which can survive heating at very high temperatures. It is likely that Pasteur’s infusions of sugared yeast-water did not contain these bacteria, but that the infusions of hay and potash employed by his critics had these spore-forming bacteria. Therefore, even after boiling these infusions at high temperature, Pasteur’s critics found these nutrient mixes became contaminated when the spores became active after the temperature had returned to normal. The critics were wrong in claiming their results supported spontaneous generation, but at the time the complete truth was not known, and there was enough ignorance to go around.  Pasteur Pasteur Ironically, if Pasteur had behaved like a true scientists and repeated his critic’s experiments, he would have had to face conflicting evidence that could have led him to admit that spontaneous generation was possible in some cases. This could have muddied up the field and hindered progress, but by ignoring valid data, he avoided an incorrect interpretation, and arrived at the right conclusion. Such is the complexity of the interaction between reality and the human mind in the context of scientific discovery. Pasteur moved on to greater accomplishments (and more controversy, but that’s another story) where he was proven right many times. Today he is remembered for the process to prevent bacterial growth in substances like wine and milk (pasteurization), his many contributions to the prevention of disease which saved countless lives, and the founding of the Pasteur Institute which over the years has had a huge impact on health science worldwide with 10 of its scientists being awarded Nobel Prizes. Nevertheless, in the case of spontaneous generation, he was right but for the wrong reasons! My reference for Pasteur’s story is John Waller’s excellent book: Fabulous Science. Image of Pasteur’s experiment by Kgerow16 is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license. The image of Pasteur by Paul Nadar is in the public domain.

0 Comments

|

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed