|

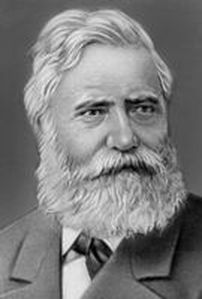

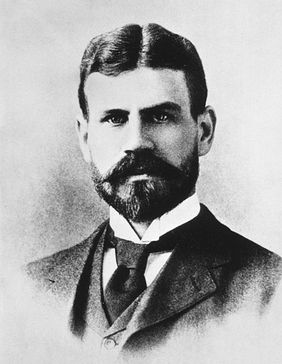

Most scientists have it easy. By this I don’t mean that science is easy, but rather that scientists experiment on animals or OTHER people. Sure, these experiments are conducted following ethical guidelines to minimize pain to laboratory animals or to ensure the safety of patients, but the point of my argument is that it’s easy to administer a treatment that makes the entity receiving said treatment sick, or that carries other risks, when that entity is not yourself. However, throughout the history of science some scientists have broken through the wall of security that separated them from their test subjects and became their own lab rats, their own patients. These scientists who experimented on themselves conducted what I call “heroic science”. Let’s look at some of these characters.  Barry Marshall Barry Marshall In a previous post, I mentioned the case of the Australian physician Dr. Barry Marshall who wanted to convince skeptical fellow scientists that ulcers were not caused by excessive stomach acid secretion due to stress, but rather by a bacteria called Helicobacter pylori. Unable to develop an animal model or to obtain funds to perform a human study, he experimented on himself by drinking a broth containing Helicobacter Pylori isolated from a patient who had developed severe gastritis. He developed the same symptoms as the patient and was able to cure himself with antibiotics. As a result of this and other studies, Dr. Marshall was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2005. Another of these heroic individuals was Werner Forssmann, who as a resident in cardiology in a German hospital wanted to try a procedure to insert a catheter through a vein all the way to the heart. Forssmann was convinced that if this could be done, it would allow doctors to diagnose and treat heart ailments. However, he could not obtain permission from his superiors to perform the experiment on a patient, so he tried it on himself. He made an incision in his arm, inserted a tube, and guiding himself with X-ray photography, he pushed the tube all the way to his heart. At the time there was a lot of opposition to Forssmann and his unorthodox methods, and although he persevered for some time, he became a pariah in the cardiology field and was forced to switch disciplines becoming a urologist. However, eventually other scientists refined the technique of catheterization described in his work, and developed it into valuable medical procedures that have saved many lives. Forssmann had the last laugh when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1956. Most heroic science studies didn’t lead to a Nobel Prize, but some resulted in useful information. For example, John Stapp was an air force officer who experimented on himself to test the limits of human endurance in acceleration and deceleration experiments. He would be strapped to a rocket that would rapidly accelerate to speeds of hundreds of miles per hour and then stop within seconds. As a result of these brutal experiments, Stapp suffered concussions and broke several bones, but he survived, and the knowledge generated by his research eventually resulted in technologies and guidelines that today protect both car drivers and airplane pilots. Despite its appearance of recklessness, heroic science is seldom performed in a vacuum, but rather it is performed by individuals who believe that, based on other evidence, nothing will happen to them.  Joseph Goldberger Joseph Goldberger Such was the case of Dr. Joseph Goldberger. In the early 1900s, the disease Pellagra afflicted tens of thousands of people in the United States. Dr. Joseph Goldberger performed experiments that indicated that Pellagra was a disease that arose due to a dietary deficiency rather than a germ. Faced with recalcitrant opposition to his ideas, Goldberger and his assistants injected themselves with blood from people afflicted with Pellagra and applied secretions from the patient’s noses and throats to their own. They also held “filth parties” where they swallowed capsules containing scabs obtained from the rashes that patients with Pellagra developed. None of them developed Pellagra. This along with other evidence demonstrated that Pellagra was not a disease carried by germs. Another case was that of the American surgeon Nicholas Senn, who in 1901 implanted under his skin a piece of cancerous tissue that he had just removed from a patient. As he expected, he never developed cancer. Senn did this to demonstrate that cancer is not produced by a microbe, as it is not transmissible from one human to another, although at the time there were many pieces of evidence that taken together indicated that this was the case. Of course, the mere fact that you perform heroic science doesn’t mean that you will reach the right conclusions.  Max von Pettenkofer Max von Pettenkofer Back in 1892 the German chemist Dr. Max von Pettenkofer disputed the theory that germs caused disease, and specifically that a bacterium called Vibrio cholerae caused the disease cholera. He requested a sample of cholera bacteria from one of the most prominent proponents of the theory, Dr. Robert Koch (who won the Nobel Prize in 1905), and when he got the sample he proceeded to ingest it! Pettenkofer fell slightly sick for a while, but did not develop cholera. He claimed that this proved his point, but the vast majority of the evidence generated by others indicated he was wrong, and his claim was never accepted. A rather remarkable example of misguided heroic science is the work of Doctor Stubbins Ffirth. This individual studied the incidence of Yellow Fever cases in the United States back in the 1700s and noticed that Yellow Fever was much more prevalent during the summer months. Thus he developed the notion that Yellow fever was due to the heat stress of the summer months, and that therefore it was not contagious. To prove this he embarked on a series of gross experiments where he exposed himself to the bodily fluids of Yellow Fever patients. He drank their vomit, he poured it in his eyes, he rubbed it into cuts he made in his arms, he breathed the fumes from the vomit, and he also smeared his body with urine, saliva, and blood of Yellow Fever patients. Since he never contracted the malady, he concluded that Yellow Fever was not contagious. However, not only did Ffirth employ bodily fluids from late-stage Yellow Fever patients whose disease we now know not to be contagious, but he also missed the fact that Yellow Fever is transmitted by mosquitoes (see below), which is the reason why it’s more prevalent during the summer! And finally, some of the scientists who engaged in heroic science suffered or died as a result of their experiments, but their sacrifice saved lives or resulted in advancements in the understanding of terrible diseases as the following two cases show.  Jesse Lazear Jesse Lazear In 1900 the army surgeon Walter Reed and his team in Cuba put to test the theory that Yellow fever was spread by mosquitoes, which at the time was not taken seriously by many scientists. They had mosquitoes feed on patients with Yellow Fever and then allowed the mosquitoes to bite several volunteers, among whom were two members of Reed’s team, the American physicians James Carroll and Jesse Lazear. Several of the people bitten by these mosquitoes developed Yellow Fever including Carroll and Lazear. Lazear died, but Carroll recovered, although he experienced ill health for the rest of his life. After this demonstration that Yellow Fever was transmitted by mosquitoes, a program of mosquito eradication was implemented that succeeded in dramatically reducing the cases of this disease. In the Andes in South America there is a disease called Oroya Fever that periodically decimated the population in some localities. In the 1800s many physicians suspected that this disease was connected to another condition that led to the production of skin warts (Peruvian Warts), but no one had ever demonstrated they were connected. Daniel Alcides Carrión, a student of medicine in the capital of Peru, Lima, set out to prove that these two diseases were the same. He removed a wart sample from a patient with the skin condition and inoculated himself with incisions that he made in his arms. Carrión developed the symptoms of Oroya Fever thus demonstrating that these two diseases were different stages of the same disease, which is now called Bartonellosis. Unfortunately, he died from the disease, but he is hailed as a hero in Peru.

The above are but a fraction of the cases of individuals who risked life and limb performing heroic science. Many people criticize the usefulness of most cases of heroic science, especially when it just involves a sample size of “one”, and these critics have a point. In the end, heroic science should be held up to the same standards of rigor as regular science. However, whether those that experimented on themselves did it out of need to overcome bureaucratic obstacles, the belief in the correctness of their ideas, scientific curiosity, or because they were crazy, you always have a certain degree of admiration for the individuals who put their lives and health on the line for a scientific idea. They are willing to cross a line of security that most researchers wouldn’t dare to cross. The Photograph of Barry Marshall by Barjammar is in the public domain. The photograph of Dr. Goldberger made for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain. The photograph of Max von Pettenkofer is in the public domain in the US. The photograph of Jesse Lazear from the United States National Library of Medicine is in the public domain.

0 Comments

In the excellent 1987 docudrama, Life Story, also known as The Race for the Double Helix, which dramatizes the discovery of DNA, Dr. Rosalind Franklin played by actress Juliet Stevenson complains to her colleague Dr.Vittorio Luzzati about leaving Paris to go to London to continue her work. “Why am I leaving Paris? She asks. Vittorio replies, “My dear Rosalind, you must turn your back on thoughts of pleasure. We are the monks of science.” To which Dr. Franklin adds, “And the nuns.” Vittorio’s comment was intended as a joke, but it did frame very well the attitude that scientists have had towards scientific work. Indeed at times the all-consuming devotion of scientists for their work has been reminiscent of a monastic class of individuals who make vows to eschew Earthly delights in favor of a chance to make scientific discoveries. This devotion and its associated work ethic were transmitted from one generation of scientists to another through teaching and example. I had a friend who, while pursuing his studies in medicine, had been accepted to carry out basic research once a week in the lab of a professor of certain renown. The first day he went to the lab he was pretty excited, and was thrilled that the professor stayed with him performing experiments until late at night. At the end of the workday the professor asked him, “At what time are you coming tomorrow?” Somewhat puzzled, my friend tried to explain that he could only come to the lab once a week. However, the professor would have none of it and insisted he come again next day. So my friend returned to the lab next day and he stayed until late again performing experiments with the professor after which the professor again asked him, “At what time are you coming tomorrow?” This went on for a week, and my friend was pretty wiped out, so he made it a point of explaining to the professor that this could not continue. He told him that not only did he have classes and patients to attend, but he also had a family. The professor was not impressed and replied, “When I was your age, I had a family, and I was in medical school too. I had to attend patients, I had to take classes; and I also had to pay my professors for teaching me”. Then he added, “I am not charging you anything. At what time are you coming tomorrow?”  These stories of sacrifice and devotion to scientific work were once very commonplace. I have known of scientists who worked so hard that they started sleeping in their labs because it made no sense to go back home at the end of the workday. I knew a scientist who one day arrived home just to find his infant daughter was speaking. He quizzed his spouse as to when this had happened, and she just replied, “While you were away in the lab.” He had missed her first words. I knew of a scientist who one day in the fall began a period of intense work and concentration in his research. He worked for months eating at his research institute’s cafeteria, and sleeping in the student lounge. After he achieved what he had set out to do, he decided to step out of the building for a change, and realized that it was spring. He had worked through winter! There were research institutes where working weekends and holidays was something that was (unofficially) “expected from you”. In these places, it was virtually impossible to have a chance at succeeding without devoting the extra time. As recently as 3 years ago, I was endorsing the application of a student to a research position, and as one of the plusses I said that if necessary he would come to work on weekends. There was a long silence on the other side of the phone, and then the person with whom I was speaking said in a sarcastic tone, “If necessary?” The sacrifice and devotion were not restricted merely to the amount of work that you would put into it, but also to the monetary compensation you received. I had a professor who often remarked how happy he was to be doing science, and how astonished he was that he was actually getting paid to do it. This attitude was very common in the older generations of scientists. Some of these scientists were scandalized when new generations of students started arguing that they had a right to be funded. When they were students, most of these older professors had been content just to have the honor to work alongside great scientists; salary was merely an afterthought. This mentality was so prevalent that it transcended into the broader society. I know of a colleague who once received a phone call from a human resources person to provide him information regarding a position to which he had been accepted at a company. However, he considered that the pay he was offered was too low and he tried to negotiate a higher salary. The human resources person was confused by this request and quizzically asked, “Why do you want a higher pay, aren’t you a scientist?”

The above are some of the myriads of stories out there of a culture that stressed scientific work above everything. The stereotype of scientists, according to this culture, are the individuals that work 80 hours a week and are happy to be doing what they like, regardless of the amount of salary they are receiving. I once even read an advice to young scientists stating that they should not get married too early in their careers because that would destroy their creativity! However, this culture is fading, and I think this is due to the confluence of several factors. 1) Nowadays there is an excess of scientists contending for an ever dwindling set of academic positions and resources. Competition for funding is fierce, and mere hard work and devotion to science is no guarantee of having your own lab and a successful career. 2) Many sources of employment outside academia have opened up for scientists, and it has become acceptable to have non-academic careers in science. At the turn of this century for a scientist to accept a job in industry was still referred to in some venues as “selling out”. This is not true anymore. Many scientists have flocked to occupations in industry, government, and other areas where they are able to earn decent wages and have a life. 3) Science used to be a male-dominated profession. It is easy for a man to “devote his life to science” if his wife can stay home and take care of the kids. In today’s world where both spouses work, this model is not feasible anymore. 4) Finally, I think that society has grown more cynical and selfish, and this is not necessarily all bad. If young individuals are contemplating devoting the best years of their lives to a given enterprise, they are asking more and more the question: what’s in it for me? The hallowed halls of science nowadays have fewer monks and nuns! The image is in the public domain |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed