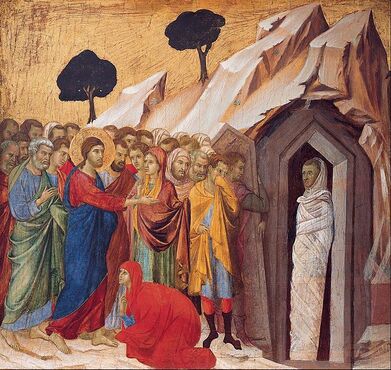

The Raising of Lazarus The Raising of Lazarus The drug hydroxychloroquine is being tested against COVID19, but there is still no compelling scientific evidence that it works, let alone that it is a “game changer” in our fight against COVID19. However, the president has claimed that there are very strong signs that it works on coronavirus, and the president’s economic adviser, Peter Navarro, has criticized the infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, for questioning alleged evidence hydroxychloroquine works on COVID19. The French researcher, Dr. Didier Raoult, who performed the original trial of hydroxychloroquine that generated all the current interest in the drug, now claims that he has treated 1,000 patients with COVID19 with a 99.3% success rate. In the news, I have read descriptions of patients that have recovered after being administered hydroxychloroquine in what has been called a “Lazarus effect” after the Biblical story where Jesus brought Lazarus back from the dead. So what is a scientist to make of this? I have acknowledged that science cannot operate in a vacuum. I recognize something that Dr. Fauci has also recognized, and that is that people need hope. However, as Dr. Fauci has also stated, scientists have the obligation to subject drugs to well-designed tests that will conclusively answer the question of whether a drug works or not. There seems to be a discrepancy between the quality of the evidence that scientists and non-scientist will accept to declare that a drug works, and there is the need to resolve this discrepancy. People anxiously waiting for evidence regarding whether hydroxychloroquine works, will understandably concentrate on patients that recover. Therefore they are more prone to make positive information the focus of their attention. Any remarkable cases where people recover (Lazarus effects) will invariably be pushed to the forefront of the news, and presented as evidence that the drug works wonders. What people need to understand, is that these “Lazarus” cases always occur, even in the absence of effective interventions. We all react to disease and drugs differently. Someone somewhere will always recover sooner and better than others. How do we know whether one of these Lazarus cases was a real effect of the drug or a happenstance? Isolated cases of patients who get better, no matter how spectacular, are meaningless. Scientists look at people who recover from an illness after being given a drug in the context of the whole population of patients treated with the drug to derive a proportion. The goal is then to compare this proportion to that of a population of patients not given the drug. Scientists also have to consider both positive and negative information. For the purposes of determining whether a drug works, patients that don’t recover are just as important to take into account as those that do. What if a drug benefits some patients to a great extent but kills others? Depending on the condition being treated, it may not be justified to use this drug until you can identify the characteristics of the patients that will be benefited by the drug. To do all the above properly, you need to carry out a clinical trial. No matter how desperate people are, and no matter how angry it makes them to hear otherwise, this is the only way to establish whether a drug works or not.  Hydroxychloroquine Hydroxychloroquine Once we accept the need for a clinical trial to establish whether a drug works, another issue is trial design. A trial carried out by scientists is not valid just because it happened. There are optimally-designed trials and suboptimal or poorly designed trials. There are several things a optimally designed trial must have. 1) The problem with much of the evidence regarding hydroxychloroquine is that it has been tested against COVID-19 in very small trials, and clinical trials of small size are notorious for giving inaccurate results. You need a large enough sample size to make sure your results are valid. 2) Another problem is: what you are comparing the drug against? Normally, you give the drug to a group of patients, and you compare the results to another group that simultaneously received an inert dummy pill (a placebo), or at least to a group of patients that received the best available care. This is what is called a control group. In many hydroxychloroquine trials there were no formal control groups, but rather the results were loosely compared to “historical controls”, in other words, to how well a group of patients given no drug fared in the past. But this procedure can be very inaccurate as there is considerable variation in such controls. 3) Another issue is the so called placebo effect. The psychology of patients knowing that they are being given a new potentially lifesaving drug is different from that of patients that are being treated with regular care. Just because of this, the patients being given the drug may experience an improvement (the so called placebo effect). To avoid this bias, the patients and even the attending physicians and nurses are often blinded as to the nature of the treatment in the best trials. Most hydroxychloroquine studies were not performed blind. 4) Even if you are comparing two groups, drug against placebo or best care, you need to allocate the patients to both groups in a random fashion to make sure that you do not end up with a mix of patients in a group that has some characteristic that is overrepresented compared to the other group, as this could influence the results of the trial. Most hydroxychloroquine studies were not randomized. These are but a few factors to consider when performing a trial to determine whether a drug works. These and other factors, if they are not carefully dealt with, can result in a trial yielding biased results that may over or underestimate the effectiveness of a drug. Due to budget constraints, urgency, or other reasons, scientists sometimes carry out very preliminary trials that are not optimal just to give a drug an initial “look see” or to gain experience with the administration of the drug in a clinical setting. But these trials are just that, preliminary, and there is no scientific justification to base any decision regarding the promotion of a drug based on this type of trials. The FDA recently has urged caution against the use of hydroxychloroquine outside the hospital setting due to reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with the drug. A recent study with US Veterans who were treated with hydroxychloroquine found a higher death rate among patients who were administered the drug (to be fair, this study was retrospective and therefore did not randomize the allocation of patients to treatments, so this could have biased the results). Even though I am skeptical about this drug, I would rather save lives than be right. I really hope it works, but the general public needs to understand that neither reported Lazarus effects nor suboptimal clinical trials will give us the truth. The 1310-11painting The Raising of Lazarus by Duccio di Buoninsegna is in the public domain. The image of hydroxychloroquine by Fvasconcellos is in the public domain.

0 Comments

For years those opposed to vaccination (antivaxxers) have peen plastering social media with their claims that vaccines are harmful, unnecessary, and ineffective. I had addressed the antivaxxer’s claims before, but I recently had a harsh exchange with some of these people on Twitter. These individuals bombarded me with links to articles and other evidence that “proved” their position was true. After I spent several days going over all this evidence, I found that the vast majority of it was nothing more than a mishmash of mediocre science, innuendo, exaggeration, distortion, and lies. So I organized all the evidence to address their claims. I started writing what I expected to be a two or three part blog post exposing the inaccuracy of the antivaxxer’s claims. However, besides getting me into another fight, I realized my effort wouldn’t really convince anyone that antivaxxers where wrong. I sensed the vaccine issue for most people hinged on more emotional rather than rational variables, and antivaxxers had proven particularly adept at stoking the fears of people and manipulating their emotions.  For years antivaxxers had thrived due to the fact that our society had become complacent. Today’ parents have never had to live with the horrors of smallpox, polio, diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, and other diseases. Even though antivaxxers are a minority, they were vocal and organized. They generated enough doubt in our society to give rise to vaccine hesitancy where parents delay or even refuse to administer some vaccines to their children. Predictably, some of the most contagious diseases like measles started coming back. A few antivaxxers thought that the possibility of a world without vaccines was within their reach, and they sought to articulate for others how that world would look. As it turns out, that was unnecessary. If anybody ever wondered how the world would look without vaccines, the COVID19 pandemic has made it abundantly clear how the world looks without ONE vaccine. As I write this, the worldwide confirmed cases of COVID19 exceed two million with more than 169,000 deaths, and more than 700,000 of those cases and 41,000 of those deaths are in the United States alone. Cities, states, and entire countries on lockdown, health care systems overwhelmed, and economies devastated. If anyone harbored any type of misgiving about the need for vaccines, that doubt has been vanquished. And COVID19 is not going to go away anytime soon. There are likely to be waves of the virus as a result of reintroduction when social distancing measures are eased. If sufficiently high numbers of people become infected and recover, a degree of what is called herd immunity may be able to protect those who have not been infected. However, only a vaccine will confer total immunity against the virus. There are currently around 41 research groups and companies in the race for a vaccine, and the hope is that one of these will prove sufficiently safe and effective to neutralize the COVID19 threat for the long-term.

Now that everyone has had a first-hand emotional experience of what a disease can do without a vaccine, I fully expect the antivaxxer influence to wane in our society. I am also planning not to write those blog posts rebutting the antivaxxer’s arguments, as they have become moot and are now a waste of my time. But there is one thing that I do have to point out, and that is the damage that antivaxxers have caused, but not just the one related to vaccine hesitancy or the wasting of resources investigating nonexistent connections between things like vaccination and autism. Vaccines are safe, but they are not risk-free. While being vaccinated is safer than risking having the disease, there are a very small percentage of individuals that will exhibit serious adverse side effects as a result of a vaccine. As vaccines are applied to hundreds of thousands, there will always be a chance that someone with an unknown susceptibility or condition will experience a serious reaction to a vaccine. Here is where antivaxxers could have made a difference for the greater good of society. They could have accepted the effectiveness and safety of vaccines and the need for them, while at the same time advocating for researching vaccine side effects and defining the characteristics of the susceptibility of individuals to developing adverse effects to vaccination. But instead of becoming advocates, they chose to become opponents. Antivaxxers sought out every possible side effect of a vaccine to paint it in the worst possible light. The interest that should exist in the side effects of vaccines has become linked to the antivaxxer position giving it a social stigma. Many people who accept the need for vaccines, but who are genuinely interested in studying and defining the side effects of vaccines, have found out to their chagrin that what they do is often associated with opposition to vaccination. How many people have antivaxxers impacted negatively by creating this stigma may never be known. It is unlikely however, that the antivaxxers will let up anytime soon. As the world anxiously awaits a COVID19 vaccine, antivaxxers may not have the influence that they once had. But if there is anything I have learned from arguing with climate change deniers, creationists, and proponents of 911 conspiracies, chemtrails, the flat Earth and other irrational skeptics is that they will move the goalposts. They will rationalize their failure, rework their arguments around any new evidence or situation, and fan new conspiracies. However, now that the sheer lunacy of the antivaxxer’s dream of a world without vaccines has been exposed, I am hopeful that society will not be as receptive to their arguments. The image by TheDigitalArtist from pixabay is free for public use. Although this is a science blog, I often address instances when belief clashes with science. I subscribe to the notion that religion and science have expertise over different areas and should be kept separate as per the concept of non-overlapping magisteria advocated by the late Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. But I recognize there will be cases where that separation becomes fuzzy or unworkable. I have made the point several times in my blog that science is the best method we have to discover the truth about the behavior of matter and energy in the world around us, and this is not an opinion. The success of science in discovering how the natural world works is plain for all but the most irrational skeptics to see. However, at the same time I accept that science cannot operate in a vacuum, and we have to contend with the reality of belief. In these trying times when we are in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, one of the crucial guidelines that scientists have issued to our population is the need for social distancing and avoiding crowds to reduce the spread of the virus. This guideline is derived from our knowledge of how the virus spreads. Because of this I was shocked when I saw the video below. This woman, who had just attended a church gathering where dozens of people hugged and assembled inside, has the firm conviction that the virus won’t infect her, and that she will not give it to others, because Jesus is protecting her. Most people will criticize the belief of this woman and her congregation and view them intellectually in unflattering terms. However, I understand the need that people have for religion, especially during trying times such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact this is nothing new. For millennia, human beings have invoked the deity to help them overcome challenges. I also understand that for many individuals, psychological well-being is often as important as physical well-being. This is not to say that all religious congregations have responded in the way this one did. The majority are offering virtual religious services and other activities that follow social distancing guidelines. But there are a substantial number that are still refusing, and these can (and have) become hot beds of virus spread. However, I don’t think this is solely a religious issue. In the United States, there is a distrust of government among many people. Any ordinance that in any way limits freedom is viewed with suspicion. If you include that there is the belief among some religious groups that a war is being waged on Christianity by atheists aligned with liberal organizations that wish to spread socialism and destroy the American way of life, you begin to get the idea of what may really be transpiring behind this opposition to common sense safety rules that interfere with regular worship. To this, of course, you must add the delegitimization of science that has taken place in our society, and the rise of antiscience movements such as those that advocate opposition to vaccination and climate change denial or the acceptance of conspiracy theories ranging from 911 and chemtrails to the flat Earth.  I believe, however, that there are ways to harmonize belief with science. If you look at the video of the woman again, you can see that she is wearing a seat belt. This makes sense, as science has generated evidence that seat belts along with air bags save lives during collisions. The woman probably doesn’t even think about this when she adjusts her seat belt upon entering the car. She also probably doesn’t even consider driving without a seat belt expecting Jesus to protect her in case of a crash. Additionally, the church she attends probably has lighting rods on top of the roof to protect the building and the people inside from lighting. It is likely that no one in the congregation has even considered removing the lightning rods and relying just on their faith in Jesus to protect the church. So there are clearly science-derived safety measures that these people accept. Why not then accept the safety measures against the coronavirus? While it’s true that, unlike the acceptance of seat belts or lighting rods, the social distancing guidelines impose a serious restriction in their ability to worship, in essence the occurrence of a viral pandemic is not different from a lighting strike: they are both natural phenomena. Car crashes are a more artificial situation, but they can be rationalized in terms of collisions among moving bodies (a physical phenomenon). If these people have accepted, or at least don’t question, the science and the necessity behind seat belts lighting rods and other such safety measures in their daily lives, how can we convince them that the safety measures against the virus are no different? As it turns out, many religious congregations, including some that share the same brand of Christianity as that of the woman in the video, have already taken care of this issue. They argue that God has responded to our prayers to keep us safe by giving us science, and through science we can understand how the world works and react accordingly. Viewed from this vantage point, applying our God-given science to come up with safety guidelines for the coronavirus is no different from applying it to come up with things like seat belts or lighting rods. No conspiracy. No attack on Christianity, No atheism or socialism. Science does not have an ideology. Science is a tool, and it the right hands it can be used for good. Of course, the above argument that God has given us science is a religious argument and therefore outside the scope of science. But if it means having people accept safety measures that will save lives, I am all for it. Rather than condemn and berate these people for their beliefs, I am of the opinion that the best way to proceed is to search for individuals whom these religious denominations will trust, and have them deliver this argument. Then it can be worked out how to adapt the coronavirus safety guidelines to meet the needs of these religious congregations. Image by geralt from pixabay is for public use.  Let’s face it. Most scientific articles aren’t funny. They are full of technical jargon, graphs, and tables, and to the average person they are downright boring. And even when scientists try to be funny or cute, the editors in the journals to which they submit their articles often request the removal of any such whimsy. However, a few scientists have achieved the feat of getting some whimsical things published. This is mostly seen in the titles of their articles. Today we are going to see a sampler of titles of some scientific articles that have broken the “boring barrier” in ways that range from the clever and naughty, to the insensitive and scatological. Prepare to be amused, amazed, and shocked by what these scientists got past the editors! Many witty titles of scientific articles are a play on words:

Fantastic yeasts and where to find them: the hidden diversity of dimorphic fungal pathogens by Caballero and coworkers, published in the journal, Current Opinion in Microbiology, in 2019. This is a play on words on the titles of a book and a film set in the Harry Potter Universe: Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find them. Dam nation: A geographic census of American dams and their large-scale hydrologic impacts by William Graf, published in the journal, Water Resources Research, in 1999. Dam nation/Damnation, get it? Nudge-nudge, WNK-WNK (kinases), say no more? by Cao-Pham and coworkers, published in the journal, New Phytologist, in 2018. WNK kinases are a type of protein involved in signaling processes in cells. The title is a play on words on Monty Python’s “Nudge, Nudge, Wink, Wink, Say No More” sketch. Should Y stay or should Y go: The evolution of non-recombining sex chromosomes by Sun and Heitman, published in the journal, Bioessays, in 2012. The authors discuss the possibility that the Y chromosome (where the genetic information to make a male is located), will degenerate and disappear. The title is a play on words on the song Should I Stay or Should I Go by the band The Clash. Carbon Monoxide: To Boldly Go Where NO Has Gone Before by Stefan and coworkers, published in the journal, Science Signaling, in 2004. Nitric oxide (NO) is an important signaling molecule in the body that has been intensely studied. Carbon monoxide (CO) is also a signaling molecule, but it has not been studied as well as “NO”. The authors use a phrase from the epic introduction to the episodes of the Star Trek series to suggest that the research of “CO” should follow in the footsteps of the research of “NO”. Some titles of scientific articles are just too clever: Friends with Benefits: On the Positive Consequences of Pet Ownership by McConnell and coworkers, published in the journal, Journal of personality and Social Psychology, in 2011. Lasagna plots: A saucy alternative to spaghetti plots by Swihart and coworkers, published in the journal, Epidemiology, in 2010. “Spaghetti plots” are a type of graph for visualizing data. The authors suggest that what they call a “Lasagna plot” is a better alternative in some situations. You Probably Think this Paper’s About You: Narcissists’ Perceptions of their Personality and Reputation by Carlson and coworkers, published in the journal, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, in 2012. Here I should clarify that scientists use the word “paper” to refer to a scientific article. Can you tell your clunis from your cubitus? A benchmark for functional imaging by Fisher and coworkers, published in the, British Medical Journal, in 2004 This is related to the phrase “Can’t tell your arse from your elbow” (intended to mean someone is stupid or ignorant), but using the Latin names. The authors stimulated the clunis and cubitus of volunteers and then imaged their brains to see if they could discriminate the areas that were activated. Different strokes for different folks: the rich diversity of animal models of focal cerebral ischemia by Howells and coworkers, published in the journal, Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, in 2010 “Different strokes for different folks” is a phrase indicating that different things appeal to different people. “Focal cerebral ischemia” is a stroke. The authors state that any of the many different animal models that are used by scientists to study a stroke contain some (but not all) of the variables that are found in human disease strokes. Some of the scientific article titles are naughty: Sex with Knockout Models: Behavioral Studies of the Estrogen Receptor Alpha by Rissman and coworkers, published in the journal, Brain Research, in 1999. This is not about getting intimate with stunningly beautiful people who model apparel. In molecular biology, knockout models are organisms such as mice that have had a particular gene inactivated (knocked out). In this article the authors describe how knocking out the estrogen receptor alpha gene in a lineage of mice affects their sexual behavior. Neuronal Ca2+: Getting it up and Keeping it up by Richard Miller, published in the journal, Trends in Neurochemical sciences, in 1992. Ionic calcium (Ca2+) is an important molecule used by neuronal cells for signaling events. The article is about generating the calcium signal (increasing the levels of ionic calcium or “getting it up”) and maintaining it (“keeping it up”), although the title makes you wonder. Proton-Enhanced Nuclear Induction Spectroscopy. 13C Chemical Shielding Anisotropy in Some Organic Solids by Pines and coworkers, published in the journal, Chemical Physics Letters, in 1972. If you don’t get what’s naughty about this, I will give you a clue: “acronym”. Yes, they coined the name on purpose to spell that out! Pillow talk by Dewit and Stern, published in the journal, Journal of Volcanology, in 1978. Here “pillow” is a lava flow that contains pillow-shaped structures as a result of having occurred underwater. New soft robots really suck: Vacuum-powered systems empower diverse capabilities by Robertson and Park, published in the journal, Science Robotics, in 2017. Practice makes perfect: rectal foreign bodies by Mike Paynter, published in the journal, Emergency Nurse, 2008. In some articles the authors tried to be funny, but what came out was at best “dark humor” or at worse inappropriate or insensitive: From urethra with shove: Bladder foreign bodies. A case report and review by Nazir and Runyon, published in the journal, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, in 2006 Ouch! The urethra is the duct that connects the bladder to the exterior and which is used for voiding urine. The title is a play on words on the James Bond movie: From Russia with Love. “Here's egg in your eye”: a prospective study of blunt ocular trauma resulting from thrown eggs by Stewart and coworkers, published in the journal, Emergency Medicine Journal, in 2006 The title is a play of words on the expression “egg on your face”. A lucky catch: Fishhook injury of the tongue by Eley and Dhariwal, published in the journal, Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, in 2010. Children and mini-magnets: an almost fatal attraction by McCormick and coworkers, published in the journal, Emergency Medicine Journal, in 2002. Ashes to ashes: thermal contact burns in children caused by recreational fires by Cahill and coworkers, published in the journal, Burns, in 2008. And finally last, and definitely least, we have the scatological humor category. The first three entries belong to the never ending source of juvenile humor involving the study of the seventh planet of our solar system and a very well-known elementary school pun: Chemical processes in the deep interior of Uranus by Chau and coworkers, published in the journal, Nature Communications, in 2011. The Dark Side of the Rings of Uranus by Pater and coworkers, published in the journal, Science, in 2007. Plumbing the depths of Uranus and Neptune by Peter Read, published in the journal, Nature, in 2013. In this last one, some people would claim that the author tempered his peculiar choice of verb by also including the planet Neptune in the title to maintain “plausible deniability”! Then we move on to word play: Fire? They Don't Give a Dung! The Resilience of Dung Beetles to Fire in a Tropical Savanna by Nunes and coworkers, published in the journal, Ecological Entomology, in 2018. Getting to the Bottom of Anal Evolution by Hejnol and Martín-Durán, published in the journal, Zoologischer Anzeiger - A Journal of Comparative Zoology, in 2015. In the final entry below, the authors ditched all pretense of subtlety by writing it like it is, and someone let them get away with it! An In-Depth Analysis of a Piece of Shit: Distribution of Schistosoma mansoni and Hookworm Eggs in Human Stool by Krauth and coworkers, published in the journal, PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, in 2012. And that’s all for now. Do you have any favorite funny scientific titles? Leave a comment and share it here. The Smiley jackass head and neck Free SVG by OpenClipart is in the public domain. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed