|

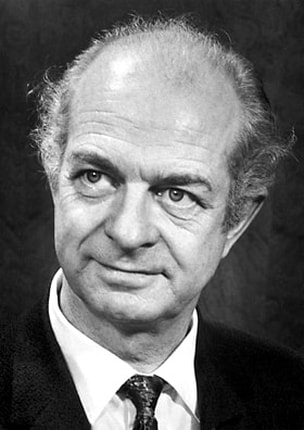

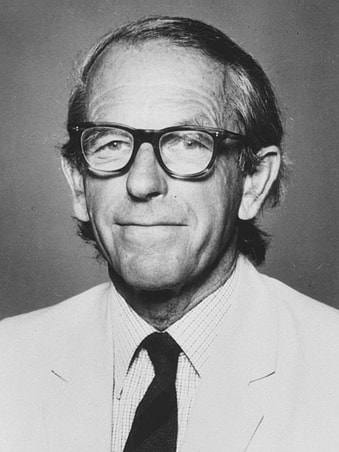

Winning the Nobel Prize is a crowning achievement for any scientist. It is recognition that said scientist has had a real world impact and made a major contribution to the advancement of knowledge. Nevertheless, there are some drawbacks to winning the Nobel Prize. Upon reading this, some scientists would reply, “Oh, yeah? Just try me!” I know. I know. Most scientists would rather have a Nobel Prize than not. But one of the problems with a Nobel Prize is the perception that it represents the peak in a scientist’s career, and that from there on it’s mostly a downhill ride. Now, don’t get me wrong. Most scientists remain active in research and make many important contributions after winning a Nobel Prize. But the majority of scientists remain active in the field in which they won the prize, as opposed to switching to a different field and making a new discovery. Therefore their work after winning the prize is often perceived to be the fill-in work by individuals engaged in an activity characterized by diminishing returns. It is difficult to shake off the notion that, if you’ve won a Nobel Prize, you are a “has been” whose future work will never reach the level achieved by your earlier work. However, what if you won a second Nobel Prize? Now, that would be something, wouldn’t it? It would very clearly convey the message that you’ve still have “IT”. So has anybody achieved this feat? In the 119 years during which the Nobel Prizes have been awarded, only four individuals have achieved this.  Marie Curie Marie Curie Marie Curie Marie Curie was a Polish-French physicist and chemist who, along with her husband, Pierre Curie, performed important work in the emerging field of radioactivity. For this work they shared the Physics Nobel Prize in 1903 with another pioneer in radiation studies, Henry Becquerel. Interestingly, and reflecting the prejudice of the times, the French Academy of Sciences was considering only nominating her husband and Becquerel for the award, but Pierre Curie complained that her contribution was also important, and they were both nominated and won. Marie Curie won a second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, in 1911 for her work in discovering the new elements Radium and Polonium (her husband had died in an accident in 1906). She is so far the only woman to have earned two Nobel prizes, and only one of two persons who has earned the prize in separate disciplines. It should be mentioned here that Marie’s daughter, Irene Joliot-Curie, along with her husband Frederick won the Nobel Prize in 1935 in chemistry for their synthesis of new radioactive elements. This makes the Curies the winningest family when it comes to Nobel Prizes, with a total of five!  Linus Pauling Linus Pauling Linus Pauling Linus Pauling was an American chemist and biochemist who performed important work in the structure of biological molecules and the nature of the chemical bond. For his work he was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1954. Pauling remained active in this area, but his concerns regarding the proliferation of atomic weapons led him to spearhead a movement to reduce the number of atomic weapons and ban their testing. For his activism, Pauling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Peace in 1963. Pauling was the second person (after Marie Curie) to win two Nobel Prizes in different disciplines, but in his case he was the sole winner. He did not share his prizes with anyone!  John Bardeen John Bardeen John Bardeen John Bardeen was an electrical engineer and physicist who with Walter Brattain invented the transistor while working at Bell Labs in 1947. This invention caused a revolution in the field of electronics and made possible most modern electrical devices that we use today. For their work, Bardeen and Brattain were honored with the Nobel Prize in physics in 1956, which they shared with William Shockley. However, after Bardeen left the emerging transistor field, he developed, along with Leon Cooper and John Schrieffer, a theory to explain the phenomenon of superconductivity (commonly called the BCS theory), for which all three were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1972. In this way, Bardeen became the first individual to receive the Nobel Prize for work carried out in two fields of research within the same discipline!  Frederick Sanger Frederick Sanger Frederick Sanger The British biochemist, Frederick Sanger, was the first person to sequence and determine the structure of the very important protein hormone, insulin. This achievement not only revolutionized the study of proteins but also paved the way for the production of synthetic insulin. For this achievement he received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1958. Sanger then, focused his energies on DNA, the molecule that carries the instructions to produce living things. He devised methods to determine the long sequences of this molecule, and this achievement led to the determination of sequences of DNA and related molecules from many organisms including humans, as well as to the identification of the DNA changes underlying genetic diseases. Sanger’s methodological contributions also served to launch the modern disciplines of molecular biology and biotechnology. For these achievements, Sanger received again the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1980, which he shared with Paul Berg, and Walter Gilbert, thus becoming the second person ever to have received two Nobel Prizes in the same discipline. No one has won two Nobel Prizes since Sanger in 1980, and no one has won them in the discipline of physiology and medicine. Similarly, no one has won three Nobel Prizes (and some people would argue that the human lifespan and the dynamics of Nobel Prize worthy achievements are such that this is impossible). So far, Marie Curie, Linus Pauling, John Bardeen, and Frederick Sanger represent or are very close to the peak performance attainable by the human mind in the field of science. After winning their first Nobel Prize, these people proved to the world that they still had “IT”! The 1911 photograph of Marie Curie published in 1912 in Sweden (Generalstabens Litografiska Anstalt Stockholm) is in the public domain. The 1962 photo of Linus Pauling and the 1955 photo of John Bardeen by the Nobel foundation are in the public domain. The NIH photo of Frederick Sanger is in the public domain.

0 Comments

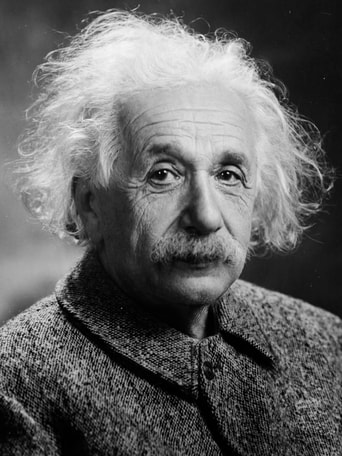

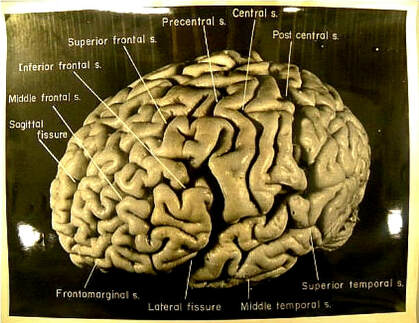

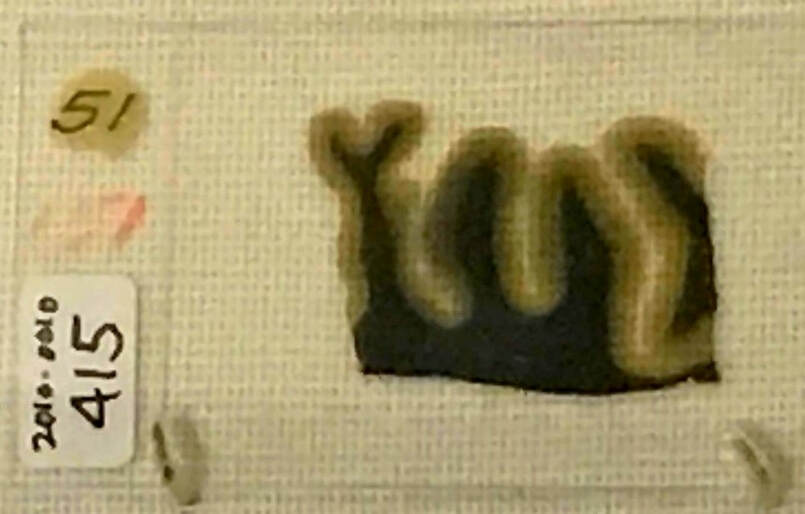

Albert Einstein Albert Einstein Albert Einstein was one of the towering figures of the twentieth century. Images of his face surrounded by a fluffy mat of white hair have become synonymous with genius in both popular and scientific cultural circles. Einstein’s contributions in many areas of physics range from the explanation of the photoelectric effect, the equivalence of energy and mass as defined in his famous E = MC2 equation, his reinterpretation of Newtonian mechanics (special theory of relativity), and his description of gravity as a property of space and time (general theory of relativity), to his work towards elucidating the nature of light, the existence of the atom, and the establishment of quantum mechanics. He predicted the existence of Bose-Einstein condensates, gravitational lensing, and gravitational waves, all of which have been confirmed. Einstein’s ideas resulted in practical applications in areas such as nuclear power, space travel, fiber optics, GPS, and computers, but his thinking has also influenced disciplines as varied as philosophy, art, and literature. It is not an overstatement to assert that this individual changed the world. As we stand in awe admiring Einstein’s accomplishments, we wonder where all that came from. Ideas, inspiration, and creativity are attributes that we associate with one organ in the body: the brain. Therefore, if Einstein was able to think all of these things up, but most other human beings are incapable of such feats, it follows that there must be something special about Einstein’s brain: something that differentiates it from the brain of common individuals, something that makes him vastly smarter. The reasoning then goes: if we find that something, that difference between Einstein’s brain and the brain of common folk, we will have found the nature of genius, the seat of intelligence.  Einstein's Brain Einstein's Brain Einstein may have been curious about the above line of reasoning, but there is one thing we know for certain: he was aware of his fame, and he did not want to be idolized after his death. He left instructions that his body be cremated and his ashes scattered. However, when Einstein died in 1955, the temptation was too much for the Princeton Hospital pathologist that performed the autopsy; Thomas Harvey. Going against the wishes of Einstein’s family, Harvey removed Einstein’s brain. When the family found out, there was some acrimony, but Harvey managed to obtain permission from Einstein’s oldest son to keep the brain as long as it was used for scientific studies. When the hospital administrator found out what he did, Harvey was fired. He went on to practice medicine but eventually was not able to renew his medical license. His marriage ended in divorce, and he ended up working on the assembly line of a plastics factory to pay his bills. Harvey took pictures and measurements of Einstein’s brain, and he had parts of the brain sectioned into many pieces that were treated with dyes and sealed in slides. Over the span of decades, he tried to get scientists interested in looking at the brain, but found few takers. He sent slides to several eminent scientists, but they found nothing out of the ordinary. Eventually, a few scientists became interested enough to perform detailed studies of the morphology of the brain using the slides and photos of the intact brain that Harvey had taken, and some differences were found when comparing Einstein’s brain to those of regular people. However, whether these differences are related to Einstein’s intellectual prowess, or whether they are part of normal brain to brain variation that can be encountered among individuals, is still an open question. There is the possibility that genius is not correlated with an obvious gross morphological characteristic of brains, but rather to the more subtle ways in which its billions of neurons are interconnected. There is also the possibility that genius resides in the temporal and spatial pattern in which the neurons interact with each other. If this is the case, it is likely that nothing can be learned about genius from fixed dead brains, as only detailed imaging of living brains will reveal their secrets. Today, the physiological roots of intelligence and genius remain as elusive as ever. And perhaps that is a good thing. Since human beings began to study the brain, we have woven fanciful explanations as to the nature of intelligence. First brain size was the metric that was thought to be related to intelligence. Thus, when evidence was produced that some races had different brain sizes than others, this became the linchpin of ideas regarding the superiority and inferiority of these races. When the idea that brain size among normal human beings was correlated to intelligence fell into disrepute, we developed the idea that we could test for intelligence and reduce it to a number. Then soon enough evidence was generated that some races, or social classes, or groups of people, did better on intelligence tests than others, again leading to notions of superiority and inferiority. The eugenics movement arose in the early twentieth century advocating the betterment of the intellectual level of society. In the United States, terms like “feeble-minded” and “moron” were developed to denote people who scored poorly on intelligence tests. The eugenics craze in the United States led to restrictions on immigration and forced sterilizations of tens of thousands of people, which invariably affected to a greater extent those who were poor, uneducated, and from minority groups. All these terrible ideas are discredited nowadays, at least academically, but watered down versions of these ideas still linger among the general public and some scholars. Asking questions about what made Einstein extremely intelligent are legitimate. But my fear is that if we do discover some characteristic in the brain responsible for genius, let’s call it “X”, we will again travel down this well-worn step by step path: 1) “X” made Einstein a genius. 2) Therefore, the more of “X” you have, the more intelligent you are. 3) We can classify otherwise normal individuals into whether they are more or less intelligent based of the amount of “X” they have. 4) Groups of people displaying lower levels of “X” are dumber. 5) Groups of people displaying lower levels of “X” are inferior. 6) Allowing these groups of people with less “X” to breed or to come to our country will compromise our society. 7) We must do something about it. A while ago I did something that Einstein would have disapproved of. I went to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. As part of what they call “Brain Awareness Week” they had an exhibition on Einstein’s Brain. The museum has a set of slides made from Einstein’s brain that Harvey’s estate donated after Harvey died, and some of them were on exhibit. So I took a picture (see below). This section of Einstein’s brain was stained for myelin, the protein that ensheaths the axons of neurons. The black area is the fiber tracks (the white matter in the brain), and the brown area is where the neuronal cell bodies reside (grey matter). There is (or was) something in sections like these that made possible the thinking of ideas that no one had ever thought before, revolutionizing our view of reality, and changing our world forever. What is or was that something? And if we ever discover it, what will we do with that knowledge? The photograph of Albert Einstein by Orren Jack Turner obtained from the Library of Congress is in the public domain. The image of Einstein’s brain was cropped and modified from the article: Falk, Dean, Frederick E. Lepore, and Adrianne Noe. "The cerebral cortex of Albert Einstein: a description and preliminary analysis of unpublished photographs." Brain 136.4 (2012): 1304-1327, and is used here under a NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) license. The image of the section of Einstein’s brain is by the author and can only be used with permission. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed