Many people who agree that evolution is a fact nevertheless are unconcerned with the creation/evolution debate. At most these people will express some qualms about the violation of the separation of church and state when creationists try to teach their religious beliefs masquerading as science in schools, but that’s about it. For them evolution is one of those “science things” that may be interesting to read about, but that is far removed from their everyday reality and does not affect them. Nothing could be further from the truth. First and foremost, evolution is the framework that allows us to understand how populations of living things propagate and change through time and space. Because of this, evolution has made possible the development of procedures and strategies in dozens of areas of human endeavor that involve dealing with biological entities ranging from DNA fingerprinting to fighting cancer. There are even scientific journals devoted to research into the application of evolutions such as one named (quite fittingly), Evolutionary Applications. However, in the interest of providing tangible examples, in today’s post we will go over some of the applications of evolutionary theory. Most people have taken an antibiotic during their life. The availability of antibiotics to control or prevent infections by bacteria is something we take for granted. However, bacteria are constantly evolving resistance to antibiotics, and new strains of multidrug-resistant bacteria are compromising our effectiveness to fight infections. This is a fact that can affect your health, as many people have died from infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. But is not only bacteria. Fungi are evolving resistance to antifungals, and viruses are evolving resistance to antivirals. Evolution explains why this is happening, and in the design and application of new antimicrobials, scientists have to take into account the principles of evolution to both reduce and keep up with the development of resistance by microorganisms. Beyond health, evolution also has benefited agriculture because many pests, including microorganisms, weeds, and insects, are evolving resistance to pesticides. To maintain the capacity of our farmers to peoduce enough crops to meet our food needs, scientists use the principles of evolution to manage the application of pesticides and develop new ones. In the medicines that you take and the food that you eat, you have benefited from evolution. Even before the theory of evolution was enunciated by Darwin, human beings knew how evolution worked! They knew that they could apply selection strategies to produce farm animals, dogs, plants, or other organisms that bore traits they desired. This directed breeding is nothing more than the application of evolutionary mechanisms (descent with modification) in a directed fashion (artificial selection), and today with the tools of modern genetics this process can be made faster and more effective. If you own or eat animals and plants that have been generated by directed breeding, you have benefited from evolution. Within the field of evolution there is an important subfield called phylogenetics which studies the evolutionary relationships among biological entities. This discipline, which establishes how these entities are related to one another, has been applied to a breathtaking variety of biological problems and used to answer important real-world questions ranging from the culpability of individuals accused of a crime to the importance of diversity for ecosystems. From designing vaccines and tracking epidemics to determining ancestry among individuals, it is very likely that in one way or another phylogenetics has affected your life. The Nobel Prize winning chemical engineer, Frances Arnold, has pioneered the application of the mechanisms of evolution to obtain enzymes with novel activities. Enzymes are proteins that make possible (catalyze) chemical reactions. The vast majority of chemical reactions that take place in living things are the result of enzymes. Enzymes are also used in industrial processes, and many industries would benefit from having enzymes with new or more stable activities. To generate these new enzymes, Dr. Arnold generated a population of enzymes with random changes that she had introduced into their structures, and then selected those enzymes that had an activity close to that which she desired. After many rounds of this evolutionary process, she was able to not only obtain enzymes with new activities, but also to obtain enzymes with types activities never seen in nature! Such is the power of evolution. This directed evolution strategy is now generating new enzymes that are being used in industrial processes to produce materials that you are may be using including detergents, oils, and fragrances. In the field of computer science, the mechanisms of evolution have been adapted into the so-called “genetic algorithms”. These are programs that use an evolutionary strategy to solve problems. The programs are fed a set of random attempts to solve a problem, most of which will not work, but some will work better than others. The program then chooses those attempts that worked the best, and these attempts are copied into a second generation of attempts to solve the problem but introducing random modifications into them (analogous to mutations). This cycle of choosing the best attempts at solving the problem and copying then into the next generation with random modifications is repeated hundreds to thousands of times until a solution to the problem emerges. Genetic algorithms have proven very successful at generating solutions to complex problems in fields ranging from aerospace, electric, and materials engineering, to military planning, law enforcement, medicine, and routing and scheduling. If you are enjoying the benefits of some advance in technology directly or indirectly, it is likely that along the way a genetic algorithm has been used to solve problems that made it possible. The above list (that is by no means exhaustive) shows that the theory of evolution is not something abstract that is only of interest to academics. The applications of evolution has improved the life of human beings (including creationists) by generating thousands of useful products, technologies, and insights for the solution of critical issues that affect our lives. Evolution image from Pixabay by Manoel M. Pereira Valido Filho Mvalido is free for commercial use.

0 Comments

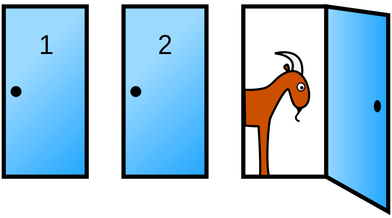

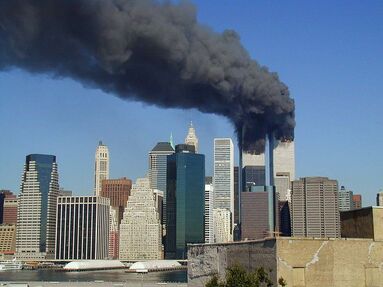

6/21/2019 The Species That Cheated Extinction: The Saga of the Lord Howe Island Stick InsectRead Now Ball's Pyramid Ball's Pyramid Ball’s Pyramid is a rock monolith that thrusts its nearly vertical basalt walls 1,800 feet over the surface of the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand. It is known as Ball’s Pyramid because it was discovered in 1788 by Royal Navy officer Henry Lidgbird Ball, who also discovered Lord Howe Island, situated 14 miles to the North. Ball’s pyramid, which is the world’s tallest sea stack (taller than the Empire State building), is the eroded remains of the caldera of an ancient volcano, and it was climbed for the first time in 1965 by a team of Australian rock climbers. But Ball’s Pyramid is famous for an incident involving an insect. Island environments throughout the world due to their isolation have a special place in evolution. It is common to find on islands living things that are not found anywhere else in the world. Such was the case of the Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis), which could grow up to 6 inches long, and was often used as bait by the local fishermen. Unfortunately, when a ship ran aground on Lord Howe Island in 1918, it introduced rats to the environment, and the rodents went on to wipe out the entire stick insect population. The last stick insect was seen in 1920, and after that year the species was thought to be extinct. Nevertheless, during the 1960’s, while climbing Ball’s Pyramid was still allowed by the Australian government, climbers sometimes reported that they saw carcasses of stick insects. However, these insects are nocturnal and nobody wanted to climb the jagged rock at night. Finally in 2001 a handful of Australian scientists risked their lives in the darkness, and a few hundred feet above the waves on the sheer rock cliff they located a population of 24 of the famed Lord Howe Island stick insects eking a living on a few plants, which in turn were precariously growing in some cracks in the rock. After more exploration, they ascertained that these were the only stick insects on Ball’s Pyramid. Imagine that, the last 24 individuals left in the whole world of a species living in an environment that could be wiped out any day by a rock slide! The insects managed to survive a few more years while the scientists battled the red tape of the Australian government before returning in 2003 to remove some pairs for breeding. The attempt was successful, and today there are thousands of descendants from those original breeding pairs. However, the newly bred Lord Howe Island stick insects looked different from specimens preserved in museums, and there was some question about whether they were a different but related species. Scientists solved this issue by applying the new tools of genomics to samples from the newly bred insects and those preserved in museums. It was determined that the newly bred insects differed genetically from museum samples by no more than 1%, which is how much samples from museum specimens differed from each other. This indicated that the newly bred insects and the original insects were indeed the same species. Thus the Lord Howe Island stick insect had evaded extinction and come back from the brink thanks to a few daring and motivated scientists, and thanks to many generations of insects that clung tenaciously to life on the windswept spire of Ball’s Pyramid. Image of Ball’s Pyramid by Fanny Schertzer is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license. Image of the Lord Howe Stick Insect by Granitethighs is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license.  Monty Hall Puzzle Monty Hall Puzzle Marylyn vos Savant is an American writer who was recognized by the folks at Guinness World Records to be the person with the highest IQ in the world before that category was eliminated from their world record groupings in 1990. Marylyn writes a weekly column for the magazine Parade, where, among other things, she solves puzzles and answers questions that her readers send to her. In 1990, one reader sent her a puzzle (named the Monty Hall Puzzle after a Canadian-American game show host) that involved a game show where you are given a choice between 3 doors. Behind one door is a car, and behind the other 2 doors there are goats. You pick one door, and the game show host proceeds to open one of the remaining 2 doors revealing a goat. The game show host then asks you if you want to switch your original selection to the other remaining door. The question is: is it to your advantage to switch your choice of doors?  World Trade Center Towers World Trade Center Towers Marylyn replied in a very matter of fact way that the answer is “Yes, you should switch”. If you keep your original choice, the odds of winning the car are 1/3, but if you switch, the odds of winning the car are 2/3. This ignited a firestorm among her readers which included quite a number of scientists. She received thousands of letters telling her that there is no advantage in switching because, as there are 2 doors left, one with a goat and the other with a car, the probability of winning the car is 1/2. Of those that wrote letters to her, only 8% of the general public and 35% of scientists thought she was right. Marylyn wrote another column maintaining she indeed was right and tried to explain her reasoning, but to no avail. The insults started coming in. Many laypeople and scientists (including mathematicians and statisticians from prestigious research centers in the country) lectured her on probability and berated her intellect, some even suggesting that maybe women think about statistics differently. In response Marylin wrote a another column asking for a nationwide experiment to be carried out in math classes and labs, in essence reproducing the problem using 3 cups and a penny. After this she was vindicated. The experiment she suggested along with simulations performed using computers, proved that she was indeed correct, and many former skeptics wrote letters of contrition apologizing for insulting her. By the time she published her last column on the subject, 56% percent of the general public and 71% of scientists (the majority) accepted that she was right. The process outlined above, displayed an initial phase of skepticism, followed by a second phase of analysis and corroboration of the claim. However, the case of the puzzle is clear cut. There is no ambiguity. Everyone could perform the experiment and convince themselves of the truth (there are even online sites that allow you to do this now). And yet, despite this, there were still a significant percentage of individuals who did not accept Marylyn’s conclusion. The two phases mentioned above are also seen in the acceptance of counterintuitive scientific theories, although the complexity of the analyses is much greater and not accessible to everyone, and the opposition from the skeptics is much stronger. This is especially true in some dramatic situations involving science where the debate spreads into the social and political realms spanning conspiracy theories. One such case is the conspiracy theory that states that the collapse of the World Trade Center Towers after the attacks of 911 was produced by demolition charges and not as a direct result of the attacks. Among the buildings that collapsed, the case of Building 7 became a lightning rod for the conspiracy theorists because of the way it was damaged and the way it fell. Building 7 was one of the buildings in the World Trade center complex. It was not targeted by the terrorists, but rather when the World Trade Center Towers collapsed, this inactivated the pipes carrying water to the sprinkler system of Building 7, and burning debris from the towers ignited fires within the offices. The fires burned for several hours, and then Building 7 collapsed in a manner that reminded both laypeople and experts of a controlled demolition. Additionally, at this time the collapse of a steel frame building such as Building 7 was unheard of. This, along with a series of interpretations of actions and communications taking place that day, led a large number of people to express skepticism that Building 7 could have collapsed due to the fire. The above state of affairs represented the initial phase of what happens when people are confronted by something that counters their sense of how things should work. Skepticism in this phase is a reasonable reaction to the information being received. Among the several investigations conducted after 911, the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST) conducted a thorough 3 year investigation that explained why building 7 collapsed in a manner reminiscent of a controlled demolition. In doing this they discovered a new type of progressive collapse which accounted for the collapse of the building which they dubbed fire-induced progressive collapse. Using simulations, they conclusively explained how a steel frame building such as Building 7 could be brought down by fires, and they ruled out other explanations. Some reasonable skeptics were still left unconvinced because, after all, no steel frame building had ever collapsed due to fire alone. However, this changed when the Plasco High-Rise building in Tehran (a steel frame building like Building 7) collapsed as a result of a fire in 2017. A very clear explanation of the above facts is presented by Edward Current in the video below.

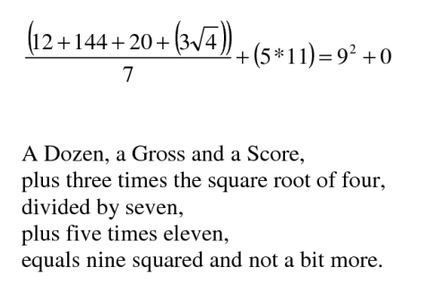

Because of this and other investigations, the scientific community today accepts the explanation that Building 7 collapsed due to fire. This was the second phase where facts were gathered, research was carried out, and the issues were explained to the satisfaction of the majority. This is not to say that there aren’t some holdouts. For example the Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth is a group that has still refuses to accept these conclusions, and in their website they boast of having 3,141 plus architects and engineers that still espouse skepticism of the accepted explanation. However, considering there were 113,554 licensed architects in the US in 2017 and 1.6 million employed engineers in the US in 2015, you can see that these individuals represent just a minority of their professions that still cling to an irrational skepticism that is unwarranted. Such is the resistance some human beings display to accepting counterintuitive facts, whether they are the solutions to a fun puzzle or the explanations behind world changing events. The Monty Hall Problem image by Cepheus is in the public domain.  The limerick is a short verse made up of 5 lines where the first second and fifth line usually share one rhyme while the third and fourth have a different rhyme. This form of verse arose in the 18th century and was popularized by the English artist Edward Lear. The limerick has become very popular in English speaking countries, and millions of them have been written. Although quite a few limericks are naughty or dirty, many limericks are used in several areas of human endeavors to convey, in a short and witty manner, important or humorous messages, or to highlight or celebrate occurrences of renown. In science, limericks have been used for many purposes and they range from those that are readily accessible to the layperson, to those that are highly technical. Today we will take a look at some science limericks. The limerick has been used by teachers as a teaching tool to help students remember their facts. An example is the following limerick by engineering Profesor Annraoi de Paor:

“Of electrical worth it’s the stamp To distinguish the volt from the amp: Should your class nod, ‘That’s true – Volts across and amps through,’ It’s sure that you’re in the right camp. This limerick is employed to tell the difference between the AMP, a unit of electrical current (through), and the VOLT, a unit of potential difference or abundance of electric charges from one point to another (across). Limericks have also been used to highlight or celebrate great discoveries. For example, this limerick is about the discovery by Paul Ehrlich of the drug Salvarsan which was controversially used to treat the venereal disease syphilis (the limerick ends with the chemical name of the drug). A chemist named Ehrlich, unclean Engaged in researches obscene He injected the poxy With bis(para-hydroxy Meta-amino arseno-benzene). The next limerick celebrates the discovery of X-Rays by Wilhelm Röntgen. The integument used so to hide The organs and bones deep inside ‘Till Röntgen discovered Rays that uncovered Whatever was wounded, save pride. The many accomplishments of Albert Einstein, especially his theory of relativity, produced several limericks including the following one: There was a young lady named Bright, Who travelled much faster than light; She set out one day, In a relative way, And came back the previous night. Although it is impossible and nonsensical, the point of the limerick is that if someone could travel at speeds faster than light, they might theoretically experience time running backwards. Some discoveries celebrated in limericks did not turn out so good, such as the limerick below by D. D. Perrin. A mosquito was heard to complain That a chemist had poisoned his brain. The cause of his sorrow Was paradichloro- Diphenyltrichloroethane! Paradichloro-Diphenyltrichloroethane is the chemical name of the insecticide known as DDT. It was effective at controlling the mosquito populations and reduced the incidence of malaria, but was found to be harmful for the environment, and its use was banned. There are some discoveries or ideas that just fire up the imagination. The following limerick is about Werner Heisenberg’s famous Uncertainty principle, which states that the speed or the position of a particle can be known, but not both: A quantum mechanic's vacation Had his colleagues in dire consternation. For while studies had shown That his speed was well known, His position was pure speculation. A favorite topic for limericks is the perplexing cat in Edwin’s Schrodinger’s famous thought experiment. For example this limerick by Karen Reid: The cat in the box still has growth Or it's dead, and infested with sloth One should not get unnerved Till the cat is observed It's a superposition of both. There is also the discovery of the structure of DNA by Watson and Crick featured in limericks such as the one below by Paul Chernoff. Two bright boffins named Watson and Crick Puzzled out what makes DNA tick. It's just like spiral stairs With the bases in pairs: How on earth did God think of that trick? And limericks inspired by Darwin’s discovery of evolution. Said an ape as he swung by his tail, To his offspring both female and male, Your descendants, my dears, In a few million years, May evolve to professors at Yale. Some illustrious scientists are known to have had a favorite limerick. The favorite limerick of the Nobel Prize winning biochemist Hans Krebs dealt with the phenomenon of fermentation. There was a young woman from Hyde, Who ate some green apples and died; The apples fermented Inside the lamented, And made cider inside her insides. The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins who coined the term “Selfish Gene” authored this limerick meant to highlight the controversial interpretation that ephemeral living things such as human beings are nothing but vessels that their immortal genes use to multiply. An itinerant selfish gene Said "bodies a-plenty I've seen You think you're so clever But I'll live for ever You're just a survival machine". The great science fiction writer and science popularizer Isaac Asimov wrote several books of what he called “Lecherous Limericks”, but he did manage to compose a few with some science like this one. Said an ovum one night to a sperm, "You're a very attractive young germ. Come join me, my sweet, Let our nuclei meet And in nine months we'll both come to term. Despite all the fun and games, limericks have also been used to criticize and humiliate people. The biochemist Stanley Prusiner proposed in 1982 a new theory to explain the cause of some diseases that were believed at the time to be produced by “slow viruses”. Prusiner claimed these diseases arose due to a pathogenic agent that, unlike viruses, contained no DNA or RNA (only protein) which he christened “Prion”. He was the object of much criticism and derision, and an anonymous limerick was circulated among several labs in the field and published in the press. There was a young turk named Stan Who embarked on a devious plan. "If I simply rename it, I'm sure I can claim it," Said Stan as he pondered his scam. "Eureka!" Cried Stan, "I have found it. Well...maybe not actually found it. But I talked to the press Of the slow virus mess, And invented a name to confound it!" However, Dr. Prusiner had the last laugh when he won the Nobel Prize in 1997! And finally, a naughty limerick regarding Edmond Halley the astronomer who discovered what is now known as Halley’s Comet. From the public, his discovery brought cheers. From his wife, it drew nothing but tears. "For you see," said Ms. Halley, "He used to come daily, Now he comes once every 70 years!" I will let you figure this one out. The image of the math limerick by Leigh Mercer, is by Dwight Sipler, and is used here under an Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed