|

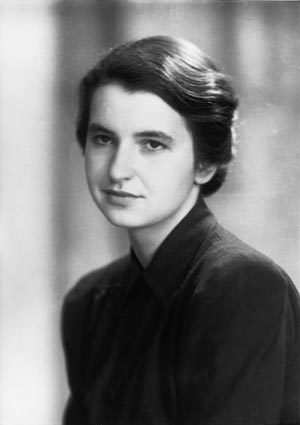

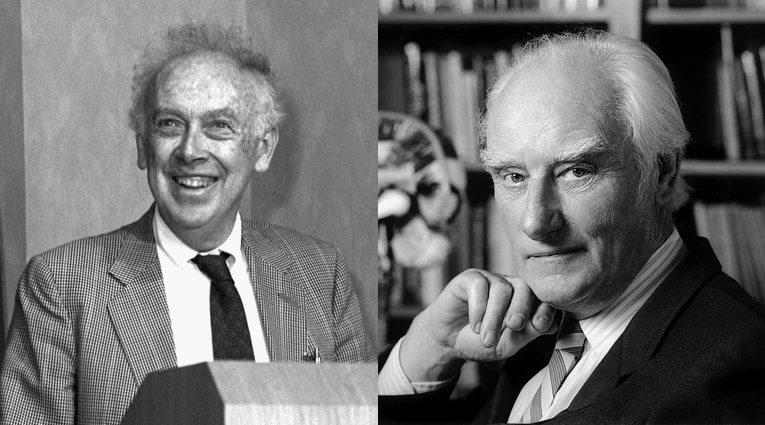

Every activity performed by groups of human beings interacting with each other tends to have some drama, and science is no exception. The quest of scientists to discover, be recognized and respected, and remain relevant has produced amazing stories that form a permanent part of the lore of scientific research. And these stories have it all: triumph and tragedy, the clash of strong willed characters, and the fireworks displays stemming from the mixing of the most honorable and dishonorable aspects of human nature. But these stories seldom make it to the end product of scientific research in which scientists report the results of their work: the scientific article. Scientific articles tend to be highly technical, full of jargon, and are mostly read by specialists. However, many scientific articles have subtle and not so subtle hints of what’s going on behind the science. Today we will take a look at two scientific articles related to two such stories. The first one is the famous article entitled, A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid, published in the Journal Nature in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick. In this article, these two scientists propose a structure for the chemical molecule that contains the blueprint of life: DNA. This article ushered a revolution that changed science and the word forever. The most mentioned passage in this article is the one below: It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material. This whopper of a sentence, which has been described as anything from “coy” to “one of the greatest understatements in the history of science”, makes a reference to the fact that the model of the structure of DNA that Watson and Crick proposed explained a phenomenon which at the time was the holy grail of the biological sciences (how genetic information is copied). However, the passage that reveals some of the human drama behind the science is found in the previous paragraph. The previously published X-ray data on deoxyribose nucleic acid are insufficient for a rigorous test of our structure. So far as we can tell, it is roughly compatible with the experimental data, but it must be regarded as unproved until it has been checked against more exact results. Some of these are given in the following communications. We were not aware of the details of the results presented there when we devised our structure, which rests mainly though not entirely on published experimental data and stereochemical arguments.  Rosalyn Franklin Rosalyn Franklin Watson and Crick never worked with DNA themselves. As they wrote, they relied on work already published by others and on their own theorizing. However, they claim their model agrees with “more exact results” in the following communications. This makes an allusion to two additional articles published simultaneously with theirs by other researchers. Among them was Rosalyn Franklin. Watson and Crick claim they were not aware of the “details” of these results when they put their model together, but this carefully worded statement is misleading. Franklin’s work with DNA was made available to Watson and Crick without her knowledge, and whether detailed or not, it was a crucial part of the puzzle that allowed them to solve the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick would go on to be corecipients of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1962. Rosalyn Franklin continued her work and went on to make several important discoveries, but died from Cancer in 1958 at the age of 38 never having known that it was her uncredited work that allowed Watson and Crick to figure out the structure of the molecule of life. The second article we will consider today is famous because of its infamy. It is entitled: Warburg Effect Revisited: Merger of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and was published in the journal Science in 1981 by Efraim Racker and Mark Spector.  Efrain Racker (left) and Mark Spector (right) Efrain Racker (left) and Mark Spector (right) In the late 1970s, Efraim Racker was one of the surviving elder scientists of biochemistry. He had won numerous awards for his work but not the Nobel Prize. When the 1978 Nobel Prize was awarded to Peter Mitchel for his theory regarding how cells obtain their energy, there was consternation in the scientific world as it had been Racker who had performed the experiments that had conclusively demonstrated Mitchel’s theory to be true. Undeterred by this, at the beginning of the 1980s, Racker took up researching an unexplained phenomenon that he had addressed off and on throughout his career called the Warburg Effect. Normal cells use oxygen as part of the normal mechanism of producing the energy they need. However, when cells become cancerous, they switch their energy producing mechanisms, in large part, to one that does not require oxygen even if oxygen is present. Many scientists think that this switch holds the key to explain what causes cancer and how it can be treated. At the same time a bright Ph.D. student named Mark Spector joined Racker’s lab and began researching the Warburg Effect. Spector proved to be a talented researcher making discoveries in a few months that would take others years. By 1981 he had put together a wonderful story linking cancer-causing genes to signaling pathways that led to changes in the bioenergetics of the cells which explained the Warburg Effect. This result was really big, and probably Nobel Prize material. The Warburg effect’s relation to cancer had not been explained for decades. Racker was elated. The passage in the article that best describes the sense of fulfilment, optimism, and aspirations that Racker had is the first sentence which is not even a scientific statement but a quote from the English writer Gilbert K. Chesterton. There are no rules of architecture for a castle in the clouds. And herein lies the brutal irony of this story. Spector tuned out to be a con-man. He had falsified the data! Racker retracted the article and dismissed Spector from his lab. Racker would still perform important research for the next decade, but the Nobel Prize would elude him. He died from a stroke in 1991. The Warburg Effect remains unexplained, and is still an active area of investigation in cancer. These are but two of the thousands of stories lurking behind the technical jargon, the graphs, and the tables in the pages of the scientific literature. Photos of Rosalind Franklin by Silver Screen and of James Watson by the National Cancer Institute are in the public domain. Photo of Francis Crick by Marc Lieberman used here under an Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5) license. I do not own the copyright to the articles mentioned here from which the text is quoted or the image of Efrain Racker and Mark Spector from the journal Science (Vol. 214, No. 4518 (Oct. 16, 1981), pp. 316-318), Copyright Cornell University. These are used here under the doctrine of Fair Use.

0 Comments

|

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed