|

One of the accusations that I often hear nowadays is that a given person arguing for something is biased. Those who promote conspiracy theories use this very epithet against anyone who dares to criticize them, and likewise, those who dismiss conspiracy theory proponents argue that they are the ones who are biased. In the popular mind, a “bias” is a negative thing to have, and the condition of being biased is synonymous with not being able to know the truth. The “bias” label is particularly contemptuous when levied against a scientist. After all, scientists are in the business of discovering the truth about the way matter and energy behave in the world around us. How can scientists discover the truth if they are biased? In popular culture a biased scientist is as blind as a bat incapable of echolocation, and whatever science they do will not reflect reality. Let’s first address this issue by stating the obvious. We are all biased, and most of the time the biases we have are not something we have consciously chosen to have, but rather they are a consequence of the way the wiring of our brain has interacted with our particular life experience and the stimuli to which we are currently exposed. But being biased is not something that is necessarily negative. In fact, as it turns out, bias has a useful function! It allows us to simplify the complexity of our world in order to gain a measure of control over it. A bias allows us to quickly take action rather than be paralyzed by a multiplicity of seemingly equivalent alternatives. From this point of view, bias actually has a survival value and may have played a role in the successful evolution of our species. The downside of bias is, of course, that you will blind yourself to the truth. Thus, to avoid bias, some people suggest that we should keep an open mind. However, this suggestion, although well meaning, is misguided. If you keep your mind too open, people will dump a lot of trash into it. The proper way to deal with bias is not to keep an open mind. The proper way to address bias is to strike a balance; what I call “finding the Goldilocks zone”. This entails accepting that we are all biased, that we can’t help being biased, and that, in fact, a bit of bias can be a good thing, while at the same time taking steps to counter the excess bias in ourselves through thought and action. Now let me tell you how scientists do this. But before I do that, let’s state that science has a healthy inbuilt bias. Science has a bias for established science. The majority of scientists believe that accepting something as true when it is false, is a greater evil than rejecting something as false when it is true. This is because established science has at least grasped some aspects of reality. If other scientists want to replace established science with a more complete description of reality, then the burden of proof is on them. This bias for established science is needed to protect science from error. Thus, you may ask: If scientists are biased for established science, how can they discover anything new? The answer is by using anti-bias protocols. For example, scientists will analyze or score the results of some experiments in a blind fashion. This involves the person doing the scoring or the analyses not knowing the identity of the different experimental groups. In clinical trials this involves the patients not knowing which treatments they received or even both the patients and the doctors not knowing which treatment is which (double blind protocol). Scientists will also seek to reproduce each other’s observations or experimental results. If an observation or an experimental result cannot be reproduced, then it will not gain traction. Finally, some funding agencies will devote a certain amount of their resources to funding scientists with unorthodox views to promote the debate of alternative views in a scientific field. But how can non-scientists counter their biases? First of all, you have to be exposed to all the facts. For example, if you listen only to conservative or liberal media, you will not learn about some issues or views. You need to listen to the other side. However, this does not mean that you have to force yourself to listen the conspiracy-laden drivel coming out of far right or far left media. Instead try to locate a moderate news source or a news source that leans slightly towards the opposite side of the political spectrum that you favor. The idea is not to open your mind to what these news outlets have to say, but rather to become aware of the issues they are covering, why they find them important, and what their arguments are. Avoid insulating yourself and living in an “echo chamber”. Second, try to identify a person from the other side who holds views different from yours and sit down to have a talk one day. But when I say “person”, I don’t mean a nutjob who spews far-out nonsense and will engage you in a shouting match. Choose a reasonable person. There are quite a number of these out there. A rule of thumb to choose a reasonable person is to look for someone who, despite disagreements, accepts that “the other side” has made valuable contributions and is necessary to the debate. Nothing beats discussing issues with an individual who disagrees with you but also respects you. And finally, learn to identify the characteristics of bias. Sweeping generalizations, innuendo, exaggerations, hearsay, judging the many by the actions of the few, the creation of strawmen, ignoring weaknesses in arguments, not seeing the forest for the trees, and attacking the person instead of the argument are all things that signal an emotional and irrational approach to issues that is indicative of a person who is biased and therefore unable to correctly grasp reality. Ask yourself if you are exhibiting these traits when you engage in arguments. Ask others who will tell you the truth if you are exhibiting these traits. So to wrap it up, a little bias is acceptable and even healthy, but too much bias can mess up your perception of reality. When it comes to bias, try to find the Goldilocks zone. The image “Goldilocks tastes the porridge” from the New York Public Library is used here under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication ("CCO 1.0 Dedication") license.

0 Comments

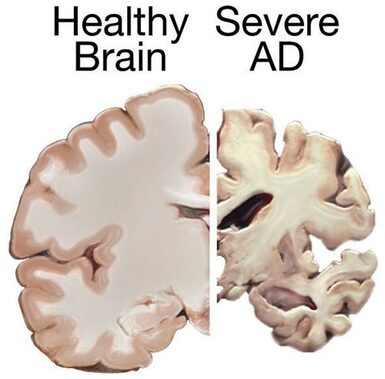

In this blog I have pointed out that there is a progression in emerging fields of scientific inquiry where competing theories are evaluated, those that do not fit the evidence fall out of favor, and scientists coalesce around a unifying theory that better explains the phenomena they are studying. However, even as a new theory that better fits the available data is accepted in the field, there are individuals who contest the newfound wisdom. Instead of accepting the prevailing thinking, these individuals buck the trend, think outside the box, and propose new ways of interpreting the data. I have referred generically to individuals belonging to this group of scientists that “swim against the current” as “The Unreasonable Men”, after George Bernard Shaw’s famous quote, and I have stated that science must be defended from them. The reason is that science is a very conservative enterprise that gives preeminence to what is established. Science can’t move forward efficiently if time and resources are constantly diluted pursuing a multiplicity of seemingly farfetched ideas. However, this is not to say that the unreasonable man should not be heard. There are exceptional individuals out there who have revolutionary ideas that can greatly benefit science, but there is a time for them to be heard. One such time is when the current theory fails to live up to expectations. I am writing this post because such a time may have come to the field of science that studies Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating dementia that currently afflicts 6 million Americans. The disease mostly afflicts older people, but as life expectancy keeps increasing, the number of people afflicted with AD is projected to rise to 14 million by 2050. The disease is characterized by the accumulation of certain structures in the brain. Chief among these structures are the amyloid plaques, which are made up of a protein called “beta-amyloid”. The current theory of AD pathology holds that it is primarily the accumulation of these plaques, or more specifically their precursors, which is responsible for the pathology. Therefore, it follows that a decrease in the number of plaques should be able to alleviate or slow down the disease. This has been the paradigm that pharmaceutical companies have pursued for the past few decades in their quest to treat AD. Unfortunately, this approach hasn’t worked. For the past 15 years or so, every single therapy aimed at reducing the amount of beta-amyloid in the brain has led to largely negative results. In fact, some patients whose brains had been cleared of the amyloid deposits nevertheless went on to die from the disease. Several arguments have been put forward to explain these failures. One of them is the heterogeneity in the patient population. Individuals that have AD often have other ailments that may mask positive effects of a drug. According to this argument, performing a trial with patients that have been carefully selected stands a greater chance of yielding positive results. Another argument is the notion that many past drug failures have occurred because the patient population on which they were tested was made up of individuals with advanced disease. According to this argument, drugs will work better with early-stage AD patients that have not yet accumulated a lot of damage to their brains. Even though many researchers still have hopes that modifications to clinical trials like those suggested above will have the desired effect as predicted by the amyloid theory, an increasing number of investigators are considering the possibility that this theory is more incomplete that they had anticipated and are willing to listen to new ideas and open their minds to the unreasonable man.  One example of these men is Robert Moir. For several years he has been promoting a very interesting but unorthodox theory of AD and getting a lot of flak for it. He dubs his hypothesis “The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease”. According to Dr. Moir, the infection of the brain by a pathogen or other pathological events triggers a dysregulated, prolonged, and sustained inflammatory response that is the main damage-causing mechanism in AD. In this hypothesis, the production and accumulation of the amyloid protein by the brain is actually a defense mechanism! Dr. Moir agrees that sustained activation of the defense response will lead to excessive accumulation of the amyloid protein and that this eventually will also have detrimental effects. However, even though reduction in amyloid protein levels may be beneficial, accumulation of the amyloid protein is but one of several pathological mechanisms. Moir stresses that the main pathological mechanism that has to be addressed by AD therapies is a sustained immune response, which over time causes brain inflammation and damage. He considers that accumulation of the amyloid protein is a downstream event, and it is known that the brain of people with AD exhibits signs of damage years before any amyloid accumulation can be detected. But much in the same way that Dr. Moir has been promoting his unconventional theory, there are many other theories proposed by others. Oxidative stress, bioenergetic defects, cerebrovascular dysfunction, insulin resistance, non-pathogen mediated inflammation, toxic substances, and even poor nutrition have been proposed as causative factors of AD. This is the big challenge that scientists face when opening their minds to the arguments of the unreasonable man: there is normally not one but many of them! So who is right? Which is the correct theory? And why should just one theory be right? Maybe there is a combination of factors that in different dosages produce not one disease but a mosaic of different flavors of the disease. And maybe the amyloid theory is not totally wrong, but just merely incomplete, and it needs to be expanded and refocused. Or maybe the beta-amyloid theory is indeed right and all that is required for success is to tweak the trial design and the patient population. Maybe, maybe, maybe… When a scientific field is beginning, or when it looks like a major theory in a given field is in need of reevaluation, there always is confusion and uncertainty. Scientists in the end will pick the explanation(s) that better fits the data and take it from there. They did that when most scientists accepted the amyloid theory and they will do it again if this theory is found wanting. The new theory that replaces the amyloid theory will not only have to explain what said theory explained, but it will also have to explain why the old theory failed and what new approach must be followed to successfully treat the disease. In the meantime, Dr. Moir’s theory, along with a few others, is the center of focus of new research evaluating alternative theories to explain what causes AD. The amyloid theory or aspects of it may still be salvageable, but in the field of AD it certainly looks like the time for the unreasonable man has come. Note: after I posted this, I became aware of an article published in the journal Science Advances that proposes a link between Alzheimer's Disease and gingivitis (an inflammation of the gums). The unreasonable men are restless out there! The image is a screen capture from a presentation by Robert Moir on the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund YouTube channel, and is used here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use.The brain image from the NIH MedlinePlus publication is in the public domain.  When people say or write things like “nothing is impossible”, they normally mean this as a motivational slogan intended to overcome life’s difficulties. They don’t literally believe that nothing is impossible, but rather that talent, focus, hard work, and dedication can overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieve success. And you know what? I’m fine with that. It may not be accurate, but I understand that people may need a little oomph in their lives. If some accuracy needs to be sacrificed to help people succeed, I am willing to look the other way, so to speak. However, some people actually believe that the maxim “nothing is impossible” is true, and not only in the realm of personal achievements, but also in the field of science. I have had a few discussions with these mystics that left me wishing that I had applied Alder’s Razor. I have tried to explain that our world functions based on a set of rules that clearly delineate what is and what isn’t possible, and that science is in the business of finding what these rules are. In response to this, I normally get a list of things that scientist thought to be impossible that were later demonstrated to be possible, along with comments like “scientific theories have been proven false again and again” and some interspersed subtle and not so subtle hints that my mind is not sufficiently open. To these criticisms, I answer that science sometimes moves forward by trial and error, and, like these critics point out, scientists have made mistakes or have underestimated the complexity of the phenomena they were studying. But, as more knowledge was generated and explanations were refined, sufficiently developed scientific theories were established that allowed accurate discrimination of the possible from the impossible. Additionally, I have already pointed out not only that the vast majority of scientific theories have not been proven false, but that there are dangers in keeping your mind too open.

Nevertheless, the more important point, that seems to be ignored by the “nothing is impossible” crowd, is that our very lives depend on knowing what is possible and impossible in the world around us. Think about it. When we walk on a cement surface, we know that it will not suddenly turn into quicksand and swallow us up. When we approach a tree, we know it will not suddenly uproot itself and attack us. When a cloud passes over us, we know it will not suddenly turn to lead, fall, and crush us. We have a very clear understanding of how cement surfaces, trees, clouds, and myriads of other things work, and we know with absolute certainty what they can and cannot do. We know what can and cannot happen. We know what is possible and what is impossible. If this understanding of how our world works were false, our lives would be in peril. But our capacity to gain this understanding is nothing new or even limited to the human species. In nature we observe that animals also gain an understanding of how their surroundings work through individual experience and from observing other animals. They develop an understanding of what is edible and what isn’t, of what prey is safe to attack and what prey is dangerous, of what places are safe to be in and which are not, and so on. There is a rhyme and reason to this understanding that animals gain. They grasp that certain things are possible and other not, and they exploit this knowledge to negotiate the complexity of their environments and survive. The animal ancestors of humans acquired this information like other animals through their individual experience and from observing others. However, as ancient humans developed the capacity to think and communicate to an extent that was orders of magnitude higher than that of their animal kin, the knowledge they derived from experience became insufficient. There were many scary things happening in the world that they did not understand and could not control like earthquakes, storms, volcanoes, droughts, pests, and disease that could dramatically affect their lives. And there were also other things like eclipses, comets, shooting stars, or the moon acquiring a red hue that were mysterious. Ancient humans were able to formulate questions. Why did these things happen? Was there something or someone making them happen? How can I prevent bad things from happening? How can I be spared? Ignorance and fear begat superstition and the belief in the supernatural in order to allow humans to make sense of their surroundings and gain a measure of control over their existence. But then some humans started investigating how the world around them worked. They observed. They experimented. They found regularities and patterns. They asked and answered questions and made predictions based on the answers, which they then refined from experience. Science was born. And science was able to deliver explanations regarding the nature and inner workings of those scary things and those mysterious things allowing us to understand them, and in many cases control them, or at least reduce their detrimental effects on our lives. Viewed from this vantage point, science is just merely a more effective way of obtaining the information that we once obtained through experience. Knowledge of what is possible and not possible is key to our survival, and science has been the most successful way in which we gave gained this information. To those who say “nothing is impossible” I just have one word: balderdash! Image from Pixabay is free for commercial use (Creative Commons CC0)  In the popular print and social media I often spot articles about the benefits of keeping an open mind. I also read how it is very important for scientists to keep an open mind. What these articles never discuss is the danger of keeping an open mind. This danger is that you will lose your power to discriminate between sound and fallacious ideas. For example, in 1917 two girls in the village of Cottingley in England took pictures of what appeared to be fairies flying and dancing around them. Among the many people fooled into believing the pictures were real was no other than the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle. More recent examples are the comedian and trickster extraordinaire, Andy Kaufman, who in 1984 visited a psychic surgeon to treat his cancer (he died), or the actor Dan Aykroyd, of Ghostbusters fame, who believes among other things in mediums and psychics and paranormal phenomena. This is not to say that only non-scientists fall victim to keeping their mind too open. There are many scientists of renown who have ended up accepting ideas or theories that were dubious at best, or patently false at worst. The co-discoverer (along with Darwin) of the theory of evolution, Alfred Russel Wallace, was a believer in psychic phenomena and spiritualism; and led an anti-vaccination campaign. Isaac Newton, the genius behind the laws of gravitation, believed the Bible had a code that predicted the future which he tried to decipher for many years. The Nobel Prize winning physicist William Shockley invented the transistor and revolutionized society, but he also defended theories that proposed the intellectual inferiority of some races. Linus Pauling, a Nobel Prize winning chemist, advocated the use of vitamin C to cure cancer despite the evidence against it. Lynn Margulis, winner of the National Medal of Science, revolutionized the theory of evolution with the concept of endosymbiosis which postulates that mitochondria and chloroplasts originated from bacteria. She also championed several fringe theories, and joined the 911 conspiracy movement that claims that it was a false flag operation to justify the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The irony is that Margulis had been married to that great skeptic, the late astronomer Carl Sagan. Kari Mullis won the Nobel Prize for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a technique which ushered a revolution in areas ranging from medicine to forensics. Not only is he an AIDs denialist along with Peter Duesberg (see below), but he denies climate change and accepts astrology. It is important to understand that the dangers of keeping an open mind have consequences that go beyond mere public ridicule. When people in positions of eminence are swayed by erroneous ideas, this can have a negative effect on society. Consider the brilliant scientist Peter Duesberg. He performed pioneering work in how viruses can cause cancer, but he was convinced that the HIV virus did not cause AIDS. His advocacy for this idea influenced the South African president Thabo Mbeki who delayed the introduction of anti-AIDS drugs into South Africa leading to hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths. In scientific research keeping an open mind is a quandary that involves navigating between making two types of errors. The first is that a mind that is too closed will reject things as false when they are really true. The second is that a mind that is too open will accept things as true when they are really false. The intuitive way to deal with this quandary is to try to strike a balance between the extremes. However, this is not how most scientists approach the issue. Science tends to be conservative in that it gives more importance to what has already been proven. Scientists view with skepticism those trying to subvert established science. The bar is set very high for the acceptance of new ideas. Most scientists view rejecting something as false when it’s really true as a lesser evil compared to accepting something as true when it’s really false. In the end, however, it will be the evidence and its reproducibility which will make the difference.  On the other hand, in the pseudosciences and the paranormal, the advice of keeping an open mind is often dispensed by those advocating for the existence of psychic phenomena, extrasensory perception, demonic possession, ghosts, telepathy, alien abductions, clairvoyance, mediums, astrology, witches, reincarnation, telekinesis, telepathy, faith healing, and many other fantastical claims. I want to suggest that, as a first step, the safest frame of mind when considering these claims is to vanish the open mind, and assume that the persons making the extraordinary claims are at best deluding themselves, and at worst liars and cheats. This suggestion may scandalize many people, and may come across as an incredibly narrow-minded and unfair approach to investigating anything. How can you find if something is true if you are prejudiced against the possibility that it’s true? The answer is that in this fringe you are dealing with events that, in principle, run counter to well-established scientific laws, or against mountains of evidence. In other words, you are dealing with the impossible. By definition the impossible is not possible and should be treated as such. When considering these claims, if you keep an open mind, you have often lost the battle. This painful lesson has been learned by many scientists that investigated fantastical claims with an open mind just to be fooled by tricks so basic that they would make seasoned magicians roll their eyes (incidentally, this is also why it is always advisable to have a magician as a consultant when investigating these claims). Scientists are the worst possible individuals to rely upon when attempting the investigation of fantastical claims. Scientists are trained to deal with nature, and nature operates based on a fixed set of rules. Natural phenomena don’t change to prevent you from studying them. Nature doesn’t cheat, lie, or delude itself. An open mind is justified only when studying natural phenomena. An open mind in any other setting is a liability. Once you have ruled out trickery and self-delusion and stablished that what you are studying is indeed a natural phenomenon, then you can consider opening your mind to the possibility that it is true. Individuals ranging from common folk to Nobel Prize winners should always remember that if you keep your mind too open, people will dump a lot of trash in it. The image is a scan of the original Cottingley Fairy pictures and is in the public domain in the United States. The open mind image by ElisaRiva is used here under a CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed