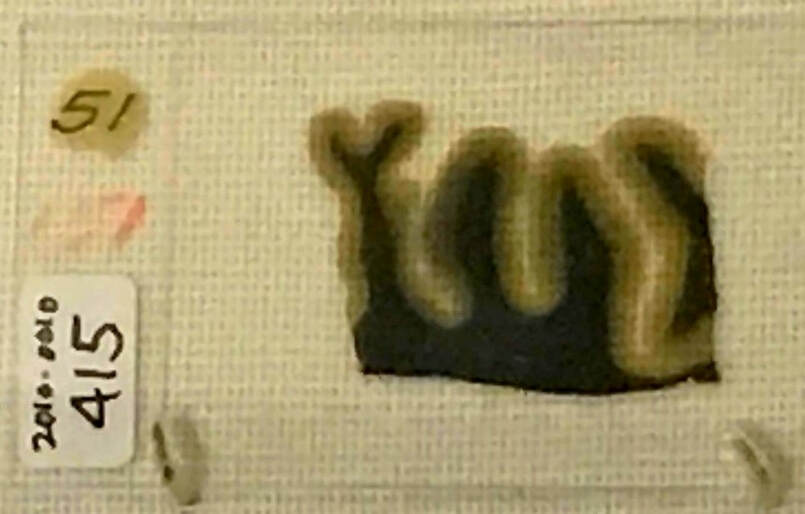

George Washington's Dentures George Washington's Dentures I recently visited the National Museum of Dentistry in Baltimore. One of their valued exhibits is the dentures of the first president of the United States, George Washington. These dentures were made out of ivory (not wood as in the popular myth) and were quite cumbersome to wear. These dentures also reflected a sad reality. In Washington’s time, most people who lived to old age had lost a significant number of their teeth. This tooth loss process, all the accompanying misery and pain associated with it, and the risks of infection and death associated with tooth extraction in those days before antibiotics an anesthesia, was made much worse by the introduction of refined sugar into Europe and North America. But I’m getting ahead of myself. What did the best minds of antiquity consider to be responsible for tooth decay? The two objects below are also at the National Museum of Dentistry. The objects are a replica of a French sculpture from the 1700s. They depict two halves of a tooth. The left half fits into the right half to reproduce the full tooth. Inside the right half there is a ghastly rendition of the fires of hell with human beings being cast into the flames. This makes a reference to the sufferings experienced by people with toothaches. The left half depicts a scene where a man is devoured by a tooth worm.  The Tooth Worm The Tooth Worm Now, what exactly is a "tooth worm"? The tooth worm was an explanation for why people experienced toothaches! It was believed that this worm appeared inside the tooth or made its way into the tooth and then caused the pain. References to the tooth worm go back thousands of years, and treatments for dental pain included strategies ranging from the chemical to the magical to coax the tooth worm out or make it go dormant. Many claimed to have found tooth worms during the process of tooth extraction, but such occurrences either had to do with regular worms that lived as parasites in the gums of individuals, or with normal structures such as tooth nerves that were mistaken for worms. The tooth worm explanation, although widespread, never led to any effective treatments or strategies for preventing toothaches or tooth decay. As science came of age, the thinking and procedures of the scientific method began to be applied to figuring out what was going on with people’s teeth. Below I present an abbreviated timeline taken from a great article by Ruby and coworkers published in the International Journal of Dentistry in 2010.

In the year 1700 the Dutch scientist, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (who invented the microscope), was sent some alleged tooth worms for analysis. He found that these worms were no different from those found in cheese, and he also isolated these worms from the mouth of people who ate said cheese. Leeuwenhoek also took samples from decayed teeth and observed they had tiny living things that he called “animalcules” (little animals), and which we now know to be bacteria. Pierre Fauchard (considered the father of mother dentistry), carried out extensive studies of diseased teeth in 1728, finding no worms, and suggested that sugar consumption enhanced tooth decay. It became clear to many scientists that there was no such thing as a tooth worm. But then, what caused tooth decay? A series of hypotheses (some nearly as fanciful as the tooth worm) were proposed from “temperature changes”, “imbalances”, and “internal factors”, to “heredity”. Several scientists in the first half of the 19th century observed that tooth decay started from the outside and proposed that it was caused by external chemical agents. Later in 1876, Pasteur demonstrated that fermentation of sugars was a chemical process caused by microorganisms. With the realization that many bacteria ferment sugars to acids, scientist like Greene Vardiman Black and Willoughby D. Miller in the late 19th century assembled the final theory that posited that bacteria ferment sugars and produce acid which erodes the dental surface producing cavities. Further work confirmed this theory and expanded it to refer to specific dental sites (plaque) and adapted it to the concept that tooth decay is an infectious and transmissible disease involving specific strains of bacteria. The understanding of the true nature of tooth decay, along with other advances, allowed the development of both preventive and restorative practices that revolutionized dental care worldwide. Today in countries like the United States, any person who follows the recommended guidelines of oral hygiene and has regular checkups performed by a dentist will experience but a tiny fraction of the dental problems suffered by our ancestors a few hundred years ago. This is the way science works. Magical thinking, superstitions, or erroneous ideas like the concept of a tooth worm that do not contribute to solving our problems fall by the wayside, and are replaced by ever more refined and focused views based on grasping aspects of reality though observation and experiment. The photographs are by the author and may be used with permission.

2 Comments

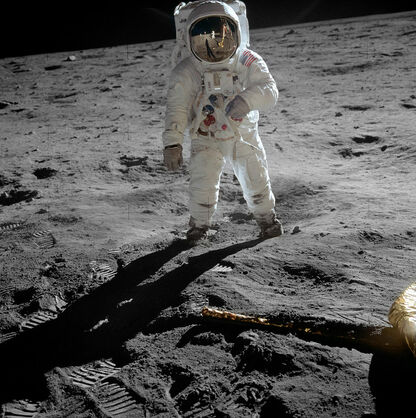

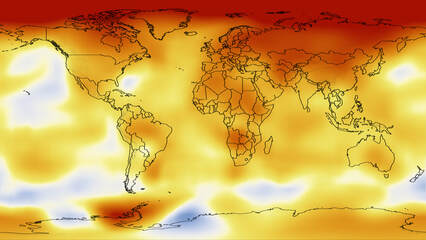

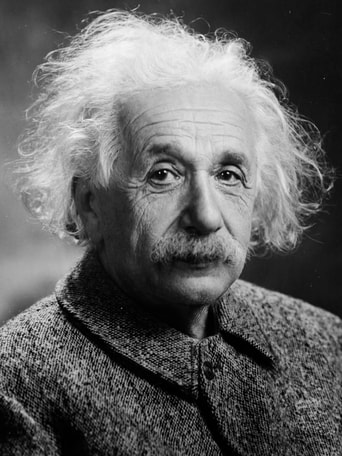

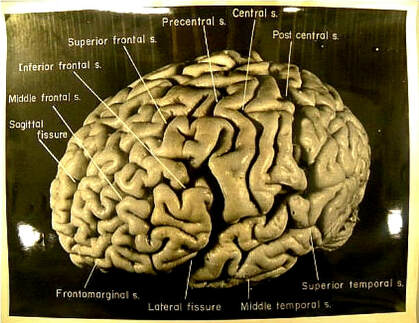

3/24/2019 Conspiracy Theorists: How to Tell the Difference between reasonable and Irrational SkepticsRead Now Terrorist attack the World Trade Center Towers Terrorist attack the World Trade Center Towers There are a lot of conspiracies out there nowadays, and many of them include scientists as the “evil guys”. Some conspiracy theorists argue that climate change isn’t real, and it’s all doctored or exaggerated data generated by scientists promoted by research funding agencies and green companies. Others argue that vaccination produces autism, and that scientists and pharmaceutical companies are trying to hide this fact. Still others argue that scientists are hiding evidence for a young Earth and the discovery of Noah’s Ark because this would confirm creationism. There are also those conspiracy theorists that state that the scientists that carried out the analyses of the destruction of the Word Trade Center by terrorist during 911 engaged in faking data and misdirection to hide the fact that the attacks were a false flag operation staged by the US government to justify the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. And there are even some who argue that the Earth is really flat, that the moon landing never happened, and that pictures of a round Earth are fake. It is tempting to roll our eyes and dismiss these conspiracy theorists as ignorant, but when you check the social media accounts of these characters and read the debates in which they become involved in public forums, you find that many of them are quite knowledgeable individuals. In fact some believers in conspiracy theories are, or have been, eminent scientists!  Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the Moon Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the Moon Conspiracy theorists and scientists share the fact that they are both skeptics, and skepticism is a healthy attitude in science. There is nothing wrong in being a skeptic, and truth be told, conspiracies should not be dismissed outright either as there have been a number of documented conspiracies. But many would argue that when it comes to some of the conspiracy theories outlined at the beginning of this post, conspiracy theorists are going too far in their skepticism and are not behaving like true scientists. So how do we differentiate between the reasonable skeptics and the irrational skeptics? How do we determine when conspiracy theorists are not behaving like true scientists? I have stated before that, unlike other disciplines, the reason that science can be right is that it can be wrong. In other words, scientific claims can be tested and proven wrong, if indeed they are. On the contrary, non-scientific claims can never be proven wrong. The proponents of non-scientific claims constantly move the goalposts and engage in fancy rationalizations to explain away the data that disprove their ideas. This is one of the characteristics of many conspiracy theorists. It is impossible to prove they are wrong, and in fact many of them when backed into a corner will argue that the mere act of trying to discredit their ideas is further proof that there is a conspiracy! It is important to identify these individuals in order to avoid getting sucked into pointless debates that will consume a lot of your valuable time. So here is the question you should ask conspiracy theorists: What evidence will convince you that you are wrong, and, if such evidence is produced, will you commit to changing your mind? If a conspiracy theorist cannot answer this question with examples of such evidence, and make the commitment to change their minds if said evidence is produced, then you can infer they are not behaving scientifically. This is one of the differences between a reasonable skeptic and an irrational skeptic.  Warming World Warming World There is another big difference between reasonable skeptics and irrational skeptics. Most conspiracy theorists are individuals who are perfectly comfortable with sitting smugly in their corner of the internet engaged in ranting out against their favorite targets to their captive audiences, but do nothing to settle the issue. Reasonable skeptics, on the other hand, do something about it. I have already mentioned in my blog the case of Dr. Richard Muller, a global warning skeptic who decided to check the data for himself. He got funding, assembled a star team of scientists (one of them would go on to win a Nobel Prize), and reexamined the global warming data in their own terms with their own methods. He concluded that indeed the planet was warming and that human activity was very likely to be the cause. This is the way rational skeptics behave. Why don’t proponents of the flat Earth theory band together, raise money, and send a weather balloon with a camera up into the atmosphere, or finance an expedition to cross the poles? Why doesn’t the anti-vaccine crowd fund a competent study to assess the safety of vaccines? Why don’t those that argue that scientists are hiding evidence of a young Earth finance an investigation employing valid methods to figure out the age of rocks? Why don’t 911 conspiracy theorists finance a believable attempt to try to model the pattern of collapse of the Word Trade Center buildings according to evidence? The answer is very simple, and it is the reason why fellow global warming skeptics repudiated the results of Dr. Richard Muller when he confirmed global warming is real. It’s because for the irrational skeptic, truth is a secondary consideration. Irrational skeptics are so vested in their beliefs and/or ideas that their main priority is to uphold their point of view by whatever means necessary. No fact or argument will sway them, no research or investigation is necessary. Because of this, when it comes to these characters, the best course of action is to apply Aldler’s Razor (also called Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword) which states that what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating. The World Trade Center photograph by Michael Foran is used here under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. Photo of Buzz Aldrin by Neil by Armstrong, both from the NASA Apollo 11 mission to the moon, is in the public domain. The image of a 5-year average (2005-2009) global temperature change relative to the 1951-1980 mean temperature was produced by scientists at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and is in the public domain. I am not really the explorer type. Some folks go backpacking into the wilderness for days on end. They sleep on the forest floor, cook their meals (if at all) over a fire, take care of their excretory business in the bushes, and brave ticks and other critters. Not me. I like a comfortable bed to sleep on, nice hot meals cooked on a stove or in a microwave oven, and adequate bathroom facilities. This is not to say that I don’t enjoy hiking in state or national parks, but for me these are affairs that only last a few hours, and the trails that I follow are always relatively close to civilization, which is a good thing as I sometimes get lost even on marked trails! Perhaps some people would argue that I am missing something, the type of communion with nature that can only come from getting away from it all, but I disagree. While my residence is located in good old suburbia, I also happen to live near a small lake that has a pleasant paved hiking trail around it. My neighborhood is also crisscrossed by swaths of woodland and little streams. As a result of this we have quite a rich fauna in our locality, which I have enjoyed looking at and photographing over the years. Sometimes I see an interesting bird or animal out near the lake, and sometimes I don’t even have to leave the house as they come to my bird feeders. So in this post I have decided to present the pictures I have taken over the years of some of the fauna of my neighborhood, all with their respective scientific names of course. The most ubiquitous patrons of my bird feeders are the sparrows (Passer domesticus). These noisy, opportunistic, little guys perch on the seed feeder and the suet feeder, and also roam the ground under the feeders looking for spilled seeds. I also have male and female cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) that always show up at the same time, so they may be a couple. Every now and then I get a house finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) which competes with the sparrows for perching on the seed feeder. On the other hand the white-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) doesn’t have the stomach for conflict. This nervous little bird waits until everyone else is gone, and then shows up, takes a bite out of the suet feeder or a seed out of the seed feeder, flies away, and repeats the process until it has had its fill. My suet feeder is also frequented by a downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) and by the larger red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus). As with the house finch, the sparrows often engage in inter-species conflict with the smaller woodpeckers for access to the suet feeder. In contrast the mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) stays on the ground prospecting for seeds and minds its own business. However, when the starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) turn up, everyone else flees the place. The Starlings are the hooligans of the crowd at my bird feeders. They monopolize the seed feeder, even though they can barely perch on it, and they pile onto the suet feeder and fight each other. Transitioning now to the birds of our lake, I often spot a single great blue heron (Ardea Herodias) which is often seen standing motionless near the shore. If you observe it long enough you will see it thrusting its beak with lighting speed into the water to catch fish. During the Fall and Winter months we have an itinerant population of ruddy ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis). During the winter a flock of herring gulls (Larus argentatus) also make themselves at home in our lake, whereas the robin (Turdus migratorius) is seen from spring to fall. Also from spring to fall you spot a crowd of small skittish birds that are hard to photograph (I don’t have a telephoto lens) like the red duck (Aythya americana) and the hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), which make our lake a home. I have sometimes seen red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), which are a bit of a rarity, but even rarer is to see a mute swan (Cygnus olor). In contrast Canada geese (Branta Canadensis) are a more permanent fixture of our lake, but the only birds that you find every day all year around are the mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). Among the remaining birds I’ve seen but have not managed to produce halfway decent photographs of, are coots, grebes, egrets, chickadees, canvasback and ring-necked ducks, scaups, green herons, gold finches, dark-eyed juncos, tufted titmice, blue jays, wrens, hawks, and strangely enough, crows. For several years there was a fallen tree sticking out into the lake that was favored by many of the mallard ducks as a place to rest and soak the sun (note the white albino duck among the flock). When the mallards were not present the turtles emerged from the lake and took over this prized spot. These snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentine) are the only reptiles I will be showing here. I have seen a snake or two, but I could never photograph them before they fled into the bushes. Moving on to mammals, I took a picture of this groundhog (Marmota monax) which had been chased by a dog up a tree. It is rare to be able to get close to a beaver (Castor Canadensis) or photograph one during the day as they are crepuscular (dawn or dusk) creatures, but the animal in the picture below didn’t seem to be doing very well, and sadly it disappeared during the winter of that year. Our lake went a few years without beavers, but they have made a comeback, as we now have an active beaver lodge. My final two pictures are one of a white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and one of a cat (Felis catus). Deer in the East Coast of the US are more abundant now due to lack of predators than they were 100 years ago, and while we don’t think of cats as wild animals, there are millions of domestic and feral cats living now in the US which altogether kill a significant number of birds and small mammals every year. I have also seen a couple of foxes, but alas, I didn’t have my camera with me. So, this is the fauna around my neighborhood. What have you seen around yours? The photographs are by the author and can be used with permission.  Albert Einstein Albert Einstein Albert Einstein was one of the towering figures of the twentieth century. Images of his face surrounded by a fluffy mat of white hair have become synonymous with genius in both popular and scientific cultural circles. Einstein’s contributions in many areas of physics range from the explanation of the photoelectric effect, the equivalence of energy and mass as defined in his famous E = MC2 equation, his reinterpretation of Newtonian mechanics (special theory of relativity), and his description of gravity as a property of space and time (general theory of relativity), to his work towards elucidating the nature of light, the existence of the atom, and the establishment of quantum mechanics. He predicted the existence of Bose-Einstein condensates, gravitational lensing, and gravitational waves, all of which have been confirmed. Einstein’s ideas resulted in practical applications in areas such as nuclear power, space travel, fiber optics, GPS, and computers, but his thinking has also influenced disciplines as varied as philosophy, art, and literature. It is not an overstatement to assert that this individual changed the world. As we stand in awe admiring Einstein’s accomplishments, we wonder where all that came from. Ideas, inspiration, and creativity are attributes that we associate with one organ in the body: the brain. Therefore, if Einstein was able to think all of these things up, but most other human beings are incapable of such feats, it follows that there must be something special about Einstein’s brain: something that differentiates it from the brain of common individuals, something that makes him vastly smarter. The reasoning then goes: if we find that something, that difference between Einstein’s brain and the brain of common folk, we will have found the nature of genius, the seat of intelligence.  Einstein's Brain Einstein's Brain Einstein may have been curious about the above line of reasoning, but there is one thing we know for certain: he was aware of his fame, and he did not want to be idolized after his death. He left instructions that his body be cremated and his ashes scattered. However, when Einstein died in 1955, the temptation was too much for the Princeton Hospital pathologist that performed the autopsy; Thomas Harvey. Going against the wishes of Einstein’s family, Harvey removed Einstein’s brain. When the family found out, there was some acrimony, but Harvey managed to obtain permission from Einstein’s oldest son to keep the brain as long as it was used for scientific studies. When the hospital administrator found out what he did, Harvey was fired. He went on to practice medicine but eventually was not able to renew his medical license. His marriage ended in divorce, and he ended up working on the assembly line of a plastics factory to pay his bills. Harvey took pictures and measurements of Einstein’s brain, and he had parts of the brain sectioned into many pieces that were treated with dyes and sealed in slides. Over the span of decades, he tried to get scientists interested in looking at the brain, but found few takers. He sent slides to several eminent scientists, but they found nothing out of the ordinary. Eventually, a few scientists became interested enough to perform detailed studies of the morphology of the brain using the slides and photos of the intact brain that Harvey had taken, and some differences were found when comparing Einstein’s brain to those of regular people. However, whether these differences are related to Einstein’s intellectual prowess, or whether they are part of normal brain to brain variation that can be encountered among individuals, is still an open question. There is the possibility that genius is not correlated with an obvious gross morphological characteristic of brains, but rather to the more subtle ways in which its billions of neurons are interconnected. There is also the possibility that genius resides in the temporal and spatial pattern in which the neurons interact with each other. If this is the case, it is likely that nothing can be learned about genius from fixed dead brains, as only detailed imaging of living brains will reveal their secrets. Today, the physiological roots of intelligence and genius remain as elusive as ever. And perhaps that is a good thing. Since human beings began to study the brain, we have woven fanciful explanations as to the nature of intelligence. First brain size was the metric that was thought to be related to intelligence. Thus, when evidence was produced that some races had different brain sizes than others, this became the linchpin of ideas regarding the superiority and inferiority of these races. When the idea that brain size among normal human beings was correlated to intelligence fell into disrepute, we developed the idea that we could test for intelligence and reduce it to a number. Then soon enough evidence was generated that some races, or social classes, or groups of people, did better on intelligence tests than others, again leading to notions of superiority and inferiority. The eugenics movement arose in the early twentieth century advocating the betterment of the intellectual level of society. In the United States, terms like “feeble-minded” and “moron” were developed to denote people who scored poorly on intelligence tests. The eugenics craze in the United States led to restrictions on immigration and forced sterilizations of tens of thousands of people, which invariably affected to a greater extent those who were poor, uneducated, and from minority groups. All these terrible ideas are discredited nowadays, at least academically, but watered down versions of these ideas still linger among the general public and some scholars. Asking questions about what made Einstein extremely intelligent are legitimate. But my fear is that if we do discover some characteristic in the brain responsible for genius, let’s call it “X”, we will again travel down this well-worn step by step path: 1) “X” made Einstein a genius. 2) Therefore, the more of “X” you have, the more intelligent you are. 3) We can classify otherwise normal individuals into whether they are more or less intelligent based of the amount of “X” they have. 4) Groups of people displaying lower levels of “X” are dumber. 5) Groups of people displaying lower levels of “X” are inferior. 6) Allowing these groups of people with less “X” to breed or to come to our country will compromise our society. 7) We must do something about it. A while ago I did something that Einstein would have disapproved of. I went to the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. As part of what they call “Brain Awareness Week” they had an exhibition on Einstein’s Brain. The museum has a set of slides made from Einstein’s brain that Harvey’s estate donated after Harvey died, and some of them were on exhibit. So I took a picture (see below). This section of Einstein’s brain was stained for myelin, the protein that ensheaths the axons of neurons. The black area is the fiber tracks (the white matter in the brain), and the brown area is where the neuronal cell bodies reside (grey matter). There is (or was) something in sections like these that made possible the thinking of ideas that no one had ever thought before, revolutionizing our view of reality, and changing our world forever. What is or was that something? And if we ever discover it, what will we do with that knowledge? The photograph of Albert Einstein by Orren Jack Turner obtained from the Library of Congress is in the public domain. The image of Einstein’s brain was cropped and modified from the article: Falk, Dean, Frederick E. Lepore, and Adrianne Noe. "The cerebral cortex of Albert Einstein: a description and preliminary analysis of unpublished photographs." Brain 136.4 (2012): 1304-1327, and is used here under a NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) license. The image of the section of Einstein’s brain is by the author and can only be used with permission. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed