|

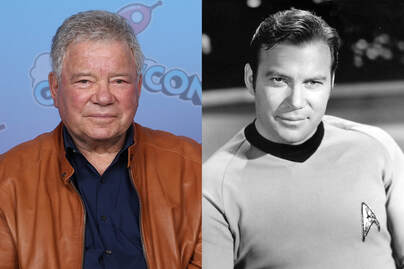

10/9/2023 The Earth or the Stars? The Contrasting Views of William Shatner and Captain James T. KirkRead Now William Shatner and James T. Kirk William Shatner and James T. Kirk In 2021, at the ripe age of 90 years, William Shatner, who played Captain James T. Kirk in Star Trek the Original Series, boarded the Blue Origin Space Shuttle with 3 other passengers and launched into space. The spacecraft followed a suborbital path that allowed its occupants to experience weightlessness and view the Earth for a few minutes before reentry. This experience profoundly affected Shatner. He says that he was expecting that going into space would be the next step to understanding the harmony of the universe and the connection between all living things. Instead, he experienced a profound grief — as if he was attending a funeral. This was because when he looked away from the warm colors and beauty of the Earth teeming with life towards space, he just saw death everywhere. Space was a black, cold, vast emptiness that stood in stark contrast to the thin layer of atmosphere that we inhabit on our planet. What Shatner felt is not new. In fact, it has been felt by so many people travelling into space that it was given a name in 1987 by writer Frank White who christened it the “Overview Effect”. This effect causes a shift in the way people see the world. They no longer see countries but rather only a group of human beings living in one world floating in the void of space. They see life on our planet as interconnected and fragile, and in need of being preserved and protected from the damage we are causing to it. After decades of playing a character that would board a starship and boldly go off towards the final frontier, Shatner realized that he had gotten it wrong. The beauty is not up there but down here, and we should devote ourselves to our planet and each other. If you have been reading my blog, you can probably figure out that I agree with Shatner. We have to protect our planet. For example, we have to transition to green sources of fuels to deal with global warming, and we have to address the harm we are causing the environment by dumping waste such as plastics into our oceans. However, I disagree with Shatner in one very important aspect. The future of humanity is not on Earth. Our future lies in the stars, and we should waste no time in figuring out how to get there. Why would this be? Let me explain. The future of the Earth is to be destroyed by the sun. Our sun is halfway through its life cycle in which it fuses hydrogen to helium, producing the heat that we all feel during the day. Eventually the amount of hydrogen will decrease to a point that the sun will begin fusing helium to heavier elements, but this will mean that our sun will expand outward and become much hotter turning into a red giant. This expansion will basically fry the Earth, boiling our oceans, and scorching our continents. And what I have just described will take place in 5 billion years. However, in practice, our planet will become inhabitable due to other effects of the sun nearing the end of its life cycle such as deoxygenation due to increased solar flux. So the time we have left on Earth is really about 1 billion years or so. Now you are probably frowning or rolling your eyes. One billion years is a really long, long time. By then, if we have not ruined our planet, our descendants will have figured out a way to move away from Earth. Why should we worry? Consider the following. The furthest object that humanity has sent into space is the Voyager 1 probe. This probe is currently travelling at the hefty speed of 35,000 miles per hour, and it was launched 46 years ago in 1977. During that time, it has covered a distance of 14.5 billion miles, which is 21.6 light hours (a light hour is the distance light travels in an hour). How far away is the nearest star to Earth? The nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is 4.24 light years away, which is 37,168 light hours. This means that in 46 years Voyager 1 has only covered 0.06% of the distance to the nearest star! We currently have no way of covering the humongously ginormous vast distances of interstellar space in any reasonable amount of time. But it’s not enough to just travel to the nearest star. We need a new planet to settle in. As an approach to identifying a possible planet to colonize (an exoplanet), astronomers try to figure out whether the planet is a rocky world (as opposed to a planet made out of gas such as Jupiter) and whether it lies in the “habitable zone” of a star. This is the zone where water can exist in liquid form. Proxima Centauri has a planet in this zone but it’s probably so close to its star that it receives lethal levels of ultraviolet radiation making it unsuitable for human life. Other planets that astronomers have found in the habitable zone are orbiting stars that are dozens to thousands of light years away from Earth. Of course, even if we find one such planet, there are myriad of other issues to resolve such as whether the atmosphere will be breathable, whether there is indigenous life compatible with our presence ranging from microbes to an intelligent species that will not want us there, etc. Finally, also consider that I have not addressed other problems such as the long-term effects of space travel on the human body. To me the solution of these problems seems daunting and may require an enormous amount of time. However, you can argue that using science and technology we will find a way much in the same way that we have solved other problems that in the past seemed unsolvable. This may well be so, but at the moment all we have is uncertainty. So, I agree with William Shatner that we must focus on our planet and deal with important issues such as global warming, global warming denial, habitat destruction, pollution, and other things. But we must not forget that, however long, our time on this world is finite. So in that sense, I agree with Captain James T. Kirk that we must boldly go where no one else has gone before. We must begin planning our trek to the stars because that is where our long-term future lies. Shatner describes his experience in his book: Boldly Go. The captain Kirk photograph by NBC Television is in the public domain. The William Shatner photograph by Super Festivals is used here under an Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

0 Comments

The distinguishing characteristic of the science fiction genre is that it sets its stories in futures where there are scientific and technological advances that have greatly expanded the capabilities of humanity, as well as social changes that have altered society. But this merely describes the genre based on the settings it uses. However, what is its purpose? As it turns out, the general purpose of most science fiction is by and large no different from that of regular stories. Science fiction is often just an artifice that allows the storyteller to generate situations that produce ethical dilemmas and existential quandaries. A favorite topic in science fiction is what it means to be human. This has been explored in many science fiction settings including the epic saga of Star Trek and its many iterations. In Star Trek the Original Series, the iconic half-Vulcan half-human character of Spock, played by the late Leonard Nimoy, was constantly trying to reconcile the Vulcan devotion to logic and control of emotions with the desires of his human half. In Star Trek Next Generation, Data, the Android played by actor Brent Spiner, sought to be human. In Star Trek Voyager, the holographic doctor, played by actor Robert Picardo, aspired to have the same rights that a human being has. Another often encountered topic is the dichotomy between being an individual and being part of a society (of which the Borg are a recurring case in Star Trek), and what life is and whether it is morally right to extinguish it. A great example of the latter plot device in Start Trek Voyager, is an episode where two crewmen, Tuvok and Nelix are fused into one being (called Tuvix) as a result of a bizarre transporter accident. When the crew of the Enterprise finally figures out how to reverse the process, the blended character, Tuvix, decides he likes being who he is and states that separating him into the original persons would be tantamount to killing him. Should he be subjected to the process against his will? Should his desire to remain how he is be respected? Despite the merits of the above approach, these stories merely use science fiction as a means to an end, and do not exploit the full potential of the genre. Nevertheless, this approach is certainly several notches above the most common use of science fiction, which is as an excuse to pit humans against monsters or create flashy action sequences studded with spaceships, alien armies, and apocalyptic weaponry. In these settings, the futuristic backgrounds where the action takes place, the technology, and the science are often no more than an afterthought, even in many science fiction books where these topics can be examined to a greater extent than movies or series. In my opinion, science fiction is at its best when it explores science and technology in depth. I consider that this is the true purpose of science fiction, and those science fiction stories that adopt this practice as part of the storyline, which I call the Grand View of Science Fiction, are often the best ever produced in the genre. I will give you two examples.  The first example is the epic series of books set in the Hyperion universe, where the author Dan Simmons conveys one of the most magnificent and amazing visions of the future of humanity that I have ever read. The books are a tour de force in world building and they are awash with the application of scientific principles on a microscopic and macroscopic scale. One of the scientific advancements in this futuristic society is what are called “farcasters”. These are structures that employ encased black holes to bend space-time and generate gateways between different areas of a planet and between different worlds, allowing for instantaneous travel. This permits people to live in one planet and work in another one, and those who are rich enough have houses where the different rooms of the house are located in different worlds and are all connected by farcaster portals. However, one of the greatest images that endured in my mind after reading these books was that of the River Tethys. This is a river that flows across more than 200 different worlds in sections interconnected by farcaster portals! Simmons’ Hyperion books, of course, have all the requisite war, action, mystery, and intrigue along with plenty of social and religious commentary, but the exploration of concepts like the farcaster and their uses to create a multiplanetary society and shape its different cultures is one of the highlights of this series.  The second example is Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke. In the novel a huge cylindrical vessel enters the solar system and a team of astronauts is sent to intercept it and explore. They manage to enter the cylinder, and what ensues is not a battle with space monsters, but the glorious exploring of a marvelous world. Rama is a hollow cylinder with an internal diameter of 10 miles and a length of 31 miles. The curved surface of its interior has what appear to be several towns. Individuals can glide weightlessly along the central axis of Rama, but its slow rotation generates an artificial gravity which increases towards the inner surface of the cylinder. When you walk on the inner surface of Rama, the land around you bends towards the sky following the shape of the cylinder, so the land is the sky! Even more disconcerting, in the middle or Rama there is a stretch of water christened the Cylindrical Sea, which bisects the cylinder, and when you stand next to the sea you see it rise with the land on both sides following the inner surface of the cylinder and meet above you. There is of course more to the story, but the description of this inner world and the various scientific laws that govern its operation is a true feast for the imagination. Now, I do admit that I enjoy the run of the mill science fiction that’s out there. In fact, I have a collection of books and movies that cover themes ranging from the human condition to action heroes and monsters. But sometimes, when I crave for more than the exploration of ethical dilemmas or the blowing up of aliens, I turn to those works that explore the Grand View of Science Fiction. Those are the best! The figures of the book covers are copyrighted images which are used here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed