|

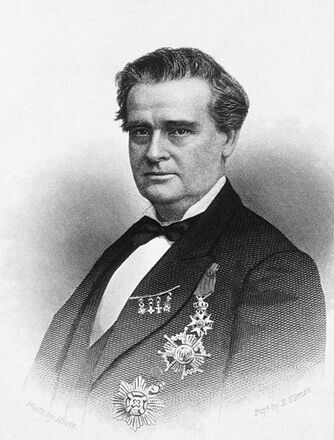

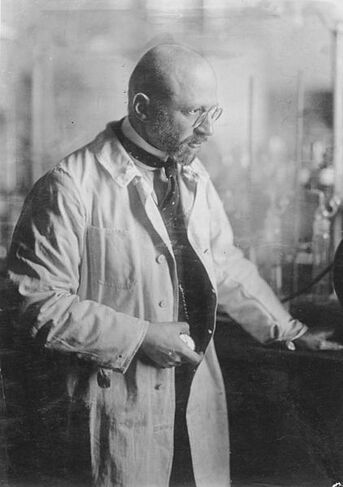

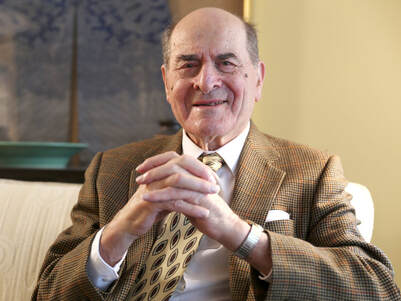

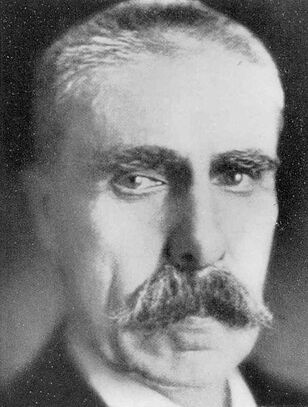

The reality behind human beings and their actions can seldom be portrayed accurately in either/or terms. However, I have repeatedly observed that a lot of people don’t really want to deal with complex realities. These people are mostly interested in stories where protagonists are sorted into tidy definable categories, such as moral or immoral, right or wrong, good or bad, heroes or villains, and infamy or glory. Due to this, individuals that can’t fit nicely into these groupings are often mythologized by writers ranging from those who are practical and create a story in order to get a point across, to those who create a story to manipulate public opinion and shape current or future events, or reinterpret the past. In this way, the special nature of the human condition with all of its intricacies and contradictions is altered to serve purposes other than the truth. Today we are going to get a glimpse of the complexity lurking behind some personalities in the fields of medicine and science.  Marion Sims Marion Sims Marion Sims was a 19th century American physician who pioneered surgical techniques and built medical devices that greatly advanced medicine. He is considered the father of modern gynecology and has had statues erected in his honor, and hospitals, universities, and schools named after him. Without a doubt Sims has benefited the lives of countless women. However there are significant blemishes in his record. For example, one of Sims’ claims to fame is the development of a surgical technique to correct a condition called vesico-vaginal fistula, where a tear in the bladder during childbirth results in a connection with the vagina leading to incontinence. Sims came up with a surgical procedure that corrected this condition, but to develop the procedure he performed many operations on slave women, and he did not use anesthesia. While he has been both attacked and defended, there is evidence that even his contemporaries were critical of his methods and deemed them unethical. William McBride was an Australian obstetrician who in 1961 was told by a nurse that a new drug he was prescribing for nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, thalidomide, was causing birth defects in newborn babies. McBride sounded the alarm in a short letter published in the medical journal, The Lancet. Other researchers and clinicians confirmed his concern. By the time thalidomide was withdrawn from the market, it had caused limb malformations in thousands of newborn children. McBride became a hero receiving multiple awards. Thalidomide became an infamous symbol of industrial greed and recklessness, and triggered the implementation of tougher drug approval laws throughout the world. Now fast forward several decades. McBride sounded another alarm, this time about a drug called Debendox (also prescribed for nausea and vomiting during pregnancy) that he found in his lab to cause birth defects in rabbits. The drug was withdrawn amid lawsuits, and McBride was a willing witness for the claimants. However, an investigation revealed that McBride falsified the data on which he based his claims. Extensive studies of Debendox found it to be safe and it was reintroduced under the brand name Diclegis . Meanwhile more research on thalidomide revealed that it is an effective drug against various cancers and other conditions, and its use has saved and improved many lives.  Fritz Haber Fritz Haber Fritz Haber was a German chemist who won the Nobel Prize in 1918 for his development of an industrial process to produce ammonia from nitrogen in the air. The ammonia thus produced could be used as a fertilizer, and this freed humanity from the dependence on natural sources of nitrogenous compounds, which increased the amount of crops that could be grown preventing famines and saving and improving the life of millions. But during World War-I, Haber had been enthusiastically involved in the German war effort that led to the manufacture and deployment of the infamous chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gases which caused hundreds of thousands of casualties and tens of thousands of deaths. Haber is recognized as the father of German chemical warfare, however being a Jew, he had to flee Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power. In the ultimate irony, Zyklon B, a chemical originally developed as a pesticide by a firm that Haber founded, was used to kill more than a million people during the holocaust including some of Haber’s relatives. The much feared mustard gas and several of its chemical derivatives were used decades after the war ended to treat cancer, a practice that gave rise to the field of chemotherapy which has saved the lives of millions of cancer patients. Peter Duesberg, is an American scientist who in 1970 discovered the first in what would eventually turn out to be a long list of cancer causing genes (today called oncogenes). The discovery of oncogenes paved the way to the connection between these genes and viruses like the Human Papilloma Virus that causes cervical cancer for which a successful vaccine was developed in 2006. Duesberg’s career was on the rise and he received numerous awards. However, when the AIDS epidemic started in the 1980s and the HIV virus was discovered as its causative agent, Duesberg questioned this fact and became very vocal. Despite being shunned by most scientists, Duesgerg’s ideas convinced the then president of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, that HIV did not cause AIDS. As a result of this Mbeki refused international help to treat the disease with drugs against the virus leading to hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths.  Henry Heimlich Henry Heimlich Henry Heimlich was an American surgeon who is famous for inventing the “Heimlich Maneuver” in 1974. This procedure to rescue people from choking has saved many lives and is taught as part of first aid courses throughout the United States. However, the Heimlich Maneuver was not accepted after a rigorous scientific evaluation of the proposed procedure, but rather because of Heimlich’s promotional talents. Despite the acceptance of the maneuver, the scientific community thought Heimlich went too far when he advocated its use for treating people having asthma attacks, expelling the mucus clogging the airwaves of patients with cystic fibrosis, and clearing water from the lungs of persons who nearly drowned. However, what thrust Heimlich into infamy was his proposal to cure Lyme disease, AIDS, and cancer by infecting patients with malaria (malariotherapy). As Heimlich was unable to find support among scientists in the United States for his idea, he raised funds from Hollywood celebrities, skirted around US regulatory agencies, and sponsored and funded several controversial and dubious clinical trials in other countries where AIDS patients were infected with malaria. In these trials a few patients died under ill-defined circumstances. No therapeutic advances resulted from this research.  Julius Wagner-Jauregg Julius Wagner-Jauregg Nevertheless, Malariotherapy was not an invention of Heimlich. It was originally conceived by Austrian physician, Julius Wagner-Jauregg who used it successfully in the era before antibiotics to treat patients with neurosyphilis. The infection with malaria would produce a fever that killed the syphilis bacterium (this is why it was also called pyrotherapy), and later the malaria would be treated with quinine. For the development of this treatment, Wagner-Jauregg received the Nobel Prize in 1927. He is considered one of the leading psychiatrists of his time and in his native Austria there are streets and hospitals named after him. Unfortunately, Wagner-Jauregg was also an anti-Semite who supported the concept of racial hygiene and advocated the forced sterilization of people who were mentally ill, criminal, or considered genetically inferior. He was an early supporter of the Nazi party and applied to join, but ironically was turned down because his first wife was Jewish. The foregoing are but a small sample of complex individuals whose actions have had a substantial impact on our world. It is easy to box these individuals exclusively in the categories of heroes or villains, but doing so is a disservice to those whom their actions directly or indirectly helped or hurt. Give these individuals their fair share of infamy and glory, but do not let their narratives become just another story. Photo of engraving by R. O'Brien of Marion Sims is by William Kurtz and is in the public domain. Photograph of Fritz Haber from the German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S13651) is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE) license. Photograph of Henry Heimlich by Nieznany is used here under an Attribution-Share-Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license. The photograph of Julius Wagner-Jauregg from Universität Graz is in the public domain.

0 Comments

|

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed