|

There are certain sayings “out there” that are repeated over and over by those who want to delegitimize science and support pseudoscience and fantastical claims. One saying that you often hear is, “Science can’t prove a negative”. What is meant by this? A “negative” is a claim expressed in negative form. So “ghosts exist” is the positive form of a claim whereas “ghosts do not exist” is the negative form of the claim. It is argued that the positive claim “ghosts exist” is provable, because all you have to do is demonstrate the existence of at least one ghost for it to be true. However, it is maintained that the claim “ghosts do not exist” is unprovable because no matter how many times you investigate the existence of an alleged ghost and come up empty handed, you will never exclude the possibility that there is a ghost somewhere.  Historical marker commemorating the Michelson-Morley experiment. Historical marker commemorating the Michelson-Morley experiment. However, science proves negatives all the time. The key to doing this is defining the characteristics of whatever it is we wish to find, and, if applicable, circumscribe its presence in space and time. Defining the characteristics of what we wish to investigate allows us to come up with a method of detection. Stating where and when what we wish to investigate should be, allows us to perform the detection at the right place and time. If we then proceed to perform the detection at the stated place and time and we find nothing, we can conclude that an entity with the specified characteristics that we looked for at the stated place and time doesn’t exist, because if it existed, we would have detected it. A famous example of this is the so called Michelson-Morley experiment. When it was determined that light had the characteristics of a wave, the question arose as to through which medium light traveled. Sound waves travel through solids, liquids, and gases as compression waves, so light was proposed to travel forming waves in a medium that was called “aether”. Two American scientists, Albert Michelson and Edward Morley, worked out how light would interact with this alleged “aether” and performed several experiments in 1887 to measure this interaction. The overall conclusion of these experiments was that the “aether” did not exist, and similar experiments conducted since then with ever increasing precision have confirmed the results. The above procedure can also be applied to things like claims for the existence of ghosts. Of course, if the proponents of the existence of ghosts and other paranormal occurrences cannot define the characteristic of the phenomena whose existence they advocate or when and where they occur with any degree of certainty, then there are serious concerns regarding whether these claims have any merits from a scientific point of view. We might as well discuss how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Here we are better served by applying Alder’s Razor (what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating). Another saying related to the one we dealt with above that is often encountered is that “The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. What is meant by this is that no matter how many times we perform tests or make observations to ascertain the existence of something such as, for example, a medical effect, if we find no evidence of its existence, we cannot conclude that it doesn’t exist. This argument is frequently made by those who advocate products and treatments of dubious value or those who are hell-bent on defending disproven propositions. The idea is that no matter how much evidence to the contrary, there MAY BE an effect that the studies may have missed. The problem with this thinking is that a carefully designed series of robust studies can be carried out to evaluate the existence of an effect of a certain magnitude. The point is not whether there is a very small effect. The point is whether there is an effect of practical importance.

For example, many people were concerned that the vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) caused autism. In response to this, scientists carried out several studies evaluating possible risks of autism as a result of vaccines which all in all included hundreds of thousands of children. No significant association between autism and this vaccine was found. Could there nevertheless be a very small effect that was not detected by the studies? Yes, but such an effect would be so small as to be of no practical importance, especially compared to the risks of unvaccinated children contracting measles, mumps, and rubella. One final saying that pops up among the pseudoscience crowd is that concerning products or therapies that have not yet been investigated. When unresearched products or therapies used by people come under criticism, their proponents argue that, “There is no evidence that they don’t work.” Thus what they are saying is that, because it has not been found to be ineffective, it is OK to keep on using it, even though this argument should cut both ways (if there is no evidence it works you should not use it). This line of reasoning essentially argues that ignorance is a valid reason to justify using a product or therapy. It treats ignorance as evidence! Even if the effectiveness of a particular product or therapy has not been investigated, there may be grounds for serious skepticism regarding its use based on other considerations. For example, if a new untested homeopathic product is introduced into the market, we would be justified in being skeptical regarding its effectiveness because the principles on which homeopathy is claimed to work violate well-established chemical laws. Additionally, the best designed studies assessing the effectiveness of existing homeopathic products have yielded negative results, so a new product will not fare any better. So to recap, science CAN prove a negative, absence of evidence CAN be evidence of absence, and ignorance IS NOT evidence. Photo of the plaque commemorating the Michelson-Morley experiment by Alan Migdall is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0).

0 Comments

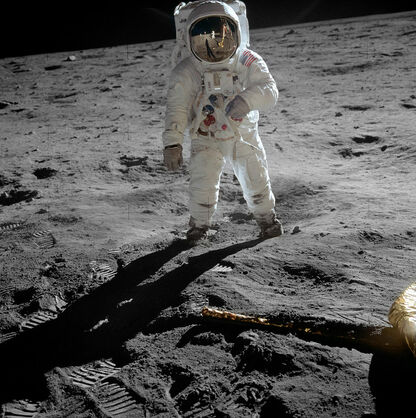

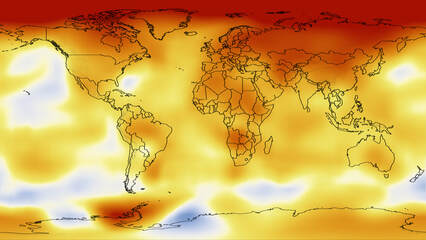

3/24/2019 Conspiracy Theorists: How to Tell the Difference between reasonable and Irrational SkepticsRead Now Terrorist attack the World Trade Center Towers Terrorist attack the World Trade Center Towers There are a lot of conspiracies out there nowadays, and many of them include scientists as the “evil guys”. Some conspiracy theorists argue that climate change isn’t real, and it’s all doctored or exaggerated data generated by scientists promoted by research funding agencies and green companies. Others argue that vaccination produces autism, and that scientists and pharmaceutical companies are trying to hide this fact. Still others argue that scientists are hiding evidence for a young Earth and the discovery of Noah’s Ark because this would confirm creationism. There are also those conspiracy theorists that state that the scientists that carried out the analyses of the destruction of the Word Trade Center by terrorist during 911 engaged in faking data and misdirection to hide the fact that the attacks were a false flag operation staged by the US government to justify the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. And there are even some who argue that the Earth is really flat, that the moon landing never happened, and that pictures of a round Earth are fake. It is tempting to roll our eyes and dismiss these conspiracy theorists as ignorant, but when you check the social media accounts of these characters and read the debates in which they become involved in public forums, you find that many of them are quite knowledgeable individuals. In fact some believers in conspiracy theories are, or have been, eminent scientists!  Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the Moon Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the Moon Conspiracy theorists and scientists share the fact that they are both skeptics, and skepticism is a healthy attitude in science. There is nothing wrong in being a skeptic, and truth be told, conspiracies should not be dismissed outright either as there have been a number of documented conspiracies. But many would argue that when it comes to some of the conspiracy theories outlined at the beginning of this post, conspiracy theorists are going too far in their skepticism and are not behaving like true scientists. So how do we differentiate between the reasonable skeptics and the irrational skeptics? How do we determine when conspiracy theorists are not behaving like true scientists? I have stated before that, unlike other disciplines, the reason that science can be right is that it can be wrong. In other words, scientific claims can be tested and proven wrong, if indeed they are. On the contrary, non-scientific claims can never be proven wrong. The proponents of non-scientific claims constantly move the goalposts and engage in fancy rationalizations to explain away the data that disprove their ideas. This is one of the characteristics of many conspiracy theorists. It is impossible to prove they are wrong, and in fact many of them when backed into a corner will argue that the mere act of trying to discredit their ideas is further proof that there is a conspiracy! It is important to identify these individuals in order to avoid getting sucked into pointless debates that will consume a lot of your valuable time. So here is the question you should ask conspiracy theorists: What evidence will convince you that you are wrong, and, if such evidence is produced, will you commit to changing your mind? If a conspiracy theorist cannot answer this question with examples of such evidence, and make the commitment to change their minds if said evidence is produced, then you can infer they are not behaving scientifically. This is one of the differences between a reasonable skeptic and an irrational skeptic.  Warming World Warming World There is another big difference between reasonable skeptics and irrational skeptics. Most conspiracy theorists are individuals who are perfectly comfortable with sitting smugly in their corner of the internet engaged in ranting out against their favorite targets to their captive audiences, but do nothing to settle the issue. Reasonable skeptics, on the other hand, do something about it. I have already mentioned in my blog the case of Dr. Richard Muller, a global warning skeptic who decided to check the data for himself. He got funding, assembled a star team of scientists (one of them would go on to win a Nobel Prize), and reexamined the global warming data in their own terms with their own methods. He concluded that indeed the planet was warming and that human activity was very likely to be the cause. This is the way rational skeptics behave. Why don’t proponents of the flat Earth theory band together, raise money, and send a weather balloon with a camera up into the atmosphere, or finance an expedition to cross the poles? Why doesn’t the anti-vaccine crowd fund a competent study to assess the safety of vaccines? Why don’t those that argue that scientists are hiding evidence of a young Earth finance an investigation employing valid methods to figure out the age of rocks? Why don’t 911 conspiracy theorists finance a believable attempt to try to model the pattern of collapse of the Word Trade Center buildings according to evidence? The answer is very simple, and it is the reason why fellow global warming skeptics repudiated the results of Dr. Richard Muller when he confirmed global warming is real. It’s because for the irrational skeptic, truth is a secondary consideration. Irrational skeptics are so vested in their beliefs and/or ideas that their main priority is to uphold their point of view by whatever means necessary. No fact or argument will sway them, no research or investigation is necessary. Because of this, when it comes to these characters, the best course of action is to apply Aldler’s Razor (also called Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword) which states that what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating. The World Trade Center photograph by Michael Foran is used here under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. Photo of Buzz Aldrin by Neil by Armstrong, both from the NASA Apollo 11 mission to the moon, is in the public domain. The image of a 5-year average (2005-2009) global temperature change relative to the 1951-1980 mean temperature was produced by scientists at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and is in the public domain.  When people say or write things like “nothing is impossible”, they normally mean this as a motivational slogan intended to overcome life’s difficulties. They don’t literally believe that nothing is impossible, but rather that talent, focus, hard work, and dedication can overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieve success. And you know what? I’m fine with that. It may not be accurate, but I understand that people may need a little oomph in their lives. If some accuracy needs to be sacrificed to help people succeed, I am willing to look the other way, so to speak. However, some people actually believe that the maxim “nothing is impossible” is true, and not only in the realm of personal achievements, but also in the field of science. I have had a few discussions with these mystics that left me wishing that I had applied Alder’s Razor. I have tried to explain that our world functions based on a set of rules that clearly delineate what is and what isn’t possible, and that science is in the business of finding what these rules are. In response to this, I normally get a list of things that scientist thought to be impossible that were later demonstrated to be possible, along with comments like “scientific theories have been proven false again and again” and some interspersed subtle and not so subtle hints that my mind is not sufficiently open. To these criticisms, I answer that science sometimes moves forward by trial and error, and, like these critics point out, scientists have made mistakes or have underestimated the complexity of the phenomena they were studying. But, as more knowledge was generated and explanations were refined, sufficiently developed scientific theories were established that allowed accurate discrimination of the possible from the impossible. Additionally, I have already pointed out not only that the vast majority of scientific theories have not been proven false, but that there are dangers in keeping your mind too open.

Nevertheless, the more important point, that seems to be ignored by the “nothing is impossible” crowd, is that our very lives depend on knowing what is possible and impossible in the world around us. Think about it. When we walk on a cement surface, we know that it will not suddenly turn into quicksand and swallow us up. When we approach a tree, we know it will not suddenly uproot itself and attack us. When a cloud passes over us, we know it will not suddenly turn to lead, fall, and crush us. We have a very clear understanding of how cement surfaces, trees, clouds, and myriads of other things work, and we know with absolute certainty what they can and cannot do. We know what can and cannot happen. We know what is possible and what is impossible. If this understanding of how our world works were false, our lives would be in peril. But our capacity to gain this understanding is nothing new or even limited to the human species. In nature we observe that animals also gain an understanding of how their surroundings work through individual experience and from observing other animals. They develop an understanding of what is edible and what isn’t, of what prey is safe to attack and what prey is dangerous, of what places are safe to be in and which are not, and so on. There is a rhyme and reason to this understanding that animals gain. They grasp that certain things are possible and other not, and they exploit this knowledge to negotiate the complexity of their environments and survive. The animal ancestors of humans acquired this information like other animals through their individual experience and from observing others. However, as ancient humans developed the capacity to think and communicate to an extent that was orders of magnitude higher than that of their animal kin, the knowledge they derived from experience became insufficient. There were many scary things happening in the world that they did not understand and could not control like earthquakes, storms, volcanoes, droughts, pests, and disease that could dramatically affect their lives. And there were also other things like eclipses, comets, shooting stars, or the moon acquiring a red hue that were mysterious. Ancient humans were able to formulate questions. Why did these things happen? Was there something or someone making them happen? How can I prevent bad things from happening? How can I be spared? Ignorance and fear begat superstition and the belief in the supernatural in order to allow humans to make sense of their surroundings and gain a measure of control over their existence. But then some humans started investigating how the world around them worked. They observed. They experimented. They found regularities and patterns. They asked and answered questions and made predictions based on the answers, which they then refined from experience. Science was born. And science was able to deliver explanations regarding the nature and inner workings of those scary things and those mysterious things allowing us to understand them, and in many cases control them, or at least reduce their detrimental effects on our lives. Viewed from this vantage point, science is just merely a more effective way of obtaining the information that we once obtained through experience. Knowledge of what is possible and not possible is key to our survival, and science has been the most successful way in which we gave gained this information. To those who say “nothing is impossible” I just have one word: balderdash! Image from Pixabay is free for commercial use (Creative Commons CC0)  In this post we are going to go over the several razors available for us to use. These razors, while commonly used by philosophers and scientists, in fact are often used by regular people, sometimes without even knowing that they are using them! However, these razors have nothing to do with the removal of bodily hair. They are called razors because they allow us to deal with the complexity of the world around us by reducing (cutting) the amount of possible explanations to various phenomena. We use them to simplify our thought processes and focus on meaningful explanations without getting lost in a bog of deceiving alternatives. We will examine several of these razors and see how they can be used to deal with the amount of bilge that is often found among claims of conspiracy theories, the pseudosciences, and the paranormal. 1) Occam’s Razor. This is the most well-known of all razors. It was developed by the English philosopher William of Ockham back in the fourteenth century. This razor posits that when faced with choosing between two competing alternatives that explain a phenomenon, we should choose the simplest one. In other words, we should not make things needlessly complicated. Many conspiracy theories such as those which claim that 9/11 was a US government-supported operation or that the US never landed on the moon run afoul of this razor. The sheer number of moving parts that would have to operate just right under a mantle of secrecy to bring about the events alleged in these conspiracies is just too complicated. The simpler explanation is that there was no conspiracy.

2) Hitchens's Razor. The late author, critic, and journalist Christopher Hitchens promulgated the dictum which states that what can be asserted without evidence, can be dismissed without evidence. The implication of this razor is that the burden of proof of a claim is with the claimant. You often hear many proponents of the occurrence of paranormal events declare that these phenomena have not been disproven. By this razor’s criteria, this argument is irrelevant. If you want people to accept a claim, YOU have to prove it is true, and you had better do a very damn good job at it to be taken seriously. 3) Sagan’s Standard. The late astronomer Carl Sagan popularized this aphorism which postulates that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. This standard recognizes that not all claims are created equal. Fantastical claims which run counter to scientific laws or mountains of evidence should only be accepted upon the production of truly remarkable evidence. By the metrics of this razor, claims for psychic phenomena, faith healers, and other such things fall short of the level of proof required to accept them. 4) Alder’s Razor. The Australian mathematician Mike Alder published an essay describing this razor, although at the time he called it “Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword” (which is a cooler name). The brutal postulate of this razor (or sword) states that what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating. If you have ever had an exchange with a flat Earth proponent and regretted afterwards having lost one hour of your life, you have experienced in the flesh what Alder was talking about. 5) Popper’s Falsifiability Principle. The great philosopher of science Karl Popper coined this famous principle which states that for something to be considered scientific it must be falsifiable. What this means is that there must be a way of proving that a claim is false if it indeed is false, otherwise said claim is not scientific. And if a claim is not scientific, its truthfulness will never be settled by observation or experiment (see Alder’s Razor above). A classical feature of the thinking of those making fantastical claims is that they always move the goalposts. No possible observation or experimental result can prove them wrong. Therefore they can’t be right. On the other hand, science can be right because it can be wrong. 6) Hanlon’s Razor. This particular razor of uncertain origin deals with the motivations behind those who propose fantastical claims. It states that one should never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. While it is true that within the ranks of those who believe in and peddle fantastical claims there are many liars and cheats, this razor reminds us that there are also scores of honest individuals who are just guilty of self-delusion or who have been bamboozled into accepting and defending these claims. In a recent post I reminded my readers about the dangers of keeping one’s mind too open (i.e. it can easily be filled with trash). Well, I guarantee that if you put these razors between you and the vast vortices of irrationality and trickery that swirl about us, your mind will be spared! The image is by Horst.Burkhardt is used here under an Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed