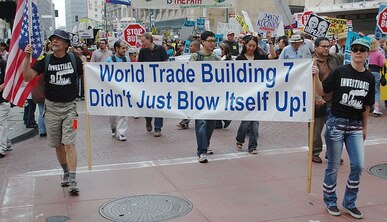

911 Conspiracy 911 Conspiracy I have often dealt in my blog with people who believe in conspiracy theories. These are individuals such as those who claim the Earth is flat and that the moon landing never happened; those who claim that the World Trade Center buildings on 911 were brought down by explosive charges and not by fires; those who claim that vaccines cause autism; those who claim that climate change isn’t real and the evidence for it is forged or altered by scientists and politicians trying to take away people’s rights and spread socialism; those who claim that the teaching of evolution is part of a conspiracy to attack religion and inject atheism into schools; or those who claim that the condensation trails left behind by flying jets are the result of the government spraying chemicals at high altitude. Why do people believe in conspiracy theories? What does science have to say about this matter? The belief in conspiracy theories has only become an important area of scientific investigation in the last two decades, but scientists have made many interesting observations and proposed hypotheses about the dynamics of the process as well as those who engage in it. The research so far indicates that, despite the great diversity of conspiracy theories, the belief in them arises as a result of the same underlying and predictable psychological processes. If an individual believes in one conspiracy theory, it is very likely that this individual will believe in other conspiracy theories even if these theories are mutually contradictory. Additionally, the belief in conspiracy theories can be greatly influenced by social context. Situations that lead to crisis in a society, such as wars, natural disasters or rapid social change, or situations that lead to individuals or groups of people feeling powerless, vulnerable, or victimized, will increase the belief in conspiracy theories.

The belief in conspiracy theories has been proposed to conform to four basic principles: 1) Belief in conspiracy theories has consequences. These consequences may be mostly negative affecting things like health, interpersonal relations, and safety of individuals or groups of individuals, but conspiracy beliefs can also fuel social change in societies, with the nature of the outcome being dependent on the type of change brought about. 2) Belief in conspiracy theories is universal. This means that belief in conspiracy theories is prevalent in all human cultures and is also found both in the present and the past. This suggests that belief in conspiracy theories is part of our biology and may have arisen through natural selection. The hypothesis has been proposed that in ancient hunter-gatherer societies, conspirational thinking was actually an advantage for individuals who faced intergroup conflict and aggression from other individuals who formed coalitions. 3) Belief in conspiracy theories is social, because it results in the upholding of a strong ingroup identity and the protection of this ingroup against some outgroup that is perceived to be hostile. It has been found that people who are likely to perceive their ingroup as superior, and to perceive outgroups as threatening, are more prone to belief in conspiracy theories. 4) Belief in conspiracy theories is emotional. Despite the fact that many conspiracy theories are underpinned by elaborate arguments, the evidence indicates that believers in conspiracy theories rely more on emotional and intuitive rather than analytical thinking. This may be the reason why belief in conspiracy theories can be triggered by strong emotional stimuli that produce anxiety, uncertainly, and feelings of lack of control. The belief in conspiracy theories has been proposed to be driven by three psychological motives: 1) Epistemic Motives: These motives involve the need to reduce uncertainty by finding explanations when information is ambiguous or lacking; the need to find meaning when faced with seemingly random events; or the need to defend beliefs when they are challenged. 2) Existential Motives: These motives involve the need for individuals or groups to feel safe and in control of their environment. 3) Social Motives: These motives involve the need to maintain a positive image of oneself or of one’s ingroup. The belief in conspiracy theories may allow the individual or the group to deal with a threat to the positive image of the self or of the group by blaming others for negative outcomes. As I explained at the beginning of this post, research into conspiracy theories is an emerging scientific field, so we need to give scientists time to gather more evidence and put to test the relevant hypotheses before we can come up with a definite theory regarding the how and why of conspiracy theories and their believers. But one of the things that I found interesting is the idea that conspirational behavior, far from being a pathology, may actually be part of our biology and may serve (or may have served) some useful purpose in our evolutionary history. This means that every one of us is capable of displaying this behavior, even without being conscious of it. Regardless of whether conspirational thinking may be a product or our biology and serve several purposes as outlined above, I would argue that in the cases where conspiracy theories do not match reality (which is the majority), the long-term effects of leading a life divorced from said reality cannot be positive. I believe this is especially true nowadays in the age of the internet when believers in conspiracy theories band together and form networks of like-minded individuals with their own websites, and chatrooms. Such groups are easily identifiable by those who want to infiltrate their communities and exploit them. Believers in conspiracy theories tend to view with distrust people like me who disagree with them publicly, but I think the real threat to these groups are those who agree with them in order to prod them towards some action. I have already outlined a step by step procedure by which anyone can sell snake oil. In my opinion, believers in conspiracy theories are highly vulnerable to snake oil salesmanship. This exploitation of conspiracy theory believers by unscrupulous individuals or organizations has taken place, and will continue taking place, because conspiracy theory groups tend to insulate themselves from those who are most likely in the position to help them, which in this case are those who disagree with them. Such is the complexity of the human mind. Photograph by Damon D'Amato is used here under an Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license.

2 Comments

Isolated Tribe in the Amazon Isolated Tribe in the Amazon I have written that science can replace magical thinking, superstition, or erroneous ideas or beliefs by ever more refined and focused views of reality though observation and experiment. And this is essentially true. Science has done away with many beliefs and ideas that were not backed by facts. However, these changes rarely happen overnight, and in fact they are often met with stiff opposition. A significant number of people won’t modify their thinking based merely on piles of scientific evidence. If one of the purposes of performing science is to generate knowledge that will help people, then scientists have to take the beliefs and cultural norms of societies into account when pursuing the application of scientific knowledge. To illustrate this, let me tell you a story. A long time ago a physician friend of mine was working in the Amazon jungle. He was tasked with helping the local natives with their medical needs. At the time, an outbreak of malaria was decimating some of the local tribes. My friend told me the story of how he had traveled by boat up a river for several days and then hiked through the jungle to reach a particularly remote tribe. He contacted the tribe’s healer and explained to him that he had some medicine that could help protect the tribe against malaria, but that it was not strong enough by itself, so he needed the help of the healer. He explained that if they combined his medicine with the healer’s powers, they would be able to beat the malaria scourge that was affecting the tribe. So my friend proceeded to treat all the members of the tribe and the healer proceeded to make his potions and perform his dances and rituals, and all the individuals in the tribe affected with malaria were cured. On hearing this, I was astonished. Did my friend really think that the superstitious rituals and brews concocted by the tribe’s healer contributed or were needed at all to cure the malaria?

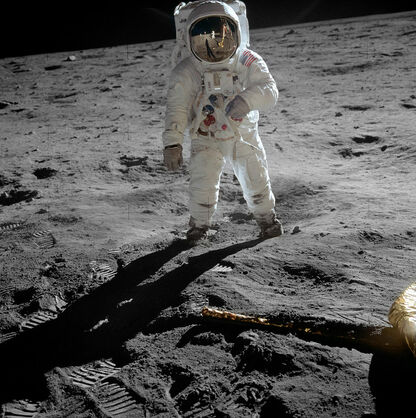

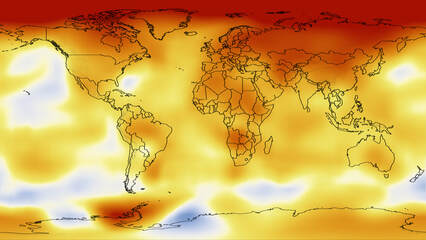

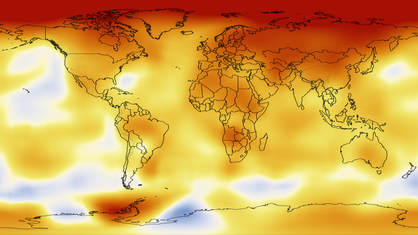

Now, let me be clear on two things. First, I agree that indigenous peoples throughout the world have developed a rich and effective arsenal of products derived from plants and animals in their environment to treat different ailments and conditions. Second, I also agree that in diseases that are self-terminating (i.e. those from which most people recover) the right psychological frame of mind can go a long way towards making individuals recover faster from their ailment. Even if a treatment is not really effective in curing a person, merely believing it is can make a difference in terms of how fast a person recovers their health. However, when it comes to certain extreme diseases, both indigenous medicine and psychology have limitations, and they cannot compete with medicines designed through evidence-based science. When I questioned my friend about these matters, he agreed with me that the healer’s traditional methods were not effective against malaria, but then he stated that that was not the issue. He explained that in tribes like the one he visited, the healer is a central figure in the hierarchy of the tribe. In the eyes of his fellow tribe members, the healer is so important in the role of protecting the tribe from dangers both real and imagined, that a healer who is perceived as ineffectual can deeply affect the psychology of the tribe and impair the way the tribe faces difficult challenges. My friend said that if he had barged right in and cured everyone, he would have delegitimized the healer in the eyes of the tribe and done a greater damage to the tribe than malaria. This is why he concocted the story about the need to combine both treatments. I was a bit shook up by this. I understood that from a practical point of view this approach made sense, but I remained ambivalent. I asked him, what about truth, facts, evidence, and reality? My friend replied that if enough people believe something no matter how preposterous, that belief for all practical purposes becomes a reality that you have to deal with if you are interested in helping out. If you go head on against these beliefs and disavow or belittle them, you will do more harm than good. I have thought about what my friend said over the years, and I believe it has some truth. People have deeply held beliefs that are often very important to them. From a scientific point of view, I may understand that some of these beliefs can be demonstrated to be false such as, for example, the belief in creationism, but I have to understand that the mere generation of more data and its repetition will not sway minds. And I think that this is a concept that should be applied (and is actually being applied) to the opposition against many of the initiatives that we need to implement today such as dealing with global warming or dealing with an increasing number of unvaccinated children. This is especially true in our current polarized environment, where scientists are portrayed by many with vested interests either as atheistic, liberal, socialist individuals who want the government to take over the lives of regular folk, or as individuals beholden to corporate interests who deliberately hide, falsify, or mischaracterize data. The success of the strategy I outlined above will depend on the approach. Very conservative and religious people will be suspicious of scientists warning them of how, unless we change our behavior, we will harm the planet. However, they may be more receptive if the focus is on the concept that humanity is the steward of creation; that we should take care of what God has created. This approach will be even more effective if it is implemented by individuals who share their own beliefs. A similar approach is also needed with people who are hesitant to vaccinate their children because they believe that vaccines cause autism. Many of these people have been swayed by stories of human suffering interpreted within the context of false or simplistic alarmist explanations. Data and facts are important in combating these false or misleading narratives, but the human side of the issue has to be addressed if scientists wish to change some minds. Scientists should acknowledge the parent’s fears and stress that the common goal of everyone is to protect children, and explain that’s why scientists vaccinate their own children. They should talk about the millions of people alive today because of vaccines, about how the world was when smallpox, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and other diseases were prevalent in our societies. Again, these arguments will be more convincing if delivered by former vaccine opponents. The human mind is very complex. Different people perceive the same reality in different ways determined by genes, experience, and culture. Some of these perceptions will not conform to the actual veridical reality that’s out there, but as explained above, this in itself constitutes a reality that must be taken into account if we truly want science to help humanity. Whether it is helping a tribe in the Amazon or getting people to go green or to vaccinate their children, science cannot operate in a vacuum. Photo by Agência de Notícias do Acre used here under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. 3/24/2019 Conspiracy Theorists: How to Tell the Difference between reasonable and Irrational SkepticsRead Now Terrorist attack the World Trade Center Towers Terrorist attack the World Trade Center Towers There are a lot of conspiracies out there nowadays, and many of them include scientists as the “evil guys”. Some conspiracy theorists argue that climate change isn’t real, and it’s all doctored or exaggerated data generated by scientists promoted by research funding agencies and green companies. Others argue that vaccination produces autism, and that scientists and pharmaceutical companies are trying to hide this fact. Still others argue that scientists are hiding evidence for a young Earth and the discovery of Noah’s Ark because this would confirm creationism. There are also those conspiracy theorists that state that the scientists that carried out the analyses of the destruction of the Word Trade Center by terrorist during 911 engaged in faking data and misdirection to hide the fact that the attacks were a false flag operation staged by the US government to justify the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. And there are even some who argue that the Earth is really flat, that the moon landing never happened, and that pictures of a round Earth are fake. It is tempting to roll our eyes and dismiss these conspiracy theorists as ignorant, but when you check the social media accounts of these characters and read the debates in which they become involved in public forums, you find that many of them are quite knowledgeable individuals. In fact some believers in conspiracy theories are, or have been, eminent scientists!  Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the Moon Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the Moon Conspiracy theorists and scientists share the fact that they are both skeptics, and skepticism is a healthy attitude in science. There is nothing wrong in being a skeptic, and truth be told, conspiracies should not be dismissed outright either as there have been a number of documented conspiracies. But many would argue that when it comes to some of the conspiracy theories outlined at the beginning of this post, conspiracy theorists are going too far in their skepticism and are not behaving like true scientists. So how do we differentiate between the reasonable skeptics and the irrational skeptics? How do we determine when conspiracy theorists are not behaving like true scientists? I have stated before that, unlike other disciplines, the reason that science can be right is that it can be wrong. In other words, scientific claims can be tested and proven wrong, if indeed they are. On the contrary, non-scientific claims can never be proven wrong. The proponents of non-scientific claims constantly move the goalposts and engage in fancy rationalizations to explain away the data that disprove their ideas. This is one of the characteristics of many conspiracy theorists. It is impossible to prove they are wrong, and in fact many of them when backed into a corner will argue that the mere act of trying to discredit their ideas is further proof that there is a conspiracy! It is important to identify these individuals in order to avoid getting sucked into pointless debates that will consume a lot of your valuable time. So here is the question you should ask conspiracy theorists: What evidence will convince you that you are wrong, and, if such evidence is produced, will you commit to changing your mind? If a conspiracy theorist cannot answer this question with examples of such evidence, and make the commitment to change their minds if said evidence is produced, then you can infer they are not behaving scientifically. This is one of the differences between a reasonable skeptic and an irrational skeptic.  Warming World Warming World There is another big difference between reasonable skeptics and irrational skeptics. Most conspiracy theorists are individuals who are perfectly comfortable with sitting smugly in their corner of the internet engaged in ranting out against their favorite targets to their captive audiences, but do nothing to settle the issue. Reasonable skeptics, on the other hand, do something about it. I have already mentioned in my blog the case of Dr. Richard Muller, a global warning skeptic who decided to check the data for himself. He got funding, assembled a star team of scientists (one of them would go on to win a Nobel Prize), and reexamined the global warming data in their own terms with their own methods. He concluded that indeed the planet was warming and that human activity was very likely to be the cause. This is the way rational skeptics behave. Why don’t proponents of the flat Earth theory band together, raise money, and send a weather balloon with a camera up into the atmosphere, or finance an expedition to cross the poles? Why doesn’t the anti-vaccine crowd fund a competent study to assess the safety of vaccines? Why don’t those that argue that scientists are hiding evidence of a young Earth finance an investigation employing valid methods to figure out the age of rocks? Why don’t 911 conspiracy theorists finance a believable attempt to try to model the pattern of collapse of the Word Trade Center buildings according to evidence? The answer is very simple, and it is the reason why fellow global warming skeptics repudiated the results of Dr. Richard Muller when he confirmed global warming is real. It’s because for the irrational skeptic, truth is a secondary consideration. Irrational skeptics are so vested in their beliefs and/or ideas that their main priority is to uphold their point of view by whatever means necessary. No fact or argument will sway them, no research or investigation is necessary. Because of this, when it comes to these characters, the best course of action is to apply Aldler’s Razor (also called Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword) which states that what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating. The World Trade Center photograph by Michael Foran is used here under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. Photo of Buzz Aldrin by Neil by Armstrong, both from the NASA Apollo 11 mission to the moon, is in the public domain. The image of a 5-year average (2005-2009) global temperature change relative to the 1951-1980 mean temperature was produced by scientists at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and is in the public domain. I have been recently reading about Flat Earthers. These are individuals who claim that the real shape of the Earth is flat. If you go to social media outlets such as Twitter and type in hashtags such as #flatearth you will see the accounts of a number of these people. One thing that struck me about Flat Earthers is that quite a number of them are sophisticated individuals who are well versed in technical jargon and can argue with you forever or outpost you on a discussion board. There is even a society called the Flat Earth Society dedicated to promoting the “truth” of the flat earth. It held the first International Flat Earth conference in 2017. But you may ask: how do Flat Earthers explain all the pictures of Earth taken from space that show it’s a sphere? The short answer: a conspiracy! Flat Earthers believe that the public is being deceived by the government which has bribed or coerced astronauts into lying, faked the moon landing, and created bogus pictures of a spherical Earth. Admittedly, the case of Flat Earthers is an extreme example. You could even say that they are at the fringe of antiscience groups such as climate change deniers, antivaxers, or creationists. But from their rhetoric, I think we can draw one valid question that is worth addressing: How do we know there is no conspiracy? The government has been shown to have lied in the past, as well as have many other institutions and organizations. How do we know they are not doing it in these cases? The answer is diversity: diversity in scientists, and diversity in methodology. I have mentioned in a previous post the famous case of N-rays, the mysterious radiation discovered by the French scientist René Blondlot, and confirmed by other French scientists, that turned out to be nothing but a case of self-delusion. During the course of the investigation of N-Rays, at one point it became evident that almost all of the positive results were coming out of French labs. When all the positive results originate from one state, or organization, or lab, we should be concerned. Diversity in the scientists that practice science is a safeguard against bias and mistakes. In another post I have also mentioned the case of polywater, a seemingly new form of water with many potential applications. Many scientists set to work on polywater and they were able to obtain the same results reported by other scientists (the results were reproducible). Nonetheless, polywater was eventually demonstrated to be false. The positive results were due to the fact that all the scientists were using the same methodology and making the same mistake! When all the positive results come from scientists using the same methodology, and these results can’t be supported by any other methods, there may be a problem. Diversity in the methodology employed in research is also a safeguard against bias and mistakes. Thus when many scientists from different nations, ethnicities, religions, political beliefs, scientific traditions, etc. study a problem employing different approaches and methodologies and come up with the same results, you can infer not only that the chance that there is a conspiracy going on is vanishingly small, but also that there is a very good chance that the theories they have generated have grasped important aspects of reality. For the conspiracy that the Flat Earthers claim to exist to be true, it would have to involve not only the government of the United States and astronauts, scientists, and private contractors involved in the space program, but also similar numbers of people in the other 5 space agencies that possess launch capabilities (those of India, Europe, China, Japan, and Russia), as well as those of the 50 plus countries that have satellites in space, not to mention individuals involved in space research in all these countries. Additionally, the roundness of the Earth has been demonstrated by many methods. If you want to argue for a flat Earth, you might as well argue that we are all living in The Matrix. However, in their conspiracy claims Flat Earthers are in good company. The theories that the global climate is warming and that humans are responsible for it, or that vaccines do not produce autism, are the product of science involving a diversity of researchers and methods, and yet they are also rejected by many people claiming that they are part of massive conspiracies. To all individuals out there espousing these conspiracy theories about science and scientists, I want to suggest that you consider a radical and revolutionary idea. This is that maybe, just maybe, the vast majority of scientists are interested in the truth, they act in good faith, and that the theories they have generated are correct! The image of a flat Earth by Trekky0623 was modified under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. The image of the real Earth from NASA is in the public domain. 3/31/2018 Moving Beyond Climate Change Skepticism and Climategate: What do we do About Global Warming Denial?Read Now In the old days scientists were considered to be individuals who were curious about the world around them. They wanted to find out how it worked, and what laws determined its behavior. They wanted to use this knowledge to make predictions, and develop technologies that could improve the situation of humankind. It was acknowledged that scientist were interested in discovering the truth. However, the social discourse in our society regarding some scientific fields that are perceived to be relevant for the culture wars has changed this view. One area where this has been very visible is global warming. There are scores of climate change skeptics who regularly pound news or social media outlets with commentary posts and videos against the notion that our planet is warming, and that humans are responsible for it. These people will not believe anyone who argues the opposite: not even one of their own! Such was the case of Dr. Richard Muller, a global warming skeptic, who decided to perform a study to check the evidence for himself. He assembled a star team of scientists (including one who won the Nobel Prize), obtained the funding, and performed the study. Dr. Muller and his team found that global warming is real, that it correlates with carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, and that human activity is very likely to be the cause. Needless to say that his results were not accepted by his fellow deniers! However, the discourse of global warming deniers goes beyond the mere rejection of the facts. What we are seeing is that scientists working in the climate field are often portrayed by many climate skeptics at best as compliant sheep who follow the consensus in the field, or at worst as despicable individuals that skew, modify, or falsify data to serve special interests, enrich themselves, gain access to funding, or promote liberal or socialist ideologies. These climate skeptics believe that if you are a scientist who agrees with the premise of global warming, then you must have some ulterior motive other than the truth, and this colors all they do. Consider the so called Climategate. In 2009 the e-mail correspondence of climate scientists at the University of East Anglia was obtained by hackers who went on to select and publish several e-mails that they claimed proved that climate scientists were manipulating data to create the impression that the world is warming. The released e-mails were pounced upon by some news (and not so news) outlets and paraded through the news cycle as proof of the conspiracy. The scandal led to investigations conducted by independent universities, committees, panels, agencies and foundations. They found the e-mails had been taken out of context and or misinterpreted by the hackers, and the scientists were cleared of wrongdoing. What had happened? Think of all the e-mails you’ve written in the past few years. Now think about someone who really doesn’t think highly of you and your beliefs. Now imagine that this person gains access to your past e-mails and pores over them trying to put together a narrative guided by their biases. I can guarantee you that, even if your e-mails contain nothing truly objectionable, this person will be able to piece together a narrative that will portray you in a less than flattering light. This is precisely what happened with the Climategate e-mails. The e-mails dealt with very technical and complex topics in an informal way, as you would expect from individuals highly knowledgeable in their field communicating and bouncing ideas off each other. The hackers did not have the scientific expertise or access to the context of the e-mails and they ended up creating a conspiracy where none existed. If the hackers and those who spread their message had paused and given scientists the benefit of the doubt, perhaps they would have avoided the debacle, but the mantra seems to be that a scientist who agrees with global warming by definition is up to no good. Despite being demonstrated to be wrong again and again, global warming skeptics and their supporters have been very successful at convincing a significant proportion of the American people that global warming is bogus. How is this possible? I believe that part of the answer lies in the fact that several possible solutions to climate change involve initiatives (e.g. reducing emission from fossil fuels), and entities (e.g. government) which many people view with suspicion. These suspicions have been purposefully stoked by powerful corporate interests that want to preserve the status quo and by organizations with social and political agendas. In essence these corporations and organizations have successfully sold snake oil to millions of individuals who, when they see scientists talk about climate change, they see the government imposing on them and taking away their jobs and their freedoms. So what are scientists to do? Perform more research? Generate more data? Attempt to educate people? Give more lectures? Continue confronting the skeptics and rebutting their arguments?  A climate scientist, Dr. Katherine Hayhoe, has an interesting suggestion. She claims that refusal to accept climate change nowadays by many people has more to do with identity and ideology than with data and facts, therefore arguing over data and facts with these people is not only futile but in fact may be counterproductive. Instead she suggests that scientists should select groups of individuals with whom they share a common value, engage with them at a personal level, explain how climate change will affect their shared value, and offer solutions they can implement. I don’t know if she is right, but her approach is a breath of fresh air in the otherwise virulent debate taking place in social media and over the airwaves. Dr. Hayhoe has produced a series of short videos entitled “Global Weirding” including the one in referenced in the link in the paragraph above where she discusses the reality of climate change and what we can do about it. The image of a 5-year average (2005-2009) global temperature change relative to the 1951-1980 mean temperature was produced by scientists at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and is in the public domain. The clip from Dr. Katharine Hayhoe’s Global Weirding video, “If I just explain the facts, they'll get it, right?”, is displayed here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use as described on Section 107 of the Copyright Act. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed