|

I am not really the explorer type. Some folks go backpacking into the wilderness for days on end. They sleep on the forest floor, cook their meals (if at all) over a fire, take care of their excretory business in the bushes, and brave ticks and other critters. Not me. I like a comfortable bed to sleep on, nice hot meals cooked on a stove or in a microwave oven, and adequate bathroom facilities. This is not to say that I don’t enjoy hiking in state or national parks, but for me these are affairs that only last a few hours, and the trails that I follow are always relatively close to civilization, which is a good thing as I sometimes get lost even on marked trails! Perhaps some people would argue that I am missing something, the type of communion with nature that can only come from getting away from it all, but I disagree. While my residence is located in good old suburbia, I also happen to live near a small lake that has a pleasant paved hiking trail around it. My neighborhood is also crisscrossed by swaths of woodland and little streams. As a result of this we have quite a rich fauna in our locality, which I have enjoyed looking at and photographing over the years. Sometimes I see an interesting bird or animal out near the lake, and sometimes I don’t even have to leave the house as they come to my bird feeders. So in this post I have decided to present the pictures I have taken over the years of some of the fauna of my neighborhood, all with their respective scientific names of course. The most ubiquitous patrons of my bird feeders are the sparrows (Passer domesticus). These noisy, opportunistic, little guys perch on the seed feeder and the suet feeder, and also roam the ground under the feeders looking for spilled seeds. I also have male and female cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) that always show up at the same time, so they may be a couple. Every now and then I get a house finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) which competes with the sparrows for perching on the seed feeder. On the other hand the white-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) doesn’t have the stomach for conflict. This nervous little bird waits until everyone else is gone, and then shows up, takes a bite out of the suet feeder or a seed out of the seed feeder, flies away, and repeats the process until it has had its fill. My suet feeder is also frequented by a downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) and by the larger red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus). As with the house finch, the sparrows often engage in inter-species conflict with the smaller woodpeckers for access to the suet feeder. In contrast the mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) stays on the ground prospecting for seeds and minds its own business. However, when the starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) turn up, everyone else flees the place. The Starlings are the hooligans of the crowd at my bird feeders. They monopolize the seed feeder, even though they can barely perch on it, and they pile onto the suet feeder and fight each other. Transitioning now to the birds of our lake, I often spot a single great blue heron (Ardea Herodias) which is often seen standing motionless near the shore. If you observe it long enough you will see it thrusting its beak with lighting speed into the water to catch fish. During the Fall and Winter months we have an itinerant population of ruddy ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis). During the winter a flock of herring gulls (Larus argentatus) also make themselves at home in our lake, whereas the robin (Turdus migratorius) is seen from spring to fall. Also from spring to fall you spot a crowd of small skittish birds that are hard to photograph (I don’t have a telephoto lens) like the red duck (Aythya americana) and the hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), which make our lake a home. I have sometimes seen red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), which are a bit of a rarity, but even rarer is to see a mute swan (Cygnus olor). In contrast Canada geese (Branta Canadensis) are a more permanent fixture of our lake, but the only birds that you find every day all year around are the mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). Among the remaining birds I’ve seen but have not managed to produce halfway decent photographs of, are coots, grebes, egrets, chickadees, canvasback and ring-necked ducks, scaups, green herons, gold finches, dark-eyed juncos, tufted titmice, blue jays, wrens, hawks, and strangely enough, crows. For several years there was a fallen tree sticking out into the lake that was favored by many of the mallard ducks as a place to rest and soak the sun (note the white albino duck among the flock). When the mallards were not present the turtles emerged from the lake and took over this prized spot. These snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentine) are the only reptiles I will be showing here. I have seen a snake or two, but I could never photograph them before they fled into the bushes. Moving on to mammals, I took a picture of this groundhog (Marmota monax) which had been chased by a dog up a tree. It is rare to be able to get close to a beaver (Castor Canadensis) or photograph one during the day as they are crepuscular (dawn or dusk) creatures, but the animal in the picture below didn’t seem to be doing very well, and sadly it disappeared during the winter of that year. Our lake went a few years without beavers, but they have made a comeback, as we now have an active beaver lodge. My final two pictures are one of a white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and one of a cat (Felis catus). Deer in the East Coast of the US are more abundant now due to lack of predators than they were 100 years ago, and while we don’t think of cats as wild animals, there are millions of domestic and feral cats living now in the US which altogether kill a significant number of birds and small mammals every year. I have also seen a couple of foxes, but alas, I didn’t have my camera with me. So, this is the fauna around my neighborhood. What have you seen around yours? The photographs are by the author and can be used with permission.

0 Comments

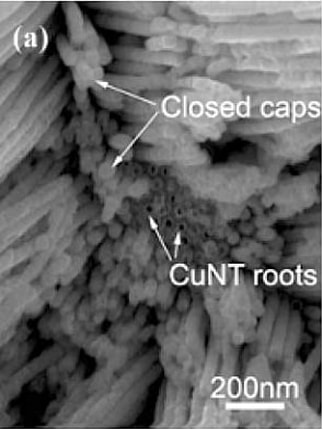

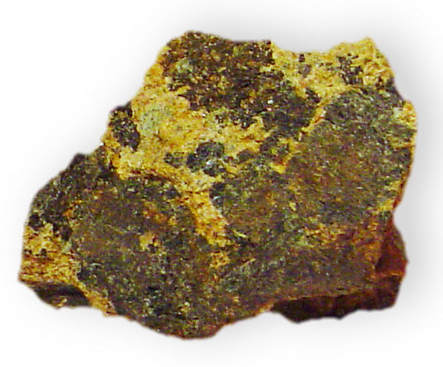

A warning to my more sensitive readers: This post contains some rude terms and juvenile humor! “Get you mind out of the gutter!” is a common exhortation used on a person who interprets things or thinks about things in indecent ways. In our culture, having your mind in the gutter is clearly considered to be something negative. However, sometimes having your mind in the gutter, or having someone around with their mind in the gutter, can actually be an advantage. How can this be? A joke in the biotech industry involves the owner of a genetics company who is thinking about the name he should give to a new branch of the company that he is planning to open in Italy. The owner innocently decides that because his company is a genetics company, and because the new branch is opening in Italy, he will call the new branch of the company "Gen-Italia". It is in situations like these where having someone around with their minds in the gutter can be useful to spot the vagaries of language and slang. The above is just a joke, but consider the true story of a company called “Custom Service Chemicals”. Back in 1964 they paid a marketing firm to suggest a new name for them. The marketing firm came up with a combination of the words “Analytical” and Technology” which perfectly described what the company was doing, and thus they changed their name to “Analytical Technologies”, which they fatefully proceeded to abbreviate to “AnalTech”. Apparently no one involved in the name-change operation had their mind in the gutter to spot the obvious problem with the new name. As a result of this, the company has been the butt of jokes (get it?) for all of its existence culminating in one memorable episode in 2017 when newspapers reported that a truck had plowed into AnalTech creating a hole which released an odor that led to a HazMat situation. The company has sometimes complained about the puerile humor it is subject to, but they get no sympathy from me!  Oh no you don't! Oh no you don't! However, the AnalTech story is nothing compared to the fiasco that beset no other than the company Pfizer. Pfizer is a pharmaceutical giant with 90,000 employees selling products in 90 international markets and generating billions of dollars in profits. This is the company that brought us penicillin and Viagra. Pfizer normally functions like a well-oiled machine when it comes to advertising their drugs, but in 2012 they experienced a major breakdown. At the time Pfizer had come up with a drug for osteoarthritis in dogs called Rimadyl, and they wanted to put together a marketing campaign to promote it. Unfortunately there was no one in their marketing team with their mind in the gutter to enlighten them. Thus it was that to encourage people to use Rimadyl on their ailing dogs, they invited their customers to “rim-a-dog”; in other words, apply Rimadyl to their canine friends. Pfizer even created a long-gone website: rimadog.com. Alas, if someone had even made a cursory search of possible slang meanings of the verb “to rim” they would have averted the catastrophe. In response to the public outcry from dog lovers, Pfizer apologized and modified their marketing of Rymadyl, but it was too late. They had already left a permanent mark in the annals (sorry, couldn’t resist using that word) of botched marketing campaigns. Sometimes what happens is that the people involved in coining a problematic name are foreign individuals who are not well acquainted with American slang. The Hungarian Nobel Prize winner Albert Szent-Györgyi discovered vitamin-C and found that paprika contained large amounts of it. This was a godsend to the depressed economy of the Hungarian town of Szeged where Szent-Györgyi resided in the early 1930s. Merchants and scientists joined forces to produce and sell a paste derived from paprika which was christened “vitapric”. Sales of the paste were so good in Europe that Szent-Györgyi and his colleagues wanted to sell vitapric in the United States. Luckily for them, someone with their mind in the gutter advised them to change the name of the product!  However, a group of Chinese researchers were not that fortunate. Dachi Yang, Guowen Meng, Shuyuan Zhang, Yufeng Hao, Xiaohong An, Qing Wei, Min Yeab and Lide Zhang discovered a method to make very small tubes (nanotubes) using metals like bismuth and copper. To name their creations they used the abbreviation for the word nanotubes “NT” preceded by the chemical symbols of bismuth (Bi) and cooper (Cu). Thus they referred to bismuth nanotubes as “BiNTs”, and cooper nanotubes as “CuNTs”. But what really cemented the fame of this Chinese group for posterity was that they wrote up the results and got them published in a mainstream English language scientific journal. Thus in their paper entitled “Electrochemical synthesis of metal and semimetal nanotube–nanowire heterojunctions and their electronic transport properties” you find no less than 12 references to “BiNT/s” and 50 references to “CuNT/s”. It seems that not a single person with their mind in the gutter was involved in the process of review and editing of the paper. Adding insult to injury, the Chinese research group received the 2007 Vulture Vulgar Acronym (VULVA) award from the British technology news and opinion website The Register. Of course, it’s not always a foreigner unacquainted with English slang who dreams up these terms. In 1972 doctors Alexander Pines, Michael Gibby, and John Waugh developed a new procedure for high resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of rare isotopes and chemically dilute spins in solids. This was a significant breakthrough because up to that moment NMR could only be applied to liquids. But then the authors proceeded to name their new technique: Proton Enhanced Nuclear Induction Spectroscopy. The problem with this name is, of course, the acronym. These naughty scientists went on to publish scientific articles where the name of the technique was prominently displayed in the tittle. It seems that no reviewer or editor with their mind in the gutter caught on to the joke. For the sake of decency most scientists nowadays refer to the technique as “cross-polarization”. While the name for the NMR technique was intended, some rude acronyms may have just arisen unintentionally from names put forward by people with insufficiently dirty minds. Thus the short denomination for the enzyme argininosuccinate synthetase is “ASS”, the cell culture substrate poly-L-ornithine is abbreviated as “PORN”, and the muscle relaxant and murder weapon, Suxamethonium chloride, is called “Sux”. Some scientific disciplines have certain traditions or follow some methodologies that make them prone to generating silly or rude names.  Cummingtonite Cummingtonite In geology there is a custom of naming a new mineral by adding the suffix “-ite” (a word derived from Greek meaning rock) to whatever the mineral is named after. But this tradition can create problems when there is no one around with their mind in the gutter. For example, when a new mineral made up of magnesium, iron, and silicon was found in the locality of Cummington in Massachusetts it was christened “Cummingtonite”, when a new mineral made up of calcium, silicon, and carbonate was discovered in a mine named “Fuka” in Japan, it was branded “Fukalite”, and a mineral made up of silicon and aluminum was named “Dickite” in honor of chemist Allan Brugh Dick who discovered it. In chemistry, when a new chemical compound is isolated from a plant, often the name of the particular chemical form of the compound is combined with the name of the genus or the species of the plant. The problem is that several plants do not have the most innocent of names, and there seem to be either a dearth of chemists or the people who vet these names with minds in the gutter. Thus “vaginatin” was isolated from the plant Selinum vaginatum, “erectone” was isolated from the plant Hypericum erectum, “clitoriacetal” was isolated from the plant Clitoria macrophylla, “nudic acid” isolated from the plant Tricholomo nudus, and so on.

I could go on, but from all these examples you get the idea. So next time someone is chastised for having their mind in the gutter, intervene and quote a few of these examples to make the case for the usefulness for such a mind in science! I have taken some of the examples listed in this post from Paul May’s amazing webpage “Molecules with Silly Names” and combined them with my own research. Mr. May has also written an eponymous book that can be bought on Amazon. Dog image by Calyponte used here under an Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. The image from the copper nanotube article is a screen capture used here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use. The image of Cummingtonite by Dave Dyet is in the public domain.  I published a post regarding the names taxonomists give to new organisms they discover and how these names can be flattering, witty, rude, insulting, or downright funny. As it turns out there is another crowd in the biological sciences that has been having a jolly good time naming things, and these are the scientists who study genes. And among these scientists, those who study fruit flies seems to have had the most fun. Now why on earth would someone want to study flies? To begin with, flies share about 60% of their DNA sequence with us, so many fly genes have equivalent human genes. Furthermore, flies have very short life cycles (which allows the study of several generations in a short time), they are easy and cheap to work with, and not only can fly mutants be studied to find out which genes are responsible for any alterations, but also the technology has been developed to modify, delete, or insert genes, and observe how these modifications change the anatomy, physiology, or behavior of the flies. All this has made fruit flies tremendously important in the study of human genetics. More than 100,000 research articles have been written by scientists employing these organisms as a model system, and a total of 6 Nobel prizes have been awarded to scientists who have used these insects to make key advances in several fields of science. So, not surprisingly, the fly researchers have discovered and named quite a few genes. But what do you name a gene when you discover it? More often than not, fruit fly scientists have selected gene names based on whatever the particular condition that the fly experienced upon mutation of the gene reminded them of. Let’s take a look at a few. There is a gene that when mutated in fruit flies leads to problems in the development of external genitalia in the male and female. What possible name would you have given this gene? Fruit fly scientists christened it the Ken and Barbie gene after the anatomically imprecise plastic dolls. There is a series of genes involved in the synthesis of steroid hormones in fruit flies. Mutations in these genes cause the fly embryos to develop scary-looking malformations in their exoskeleton. The names of the genes are: disembodied, phantom, shade, shadow, shroud, spook, and spookier. They are collective known as the Halloween genes. There are several genes that affect alcohol tolerance in fruit flies. One lab discovered a gene that when mutated made flies more resistant to alcohol (named Happyhour), a gene that when mutated made flies more sensitive to alcohol (named Cheapdate) and a gene which helps flies become tolerant to alcohol over time (named Hangover). Fruit flies have 8 photoreceptors in their compound eyes. Scientists discovered a gene that when mutated results in flies that lack the seventh photoreceptor in their eyes. Thus the gene was named Sevenless. Other genes that interacted with Sevenless were named in serial horror movie fashion: Bride of Sevenless (also known as BOSS), Daughter of Sevenless, and Son of Sevenless. My favorite fruit fly gene is one that when mutated doubles the fly’s lifespan. The gene was christened INDY, which is an acronym for “I’m Not Dead Yet”. This is in reference to the Bring Out Your Dead scene from the Monty Python and The Holy Grail movie. And the examples go on and on. What would you call a fly gene that when mutated results in flies with no hearts? Scientists named it, Tinman, after the character in The Wizard of Oz who did not have a heart. What would you call a fly gene that when mutated causes neurological degeneration with the production of holes in the brain? Swiss Cheese! What would you call genes that control the death of cells in flies? Grim and Reaper! But the name doesn’t have to be related to what a mutation does to the gene. For example, several fly genes code for proteins that are located in an area of the fly’s tissue cells called “the matrix”. Accordingly these genes were named Trynity, Nyobe, Morpheyus, Neyo (Neo), and Cypher after characters in the movie The Matrix. Despite the role of fruit flies in gene research, new genes have also been identified and named in other living things. For example, in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana there are two genes called Clark Kent and Superman that when mutated result in a plant with a large number of male parts (stamens) on their flowers. Interestingly, there is another gene called Kryptonite that when mutated causes the plants to lose their male parts and become sterile. A gene in the zebrafish that when mutated makes the fish extremely sensitive to light (so much so that light kills them) was christened “Dracula”. A gene in sheep that when mutated causes the animals to develop very prominent rear ends was named “Callipyge” which translates from Greek as “beautiful buttocks”. One final example is a gene in mice that codes for an enzyme that transfers a molecule of the sugar fucose to a protein. It was found that when this gene is mutated it causes the females to reject the sexual advances of the males. The name of the gene is the fucose mutarose gene, but it is better known by its acronym FucM ! Of course, as long as gene naming remained confined to insects or animals, all was fun and games. Unfortunately gene naming hit a snag. This was due on the one hand to how successful scientists were in finding counterparts of the genes of fruit flies and other animals in humans, and on the other hand to the fact that some of these genes were found to be associated with diseases.  Consider for example the gene Hedgehog. When this gene is mutated in flies, it causes the fly embryos to be covered with tiny spikes. The counterpart of this gene in mammals including humans was christened Sonic Hedgehog after Sega’s video game character Sonic The Hedgehog. It turned out that a mutation in the human Sonic Hedgehog genes produces a disease called Holoprosencephaly which causes brain, skull, and facial defects. So visualize the following situation: “I’m sorry, Mr. John and Jane Doe, your child was born with cranial and facial malformations, due to a mutation in Sonic Hedgehog. He may die from the disease, or if he survives, he may experience a certain degree of mental retardation or behavior problems and seizures. What is Sonic Hedgehog? Oh, it’s a gene named after a video game character. Ha, ha, ha, funny isn’t it?” As Sonic Hedgehog and other genes became linked to deadly or life-altering human diseases, clinicians became uncomfortable with explaining the inside jokes behind these playful but sometimes rude or insensitive names to patients and their families. Because of this the Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee consulted with many scientists and renamed several of the worst offenders. So now, for example, the committee recommends that Sonic Hedgehog be known by the acronym SHH. From all the foregoing you may derive the impression that the scientists who name these genes are foolish, but nothing could be further from the truth. These funny names represent some much needed levity in what is very hard and at times very frustrating work, and these scientists have produced key advances that have increased our knowledge of how our body works and that have also saved lives. The first drug that fights cancer by targeting the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway in cells, Vismodegib, was approved by the FDA in 2012. So next time you hear about the Moonwalker fly (a fly that walks backward when certain neurons are activated by genetic manipulations in a manner reminiscent of Michael Jackson’s famous dance move), or the Stargazer mouse (a mouse that rears its head upwards due to a mutation in a signaling gene), think about the many nights and weekends that the scientists that worked with these critters spent in the labs and give them a smile. Image of a fruit fly by Sanjay Acharya, used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0). license. Image of Sonic the Hedgehog by Chris Dorward used here under an Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. In season 2, episode 5 of that great show “The Big Bang Theory,” Penny (played by actress Kaelly Cuoco) asks Sheldon (played by actor Jim Parsons) why he didn’t get his driving license when he was 16 years old like everybody else. Sheldon, a theoretical physicist with 2 PhDs, replies that it was because he was busy “examining perturbative amplitudes in n=4 supersymmetric theories leading to a re-examination of the ultraviolet properties of multi-loop n=8 supergravity using modern twistor theory.” Of course the Big Bang Theory is just a sitcom, but the science depicted in the program is often quite accurate and also as cryptic as real science is too. Check for example actual titles of research published in scientific journals: -Vortex dynamics in two-dimensional Josephson junction arrays with asymmetrically bimodulated potential. -Dopaminergic Polymorphisms Associated with Time-on-Task Declines and Fatigue in the Psychomotor Vigilance Test. - Heavy cluster knockout reaction (16)O((12)C,2(12)C)(4)He and the nature of the (12)C-(12)C interaction potential. -Countertransference feelings in one year of individual therapy: An evaluation of the factor structure in the Feeling Word Checklist-58 And, last but not least, check a couple of sentences from an article I published recently: "There was a marked effect of DPD inhibition by EU on plasma 5-FU. Mean Cmax was nearly doubled (914.6 vs. 471.5 μM) and mean AUC values were increased 4.7-fold (819 vs. 174 nmol/ml x h) in animals treated with EU compared to control animals, confirming effective DPD inhibition in the model." With respect to the example from my article above, you may argue that one of the reasons the sentences are not understandable is because I used some abbreviations. OK, fair, what if I told you that “DPD” stands for "dehydropyrimidine dehydrogenase". Is that clearer? Regular folk are often bewildered by the apparent mumbo jumbo present in the scientific literature. Some may even wonder if all those big words are nothing more than gobbledygook employed by people who just pretend to know what they are talking about while hiding behind a wall of jargon. Why use all those complex words? Can’t scientists express themselves in a way that can be understood by mere mortals? Scientists, scientific writers, and science bloggers such as yours truly (on all 3 counts), do try to explain the complexities of science to non-scientists. However, to understand why it’s virtually impossible to avoid creating and using the technical jargon found in the scientific literature, consider the following thought experiment. Imagine that you learn the language spoken by a tribe in a remote jungle that has had no contact with civilization. Now imagine you visit this tribe, and using only the words of their language, you try to explain to them all about computers, microwave ovens, the internet, television, CDs, DVDs, cell phones, cars, airplanes, trains, refrigerators, washing machines and so forth. These terms are very familiar to you, but our degree of technological advance has led to the production or discovery of many entities that are not part of the immediate reality that this tribal language describes. If you incorporated these words into the tribal language and used them in front of the members of the tribe, they would think you are talking nonsense because the members of the tribe would have no real-world reference for these things. That is the same situation with scientists as it relates to the regular language people use. The language is just insufficient to name what scientists are discovering, therefore new terms have to be invented. As scientists discover and name more things and their field of study grows in complexity, its comprehension becomes daunting for the non-specialist. This is not to say that a few scientists may not attempt to hide their ignorance on some topics behind a wall of jargon, but when the vast majority of scientist write in the technical literature or talk with their peers, they must employ many words that are not in the common parlance. Nevertheless, in some areas these words eventually filter into the day to day reality of the common folk. Just consider words like DNA, genes, antibiotics, or vitamins. These words were once technical terms that are of common use today by non-scientists. So to sum it up, no, it’s not mumbo jumbo, and some of these seemingly incomprehensible words that you find vexing in today’s scientific literature may end up being part of the everyday vocabulary of your children or your children’s children in the future.  Felis catus Felis catus For the non-scientist scientific names can be vexing. Why in the world should a cat be called Felis catus? Have the scientists that coin these names (taxonomists) lost their marbles? What’s wrong with these people? Are they so bored that their idea of a good time is to spend endless hours dreaming up strange names? Why do they do that? If all of humanity spoke one language, taxonomy would be a simpler enterprise. The problem is that people speak hundreds of languages, and the ranges of the majority of organisms span several countries and even continents. Living things in different places are given different names. In fact, sometimes even among people that speak the same language an animal in one region is known by a different name in another. The problem is that we need to identify with accuracy organisms that are pests, or transmit disease, or produce some chemical that may be useful in medicine. Because of this need, scientists agreed on one system of classification that everyone could use regardless of their country, language, or culture. Living things are commonly referred to by the genus to which they belong followed by their species (a type of name and surname if you will), which is known as the binomial classification. These names are often (but not always) written in Latin or Greek words or Latinized words. The reason for this is mostly historical. During the beginnings of taxonomy (the science of classifying living things), Latin was the language of science and initial classifications employed Latin or Greek words. Eventually, even as the influence of Latin in science waned, because so many living things had already been classified and given Latin or Greek names, the system was retained. The majority of scientific names are made up of the Latin or Greek name of the organism and make allusions to some of its characteristics. So the cat is named Felis catus, which means cunning cat, the southern flying squirrel is named Glaucomys volans which means grey flying mouse, the mallard duck is called Anas platyrhynchos, which mean broad-snouted duck, the European polecat is named Mustela putorius which means foul-smelling weasel, and so on. Taxonomists name these organisms and then proceed to define certain characteristics that make the organism unique so they can be identified. By this metric you’d think that taxonomists have a pretty dull job. However, the actual scientific names are merely used to identify the entity. They don’t have to be logical or in any way related to a characteristic of the living thing. In fact they can be downright funny. A scientist from the Smithsonian Institution, Terry Erwin, decided to have some fun when naming new species of beetles belonging to the genus Agra. As a result of this we have Agra cadabra, Agra phobia, Agra vate, and Agra vation among others. The entomologist Gordon Marsh christened two new species of wasps Heerz lukenatcha (Here’s looking at you) and Heerz tooya (Here’s to you). Entomologist Neal Evenhuis labelled several new species of flies Pieza kake, Pieza pie, Pieza rhea, and Pieza deresistans (i.e. piece of cake, piece of pie, etc.). And there is even toilet humor! Entomologist Melville Hatch decided to name new species of round fungus beetles Colon forceps, Colon grossum, Colon horni, Colon monstrosum, and Colon rectum (do note that here “Colon” is derived from the Greek word “Kolon” meaning limb or joint).  Bugeranus carunculatus Bugeranus carunculatus A few scientific names are intentionally rude such as that coined by scientist, James Pakaluk, who seemed to be in a particularly spiteful mood when he named a beetle Foadia Pakaluk (FOAD is an acronym for F*** Off And Die), or that created by entomologist, Arnold Menke, who gave a new species of wasp the name Pison eu (hint: say it out loud). However, in many cases the scientific name sounds rude only as a result of misreading the original Latin or Greek names. An African species of wattled crane is called Bugeranus carunculatus. In English the genus of the bird sound like an elementary school insult until you realize that it is made up of the fusion of the Greek word bous, which means “ox”, and geranus, which means “crane” (hence ox-crane). The Tibetan blackbird is called Turdus maximus, but any possible scatological interpretation of this name vanishes when we understand that turdus is the Latin word for the bird we call thrush. However, Aploparaksis turdi, a tapeworm, does include in the species name a reference to the material where this living thing can be found. There are many motivations behind scientific names. In 1904 the English entomologist, George Kirkaldy, decided he would immortalize some of his romantic conquests as taxonomical names when classifying several new species of the so-called true bugs (hemiptera). So he created several new genuses: Dolichisme, Florichisme, Marichisme, Nanichisme, Peggichisme, and Polychisme (i.e. Dolly kiss me, Flori kiss me, etc.) followed by the species name “kirkaldy”. For this levity, Kirkaldy, was criticized as frivolous by the London Zoological Society, but his bug names nevertheless were retained. In 2002 Neal Evenhuis (of Pieza kake fame, see above) decided to take up this tradition by naming a fossil fly Carmenelectra shechisme in reference to the actress Carmen Electra (although he did not know her personally).  Dinohyus hollandi Dinohyus hollandi A less often seem theme in scientific names is insults levied against a person. For example, the seed bug Aphanus rolandri was named by the father of taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, after a greedy student named Daniel Rolander who refused to show Linnaeus the specimens he collected. Aphanus means ignoble or obscure. Two Swedish paleontologists, Elsa Warburg and Orvar Isberg, despised each other so much that they traded insults by naming new species. Warburg gave a trilobite the name Isbergia planifrons (planiforms means “flat forehead” which is akin to “stupid” in Swedish) and Isberg named a species of mussel Warburgia crassa (crassa meaning fat). A prehistoric hoofed-mammal that was thought to be a type of pig was named Dinohyus hollandi by paleontologist O. A. Peterson after his boss the Carnegie Museum director W.J. Holland. Holland was greatly disliked because he insisted that his name be included in every publication even if he had not contributed to it. The name of the animal means “Holland’s Terrible Pig”, which of course can be read as “Holland is a terrible pig”!  Scaptia beyonceae Scaptia beyonceae However, most of the time having a new species named after you is considered an honor. For example, former US president George Bush, former Vice President Dick Cheney, and former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had new species of slime-mold beetles of the genus Agathidium named after them by entomologists who wanted to thank them for their service. These were A. bushi, A. cheneyi, and A. rumsfeldi, respectively. The creator of the cartoon The Far Side, Gary Larson, had a new species of feather louse (Strigiphilus garylarsoni) named after him for his contributions to inserting science into the public consciousness. Nevertheless, sometimes this honor may not be for the most exalted of reasons. A species of horse fly with a prominent rear end was named Scaptia beyonceae after the voluptuous singer/songwriter Beyoncé. But you don’t even have to exist to have a species named after you! Consider a species of mushroom named Spongiforma squarepantsii after the cartoon character Spongebob Squarepants, a fossil trilobite named Han Solo after the Star Wars character, or a cave arthropod named Gollumjapyx smeagol after the character Gollum/Smeagol from The Lord of the Rings. Recently 7 new spider species were named after fictional spiders in literature ranging from Harry Potter to Charlotte’s Web. The shortest scientific names are those of a South Asian bat, Ia io, and a Chinese dinosaur, Yi qi. The longest scientific name belongs to the Southeast Asian soldier fly, Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides, which means “near soldier wasp-fly, wasp fly-like". Go figure. An even longer name, which was proposed for a crustacean from Lake Baikal, Gammaracanthuskytodermogammarus loricatobaicalensis, was thankfully invalidated by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature!  Amorphophallus titanum Amorphophallus titanum Sometimes scientific names create uncomfortable situations. In 1878 in the jungles of Sumatra Florentine naturalist Odoardo Beccari discovered the plant with the largest unbranched flower in the world. The central structure of the flower called the spadix can grow to a height of 12 feet and is one of the reasons Beccari named it Amorphophallus titanum. Little did he know that the seeds of this plant would make their way to botanical gardens all over the world where they would become sensations every time they bloom, not only because of their size, but because the flower emits a putrid smell akin to a rotting corpse meant to attract flies and carrion beetles, which are their pollinators. As a result of this, the flowerings of A.Titanum specimens attract large crowds including families with children. This has created a “nomenclature problem”. What name do you call this plant? Do you really want to use the scientific name only to have to deal with a little child raising their hand and asking, “What is an “amorfofalus”? To avoid this, the naturalist Sir David Attenborough (who incidentally has a large number of creatures named after him) coined the term “Titan Arum”, which is now often used to describe the plant in public. I could go on and on, but you get the idea. The field of taxonomy has a rich history replete with anecdotes, inside jokes, and witty and flamboyant personalities. The work of taxonomists is important, and despite their obsession with research and the classification of living things, many of these individuals who spend countless hours in the field and the lab are having a good time. Remember this next time you read that a fossil amphibian was named Eucritta melanolimnetes (Creature from the Black Lagoon), that a bacterium that survived exposure to outer space was named Halorubrum chaoviator (traveler of the void), or that a squid-like creature was named Vampyroteuthis infernalis (vampire squid from hell)! Do you have a favorite scientific name? Write a comment and let me know. Cat picture by Tiki toko used under a creative commons attribution-share alike 4.0 international license. Picture of a wattled crane at Dallas Zoo by kusanagi seed used under a creative commons attribution-share alike 2.0 generic license. Picture of Dinohyus hollandi is from the University of Nebraska State Museum. Photo of Scaptia beyonceae by Erick used under a creative commons attribution-share alike 3.0 unported license. Photo of Titan Arum by Lothar Grünz is in the public domain. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed