I published a post regarding the names taxonomists give to new organisms they discover and how these names can be flattering, witty, rude, insulting, or downright funny. As it turns out there is another crowd in the biological sciences that has been having a jolly good time naming things, and these are the scientists who study genes. And among these scientists, those who study fruit flies seems to have had the most fun. Now why on earth would someone want to study flies? To begin with, flies share about 60% of their DNA sequence with us, so many fly genes have equivalent human genes. Furthermore, flies have very short life cycles (which allows the study of several generations in a short time), they are easy and cheap to work with, and not only can fly mutants be studied to find out which genes are responsible for any alterations, but also the technology has been developed to modify, delete, or insert genes, and observe how these modifications change the anatomy, physiology, or behavior of the flies. All this has made fruit flies tremendously important in the study of human genetics. More than 100,000 research articles have been written by scientists employing these organisms as a model system, and a total of 6 Nobel prizes have been awarded to scientists who have used these insects to make key advances in several fields of science. So, not surprisingly, the fly researchers have discovered and named quite a few genes. But what do you name a gene when you discover it? More often than not, fruit fly scientists have selected gene names based on whatever the particular condition that the fly experienced upon mutation of the gene reminded them of. Let’s take a look at a few. There is a gene that when mutated in fruit flies leads to problems in the development of external genitalia in the male and female. What possible name would you have given this gene? Fruit fly scientists christened it the Ken and Barbie gene after the anatomically imprecise plastic dolls. There is a series of genes involved in the synthesis of steroid hormones in fruit flies. Mutations in these genes cause the fly embryos to develop scary-looking malformations in their exoskeleton. The names of the genes are: disembodied, phantom, shade, shadow, shroud, spook, and spookier. They are collective known as the Halloween genes. There are several genes that affect alcohol tolerance in fruit flies. One lab discovered a gene that when mutated made flies more resistant to alcohol (named Happyhour), a gene that when mutated made flies more sensitive to alcohol (named Cheapdate) and a gene which helps flies become tolerant to alcohol over time (named Hangover). Fruit flies have 8 photoreceptors in their compound eyes. Scientists discovered a gene that when mutated results in flies that lack the seventh photoreceptor in their eyes. Thus the gene was named Sevenless. Other genes that interacted with Sevenless were named in serial horror movie fashion: Bride of Sevenless (also known as BOSS), Daughter of Sevenless, and Son of Sevenless. My favorite fruit fly gene is one that when mutated doubles the fly’s lifespan. The gene was christened INDY, which is an acronym for “I’m Not Dead Yet”. This is in reference to the Bring Out Your Dead scene from the Monty Python and The Holy Grail movie. And the examples go on and on. What would you call a fly gene that when mutated results in flies with no hearts? Scientists named it, Tinman, after the character in The Wizard of Oz who did not have a heart. What would you call a fly gene that when mutated causes neurological degeneration with the production of holes in the brain? Swiss Cheese! What would you call genes that control the death of cells in flies? Grim and Reaper! But the name doesn’t have to be related to what a mutation does to the gene. For example, several fly genes code for proteins that are located in an area of the fly’s tissue cells called “the matrix”. Accordingly these genes were named Trynity, Nyobe, Morpheyus, Neyo (Neo), and Cypher after characters in the movie The Matrix. Despite the role of fruit flies in gene research, new genes have also been identified and named in other living things. For example, in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana there are two genes called Clark Kent and Superman that when mutated result in a plant with a large number of male parts (stamens) on their flowers. Interestingly, there is another gene called Kryptonite that when mutated causes the plants to lose their male parts and become sterile. A gene in the zebrafish that when mutated makes the fish extremely sensitive to light (so much so that light kills them) was christened “Dracula”. A gene in sheep that when mutated causes the animals to develop very prominent rear ends was named “Callipyge” which translates from Greek as “beautiful buttocks”. One final example is a gene in mice that codes for an enzyme that transfers a molecule of the sugar fucose to a protein. It was found that when this gene is mutated it causes the females to reject the sexual advances of the males. The name of the gene is the fucose mutarose gene, but it is better known by its acronym FucM ! Of course, as long as gene naming remained confined to insects or animals, all was fun and games. Unfortunately gene naming hit a snag. This was due on the one hand to how successful scientists were in finding counterparts of the genes of fruit flies and other animals in humans, and on the other hand to the fact that some of these genes were found to be associated with diseases.  Consider for example the gene Hedgehog. When this gene is mutated in flies, it causes the fly embryos to be covered with tiny spikes. The counterpart of this gene in mammals including humans was christened Sonic Hedgehog after Sega’s video game character Sonic The Hedgehog. It turned out that a mutation in the human Sonic Hedgehog genes produces a disease called Holoprosencephaly which causes brain, skull, and facial defects. So visualize the following situation: “I’m sorry, Mr. John and Jane Doe, your child was born with cranial and facial malformations, due to a mutation in Sonic Hedgehog. He may die from the disease, or if he survives, he may experience a certain degree of mental retardation or behavior problems and seizures. What is Sonic Hedgehog? Oh, it’s a gene named after a video game character. Ha, ha, ha, funny isn’t it?” As Sonic Hedgehog and other genes became linked to deadly or life-altering human diseases, clinicians became uncomfortable with explaining the inside jokes behind these playful but sometimes rude or insensitive names to patients and their families. Because of this the Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee consulted with many scientists and renamed several of the worst offenders. So now, for example, the committee recommends that Sonic Hedgehog be known by the acronym SHH. From all the foregoing you may derive the impression that the scientists who name these genes are foolish, but nothing could be further from the truth. These funny names represent some much needed levity in what is very hard and at times very frustrating work, and these scientists have produced key advances that have increased our knowledge of how our body works and that have also saved lives. The first drug that fights cancer by targeting the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway in cells, Vismodegib, was approved by the FDA in 2012. So next time you hear about the Moonwalker fly (a fly that walks backward when certain neurons are activated by genetic manipulations in a manner reminiscent of Michael Jackson’s famous dance move), or the Stargazer mouse (a mouse that rears its head upwards due to a mutation in a signaling gene), think about the many nights and weekends that the scientists that worked with these critters spent in the labs and give them a smile. Image of a fruit fly by Sanjay Acharya, used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0). license. Image of Sonic the Hedgehog by Chris Dorward used here under an Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license.

0 Comments

In case you don’t follow rock climbing as a sport, you should know that last year the “moon landing” of rock climbing happened: Alex Honnold Free-soloed El Capitan in Yosemite! In case you don’t know what this means, let me break it down for you. El Capitan This is a massive granite monolith in Yosemite national park in California that rises vertically from the floor of Yosemite Valley a distance of almost 3000 feet. It is considered one of the ultimate big-wall climbs in the world, and is a central part of a rock climbing culture in the US replete with wild anecdotes, traditions, and larger than life characters. Free soloing There are several styles of rock climbing. Most climbers making their way up very difficult walls insert gear in the cracks in the rock and attach ropes to the gear in order to hoist themselves up. Some of the best climbers in the world often use a style called Free Climbing where they just use their hands and feet to climb the wall and employ gear and ropes only for protection in case of a fall. Free soloing is the most dangerous variety of climbing. In free soloing, climbers free-climb the rock but without using any gear or ropes for protection. If they make a mistake, they fall and die.  Alex Honnold Alex Honnold is a US rock climber who specializes in free solo climbing, and who has dazzled the world with some of the most daring big wall climbs ever attempted by a human being, all without a rope to hold him in case he falls. So, put the three above together. Yes, Alex Honnold climbed the massive hulk of El Capitan using no ropes for protection in case of a fall. Any distraction, any slip, or any handhold or foothold that broke apart would have sent him careening towards the valley floor below. If you want to get an idea of what it means to climb El Capitan you can check out the following Google Maps link. But why am I writing about rock climbing if this is a science blog? The reason is the following.

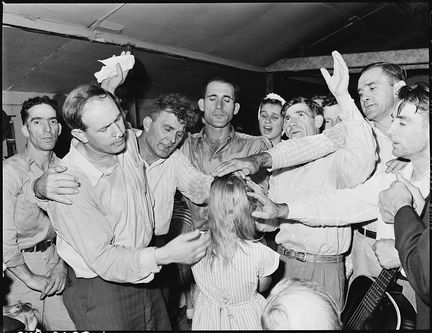

From what I have described above you would think that Alex Honnold is the best climber in the world, right? Actually, this is not true, and even he admits it. Of course, there is no doubt that Alex is an elite climber, among the best in the world, but there are many other climbers that are technically more gifted and stronger than Alex when it comes to climbing. Any of these climbers can climb what Alex climbs and then some (but here is the key distinction) as long as they are protected by a rope. Place any of these climbers thousands of feet above the ground on a vertical rock face with nothing to prevent them from falling, and they will be unable to climb stretches of rock that they would have normally strolled over. They would likely panic and fall to their deaths. This is where Alex excels above all rock climbers in the world: he is able to control fear and focus on the climb. The late Dean Potter, who was also a free soloist, best described this challenge when he was trying to walk a tightrope in Yosemite. Potter said that if he suspended the rope a few feet above the ground, he had no problem in crossing it. However, when he suspended exactly the same stretch of rope thousands of feet above the valley floor he would often fall when trying to cross it. He correctly deduced that success in walking the rope depended on the mind, and after a few tries with a safety harness he was able to successfully accomplish this feat unprotected several times. When rock climbers are exposed to situations where they deal with increased risk, their stress hormone levels and anxiety are increased. It is in these situations that an area of the brain called the amygdala, which is involved in the production of the sensation of fear, is activated. Moderate activation of the amygdala is often a good thing. There are people with a condition called Urbach-Wieth Disease where the amygdala becomes calcified and ceases to work. As a result of this, these people can’t experience fear, and this is a big problem in their lives. Fear is a healthy response to many things, and it keeps us away from danger. However, overactivation of the amygdala can lead to panic, and loss of control and capacity for rational thought. Most rock climbers will tell you that the best place to panic is not while clinging to a near vertical section of a rock wall on tiny handholds and footholds thousands of feet above the ground. Some neuroscientists became interested in Alex and convinced him to allow them to perform an experiment. The scientists viewed his brain with magnetic resonance imaging while he was being shown a series of ghastly images designed to activate a normal person’s amygdala. As a control the scientists also imaged the brain of another rock climber. The results indicated that although Alex does have an amygdala in his brain, it was not activated by the images. However, the amygdala of the control climber lit up as expected. The scientists speculated that either Alex’s amygdala doesn’t activate normally, or other brain regions are able to inhibit its activation. Alex rejects the notions that he doesn’t experience fear while rock climbing without a rope for protection. Nevertheless, he claims that he can just put it aside without allowing it to get in the way of focusing on the climb. This ability is key for achieving what he has done. His free-solo of El Capitan required him to maintain his concentration for almost 4 hours of climbing. This allowed him to accomplish the feat without a single mistake, which was vital as only one mistake could have gotten him killed. The above not only highlights how the differences in wiring in our brains can make us experience the reality around us in very different ways, but also the role that emotions such as fear can have in our life. Fear is, of course, not only restricted to rock climbing. Will I develop a serious health problem? Does so and so love me? Are my children safe? Will I get mugged? Will I keep my job? Should I get involved in this business? Will my economic situation improve? What will the president tweet next? Uncertainty about these and many other situations can generate anxiety, stress, and fear of different levels of intensity, some of which can produce inappropriate responses that will hurt rather than help us. Fear and stress can also cause alterations in the wiring of the brain that can affect our behavior even when the events that triggered the fear are not present anymore such as in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This is why the study of fear and related phenomena is an active area of research in the biological and psychological sciences. Going back to Alex, his climb of El Capitan will be featured in a National Geographic movie (yes, it was filmed!) entitled, Free Solo, that will be released this fall on select theaters. Alex has also written a book, Alone on a Wall, where he details his many climbing exploits before his monumental El Capitan climb. Note: the film about Alex's free solo climb won an Oscar for best documentary. El Capitan image by Mike Murphy is used here under an Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. The image from Alex’s website is displayed here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use as described on Section 107 of the Copyright Act.  In a past post, I wrote about how it is not in the nature of science to analyze or comprehend God or any claim to theistic (related to God) intervention. I subscribe to the notion championed by the late Harvard paleontologist, Stephen Jay Gould, who argued that science and religion work within two different areas of expertise that he labelled “non-overlapping magisterial”. However, sometimes it is difficult for society to agree on where the boundaries of these areas are and whether one discipline is intruding into another. One such problematic situation is faith healing. Faith healing is the notion that people with a disease or injuries can be healed by appealing to a deity. While it is possible that incorporating the patient’s religious beliefs into the process of the medical treatment may lead to a better outcome, the most extreme forms of faith healing claim that the medical component is not necessary for a cure. This modality of faith healing normally involves a person such as a televangelist who carries out the alleged healing act, or groups of people such as parents of a diseased child that pray for healing to occur. From a mechanistic point of view, whether faith healing works should be easy to determine. You just compare the claims to the results. However, faith healers are unwilling to have their claims openly investigated. The few people who have investigated the claims of faith healers have found that the claims for spectacular cures were either false, exaggerated, based on faulty diagnoses, or involved diseases prone to be affected strongly by the patient’s psychology. However, if the healing does not work, it can always be asserted that the faith of the person being healed, or that of the healer’s, was not strong enough, that God will refuse to be tested, that the failure of the healing was part of the divine plan, or any other ad hoc explanation with a religious component. This is why science, in principle, cannot test these claims: it cannot be stated a priori in a manner in which everyone agrees what will constitute success or failure of the claim when put to test. This ambiguity contributes to shielding faith healing from scrutiny, and if you couple this to the fact that politicians, especially those representing conservative districts, are loath to deal with this issue, you can see why the faith healing universe is a breeding ground for liars and cheats. Consider televangelist Peter Popoff. He rose to prominence in the 1980s as a faith healer. People would flock to his sermons and he would reveal to them specific information about where they lived and what illnesses they had despite never having talked with them before. He claimed that he received this information from God, and he also claimed to be able to “heal” people of their ailments. In 1986 the magician and debunker extraordinaire, James Randi, figured out that Popoff’s wife, not God, relayed this information to Popoff by electronic transmission to an earpiece he was wearing. The way this worked was that his wife would gather the information from the crowd assembled outside, and during the sermons she would tell Popoff the names, addresses, and ailments of people that then he would proceed to call out and “heal”. After being exposed as a fraud, Popoff was forced to declare bankruptcy. You would have imagined that his career as a faith healer would be over, but not so. He has made a comeback, and he is once again raking millions of dollars from people that believe in him as shown in the video below. Popoff was perhaps the easiest faith healing scammer to expose because he made himself vulnerable by using forms of deceit that could be convincingly uncovered. Unlike Popoff, however, most faith healers are careful to employ more subtle tricks that leave a lot of wiggle room for ambiguity, and they are therefore much harder to pin down. The most disturbing aspect of faith healing involves children. After all, if adult people choose to send their money to a healer or to forsake valid medical treatment for an ailment, that is their choice. But you would think that a child is another matter. As it turns out there are many cases in the U.S. where children have died because their parents did not provide them with valid medical treatments choosing instead to subject them to religious rituals. In some states, parents whose children have died as a result of these practices have been convicted of manslaughter. However, in other states there are laws that shield parents if their children die as a result of having forgone medical treatment in favor of faith-based healing alternatives. The distressing thing about these cases is that they often involve diseases that are readily treatable by modern medicine, and the afflicted children die slow painful deaths. One of the factors muddying the waters in any discussion of the effectiveness of faith healing is that most human maladies are either self-resolving or have strong psychological components. This means that in a certain amount of cases faith healing will appear to work or at least do so temporarily, and this will reinforce its perceived effectiveness among the ranks of the believers. However, when faith healing doesn’t work (which is the case in most serious diseases), one cruel by product is that the patient or their loved ones tend to blame themselves for the failures (e.g. not having strong enough faith) thus adding another level of suffering to an already dire situation. For some people, the specter of government stepping in and thwarting religious freedom and the right of parents to decide what is best for their children trumps any possible arguments against faith healers. For others, witnessing the spectacle of thousands of people being milked of their hard-earned cash or dying as a result of not choosing medical treatment for their diseases makes them cry out for justice. I believe that we must decide as a society once and for all how to assess these practices. In my opinion, establishing scientifically whether faith healing works or not is irrelevant. The issue should be viewed from a consumer point of view. If faith healers or religious leaders advertise to their followers the notion that they should forgo medical treatment for potentially life-threatening but treatable diseases in favor of faith-based approaches, then they should be held accountable for the dependability of the product they are promoting and made responsible for the outcome. Image by Russell Lee is from the National Archives and Records Administration, and its use is unrestricted. I recently went to a production of that quintessential American musical, West Side Story. While I enjoyed the whole musical with its retelling of the classic Romeo and Juliet story in the context of the rivalry between the gangs of the Sharks and the Jets in the setting of 1950s New York, it is the finger snapping that gives this musical its distinctive character and has contributed to turning it into a cultural icon. After the show, I decided that I would read up a bit on finger snapping, and I found a few interesting things about this practice which is both ancient and universal. Let’s start with music. My earliest memory of finger snapping was the theme of one of my favorite sitcoms, The Adams Family. I also remember other musical numbers that involved finger snapping like the Monkees Theme Song (The Monkees), Under Pressure (Queen), The Longest Time (Billy Joel), and King of the Road (Roger Miller). Is my age showing? But if you want more contemporary stuff, there are songs like Side to Side (Ariana Grande) or Say Something (Justin Timberlake). You also find finger snapping as an integral part of genres of music such as Flamenco in Spain, which dates back to the Middle Ages, and as part of the musical culture of ancient Greece. But finger snapping does not have to serve as a mere adjunct to a musical piece. Finger snapping can be developed into an art of its own by talented individuals. Just witness the person in the video below and his skillful use of finger snapping. Another interesting aspect of finger snapping is that it’s not just used in music. In Rome, finger snapping was one of several ways in which an audience showed appreciation for a performer. In the U.S. in the 1960s, recitations by the Beatnik poets were celebrated by finger snapping audiences, a practice that has evolved and continued in different settings nowadays. Finger snapping is used in several social and cultural contexts to convey a variety of messages ranging from approval to insults, and its uses and meanings by different groups of people can be subtle and quite complex. In fact, you don’t even have to actually carry out the deed at all to use it in communication as the utterance “Oh, Snap!” demonstrates. There are also different ways in which you can snap your fingers. While most people in the U.S. use their middle finger and thumb to snap, you can also use other fingers like the index finger. This variant was used in the finger snapping in the original Broadway production of West Side Story to make it more distinctive. There are also other finger snapping modalities such as the African Finger Snap where you hit your index finger against your middle finger, or the Persian Finger Snap which uses two hands. If you are interested in records, you should know that the record for the most finger snaps per minute is 296, which was achieved by Satoyuki Fujimura from Japan in 2017, and the loudest finger snap ever was produced by Bob Hatch from California in 2002 and was recorded at 108 decibels. Prolonged exposure to this sound level can permanently impair your hearing! But what produces the sound heard when snapping fingers? Many people think that the sound comes from the rubbing of a finger against the thumb, but this is not true. The process of snapping involves pressing a finger such as the middle finger against the thumb. This builds a tension that, when released, propels the middle finger at speeds around 3 meters per second (about 10 feet per second) toward the base of the thumb in the palm of the hand. It is the impact of the finger against this area that produces the sound we hear when fingers are snapped. You can test this by placing foam or another form of padding on the base of your palm. This will significantly dampen the sound of the snap. The process of snapping can be seen in the slow motion video below (with no audio). Observe that the collision of the finger generates ripples in the skin of the palm that travel up the wrist! And this concludes my brief foray into finger snapping. Until next blog post “play it cool boy, real cool” (snap, snap).  In this post we are going to go over the several razors available for us to use. These razors, while commonly used by philosophers and scientists, in fact are often used by regular people, sometimes without even knowing that they are using them! However, these razors have nothing to do with the removal of bodily hair. They are called razors because they allow us to deal with the complexity of the world around us by reducing (cutting) the amount of possible explanations to various phenomena. We use them to simplify our thought processes and focus on meaningful explanations without getting lost in a bog of deceiving alternatives. We will examine several of these razors and see how they can be used to deal with the amount of bilge that is often found among claims of conspiracy theories, the pseudosciences, and the paranormal. 1) Occam’s Razor. This is the most well-known of all razors. It was developed by the English philosopher William of Ockham back in the fourteenth century. This razor posits that when faced with choosing between two competing alternatives that explain a phenomenon, we should choose the simplest one. In other words, we should not make things needlessly complicated. Many conspiracy theories such as those which claim that 9/11 was a US government-supported operation or that the US never landed on the moon run afoul of this razor. The sheer number of moving parts that would have to operate just right under a mantle of secrecy to bring about the events alleged in these conspiracies is just too complicated. The simpler explanation is that there was no conspiracy.

2) Hitchens's Razor. The late author, critic, and journalist Christopher Hitchens promulgated the dictum which states that what can be asserted without evidence, can be dismissed without evidence. The implication of this razor is that the burden of proof of a claim is with the claimant. You often hear many proponents of the occurrence of paranormal events declare that these phenomena have not been disproven. By this razor’s criteria, this argument is irrelevant. If you want people to accept a claim, YOU have to prove it is true, and you had better do a very damn good job at it to be taken seriously. 3) Sagan’s Standard. The late astronomer Carl Sagan popularized this aphorism which postulates that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. This standard recognizes that not all claims are created equal. Fantastical claims which run counter to scientific laws or mountains of evidence should only be accepted upon the production of truly remarkable evidence. By the metrics of this razor, claims for psychic phenomena, faith healers, and other such things fall short of the level of proof required to accept them. 4) Alder’s Razor. The Australian mathematician Mike Alder published an essay describing this razor, although at the time he called it “Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword” (which is a cooler name). The brutal postulate of this razor (or sword) states that what cannot be settled by experiment or observation is not worth debating. If you have ever had an exchange with a flat Earth proponent and regretted afterwards having lost one hour of your life, you have experienced in the flesh what Alder was talking about. 5) Popper’s Falsifiability Principle. The great philosopher of science Karl Popper coined this famous principle which states that for something to be considered scientific it must be falsifiable. What this means is that there must be a way of proving that a claim is false if it indeed is false, otherwise said claim is not scientific. And if a claim is not scientific, its truthfulness will never be settled by observation or experiment (see Alder’s Razor above). A classical feature of the thinking of those making fantastical claims is that they always move the goalposts. No possible observation or experimental result can prove them wrong. Therefore they can’t be right. On the other hand, science can be right because it can be wrong. 6) Hanlon’s Razor. This particular razor of uncertain origin deals with the motivations behind those who propose fantastical claims. It states that one should never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. While it is true that within the ranks of those who believe in and peddle fantastical claims there are many liars and cheats, this razor reminds us that there are also scores of honest individuals who are just guilty of self-delusion or who have been bamboozled into accepting and defending these claims. In a recent post I reminded my readers about the dangers of keeping one’s mind too open (i.e. it can easily be filled with trash). Well, I guarantee that if you put these razors between you and the vast vortices of irrationality and trickery that swirl about us, your mind will be spared! The image is by Horst.Burkhardt is used here under an Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed