|

Some people argue that science is too conservative and set in its ways. They claim that science favors a herd mentality where scientists are rewarded for following the mainline theories and are penalized for dissent against the establishment. It is argued that this creates a hostile environment for radical new ideas that hinders scientific progress and slows down innovation. Is this true? Let’s look at 3 of these ideas that were rejected by science but turned out to be true.  Carlos Finlay Carlos Finlay Mosquitoes transmit Yellow Fever At the end of the 19th century, diseases were considered to be transmitted through person to person contact, but the mechanisms of the transmission of diseases like Yellow Fever eluded scientists. The Cuban physician, Carlos Finlay, developed a theory that Yellow Fever was transmitted by mosquitoes, and he performed studies where he had a partial success in having some volunteers bitten by mosquitoes develop mild cases of Yellow Fever. Finlay presented this idea to the scientific community in Cuba in 1881 and later in the United States. However, Finlay’s evidence turned out to be problematic, generating many unanswered questions, and his presentation was less than stellar. His idea was met with derision and he was called a crank. For nearly 20 years he persevered in his research, which he funded himself, and continued generating stronger evidence and publishing it. During this time, the Scottish physician, Patrick Manson proposed (based on his earlier work on the transmission of a disease-causing worm by mosquitoes) in 1894 that the malaria parasite could be also be spread by these insects. A few years later the British medical doctor, Ronald Ross, proved that this was indeed the case. Towards the end of the century, Finlay’s idea started looking less farfetched and gained enough notoriety to warrant it be put to test. In 1900 Walter Reed carried out his famous experiments in Cuba that demonstrated that mosquitoes transmit Yellow Fever, and Finley was vindicated.  Alfred Wegener Alfred Wegener Continents Move In 1912 the German geophysicist and meteorologist, Alfred Wegener, proposed the idea that the continents of the Earth are moving away from each other, and that they were once joined together into a great landmass he called Pangea. His evidence consisted of how the shape of the continents could be made to fit together like pieces of a puzzle, the distribution of both current and fossil species across continents, and how the geological strata in one continent matched those of others. Unfortunately, not only did Wegener lack a credible mechanism to explain this proposed continental movement, but he made several mistakes including overestimating the rates of movement. His idea of continental drift was panned by the scientific establishment and labelled a “fantasy” and “pseudoscience”, and he was publicly ridiculed. Through all this, Wegener persevered, refining his ideas and correcting his mistakes. However, it was only in the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of the new science of paleomagnetism, that numerous studies demonstrated that the seafloor indeed was spreading and that the continents were moving. Sadly, Wegener died during an expedition to Greenland in 1930 and did not live to see his idea incorporated into the modern theory of plate tectonics. Today the movement of continents can be measured with satellites.  Stanley Prusiner Stanley Prusiner An infectious Agent with no DNA or RNA There are diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or kuru that back in the 1970s were thought to be caused by viruses that act very slowly. The American neurologist and biochemist, Stanley Prusiner, became interested in these slow virus diseases and managed to isolate pure preparations of the infectious agent. Prusiner found that these preparations contained protein but were devoid of nucleic acids (nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA carry the genetic information in all living things including viruses), and that agents that destroyed proteins but not nucleic acids eliminated the infectivity of the preparations. Therefore Prusiner concluded, based only on this evidence, that the infectious agent was a new infectious entity made up solely of protein. He proceeded to publish an article where he not only claimed to have discovered a new infectious agent unlike any found before, but he also christened this agent, prion, a name put together from the words “proteinaceous” and “infective “ (although “proteinaceous” and “infective” should yield “proin”, “prion” sounded better). The vast majority of scientists did not accept his idea, which at the time went against everything that was known about the nature of infectious agents, and a good number of them heaped vitriol upon Prusiner. The fact that Prusiner was a stellar networker and salesman of his ideas and managed to get multimillion dollar grants did not soften their attitude. Although Prusiner kept researching and making new discoveries about prions, experiments in this field used to take years, so scientists were slow to try to reproduce his experiments. Eventually others were able to replicate his results and the concept of prions was accepted. Prusiner won the Nobel Prize in 1997. Now let's go back to our question. Does science create a hostile environment for radical new ideas that hinders scientific progress and slows down innovation? Two things have to be understood about radical new ideas in science: 1) the majority of radical new ideas turn out to be wrong, and 2) there is usually not one or two of these radical new ideas but dozens of them. Which ones are correct and which ones aren't? Should the limited funds allocated for science be made available to everyone who has a radical new idea? The answer is, of course, No. Decisions have to be made as to which ideas are more plausible than others. Science tends to give preeminence to that which is established. If you want to upend established science, the burden of proof is on you. The truth is that the radical news ideas of Finlay, Wegener, and Prusiner were not backed by convincing evidence. Their evidence generated more questions than answers, and scientists were not moved to throw orthodoxy out the window, at least right away. The insults and humiliations that Finley, Wegener, and Prusiner endured are certainly regrettable and objectionable, but this has to do more with human nature than with science. However, as more and better evidence was generated, questions were answered, errors were corrected, and experimental results were replicated, their ideas were accepted. They were right, and the establishment was wrong. But let’s be clear on something, the initial rejection of their ideas was totally warranted, even if they did turn out to be true. The photos of Carlos Finlay and Stanley Prusiner, and the photo of Alfred Wegener from the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg are all in the public domain.

8 Comments

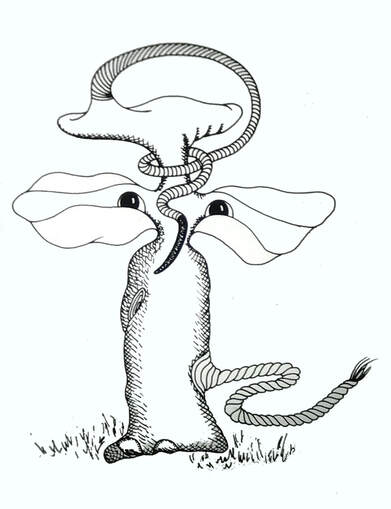

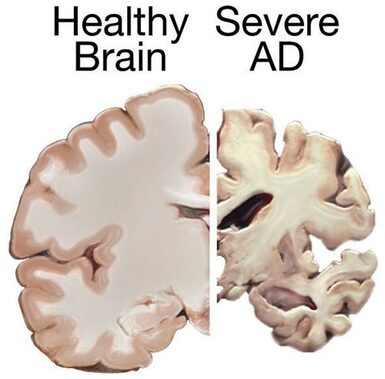

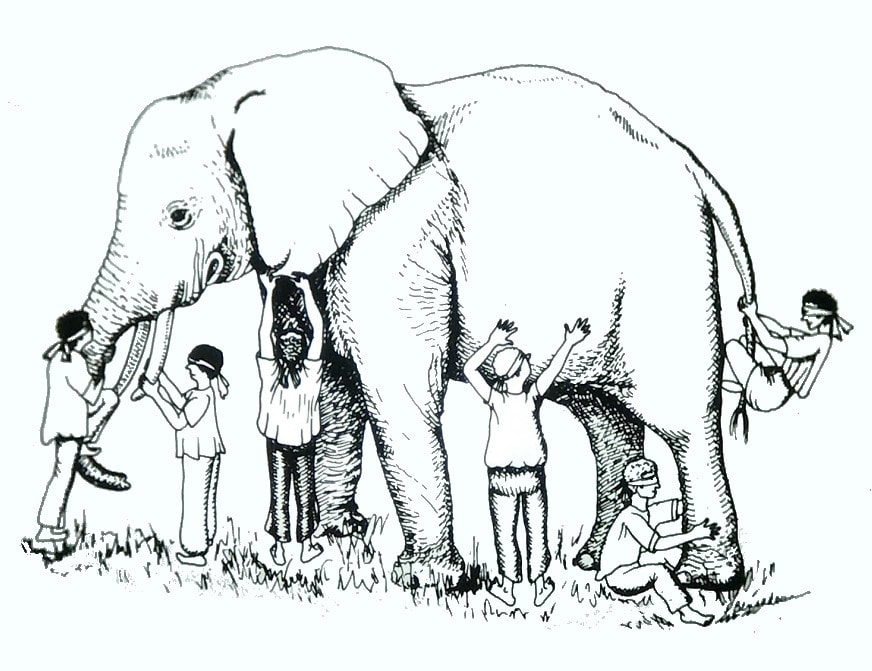

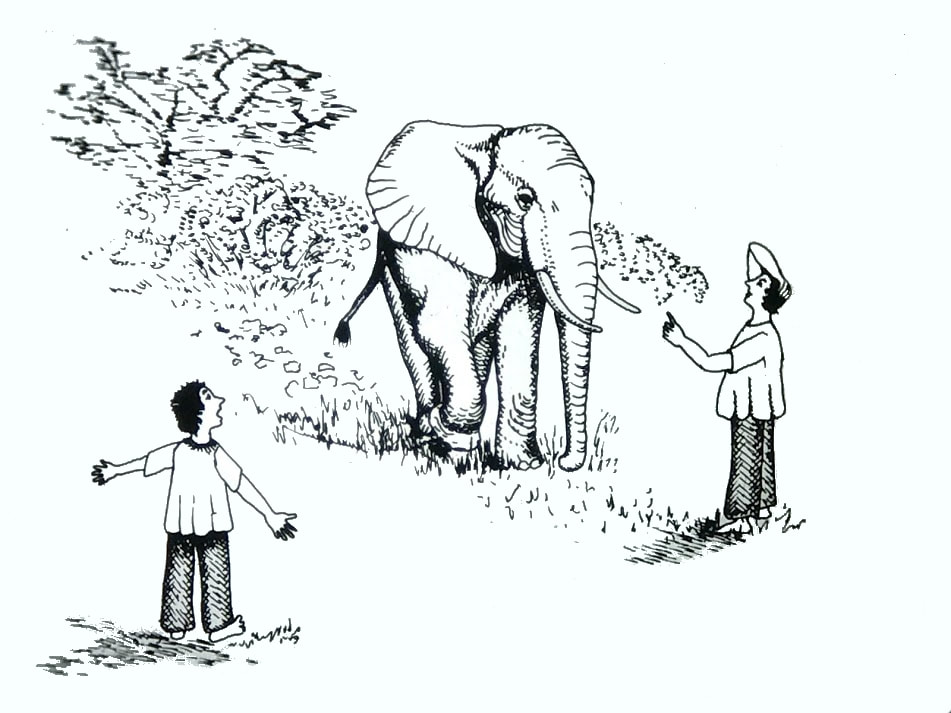

I have tried to explain in my blog how scientific theories arise, and how the initial theories generated in an emerging scientific field are very different from the fully developed theories of a mature scientific field. In this post I will attempt to do this again using the ancient parable of the blind men and the elephant. This is a story found in Hindu and Buddhist texts dating back more than 3,000 years. It has been used in religious and philosophical contexts to illustrate how we often think we know the truth, even though we have just grasped only part of it. The most famous version in English is the poem entitled “The Blind Men and the Elephant” written by the poet John Godfrey Saxe. So let’s imagine a physical reality which in our case has the shape of an elephant, and that we will call “the elephant”. Let’s also imagine an emerging scientific field that is trying to research said elephant. The field is represented by six scientists who seek to figure out how the elephant looks. But the scientists are in the dark as shown by the blindfolds they are wearing. So each of these scientists approaches the elephant and begins to research it. In our story this is exemplified by the scientists touching the elephant. Scientist 1 grabs the elephant by the tail and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a rope. Scientist 2 touches the elephant’s leg and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a tree. Scientist 3 touches the side of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a wall. Scientist 4 touches the ears of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a fan. Scientist 5 grabs the tusk of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a spear. Scientist 6 feels the moving trunk of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a snake. In the various versions of the parable, the blind men quarrel with each other, as each is one is convinced that their version of what the elephant looks like is the truth. The parable ends mocking their hubris at thinking that each one knows the truth when really none of them knows the whole truth (the real shape of the elephant). However, there is one fundamental difference between these versions of the parable and mine. In my version, the blind men are scientists, and that makes all the difference! These scientists are not working in isolation. They discuss and cooperate with each other. Mind you, some of these scientists may argue very forcefully in favor of their particular idea of how the elephant looks, and others may argue back just as forcefully that they are wrong. However, these scientists go to meetings, give presentations, face each other, exchange information, and publish their research results regarding the shape of the elephant in peer-reviewed journals. Each scientist tries to reproduce the observations made by others. The scientist who touched the tail and concluded that the elephant was like a rope, also touches the leg of the elephant, and realizes that he should modify his original hypothesis to incorporate this new information. Thus he proposes that the elephant looks like a tree with a rope sticking out of it. The scientist who touched the side of the elephant and concluded that the elephant was like a wall, also touches the ear, and realizes he should modify his original hypothesis to include this information. He now proposes that the elephant looks like a wall with a fan sticking out of it. The same happens with the other scientists. As new information becomes available, scientists modify their original views and try to harmonize all the knowledge about the elephant. Mind you, this can be a messy process that may be hampered by methodological difficulties. For example, some scientists may not reach high enough to touch the ear, or may not be nimble enough to catch the tail and they remain unconvinced of claims that the elephant is like a fan or a rope. Nevertheless, after a period of time, a majority of these scientists come to an agreement and put out the first theory regarding how the elephant looks!  The First Theory The First Theory As you can see from the image, this theory about how the elephant looks is a very preliminary one. However, there is something “elephant-like” about it. Clearly the theory has grasped some aspects of the reality the scientists were studying. In its present form the theory may even have some usefulness, but the theory is clearly incomplete. It does not reflect the full reality of how the elephant looks. Nevertheless, this theory represents a group effort. The scientists are trying to fit all the relevant information that is available to come up with the answers. So the research continues. A scientist may find that the elephant has not one leg but four. The scientist reasons, “Hmm, the elephant is like four trees? That doesn’t make sense.” Another may find that the surface of the wall is much larger and is connected to the four legs at the bottom and completely surrounds the elephant at the middle. He may think, “What type of wall is this? The elephant may not be like a wall after all.” As more observations keep piling in, the original theory is found to be unsatisfactory and is replaced by one that incorporates the new observations. This new theory is more complete and its image would look more like an elephant. Scientists develop new methods to investigate the shape of the elephant generating more information. Scientists from other disciplines may also take up the research of how the elephant looks bringing in their expertise and new ideas. As this process keeps going and the scientific field that studies the elephant reaches maturity, a theory is put forward that explains the majority of the observations regarding how the elephant looks. The theory is used to make predictions that turn out to be true and generates practical applications. The scientists stop arguing with each other regarding the most relevant aspects of what the elephant looks like, and they reach a consensus. Thus something has happened that has never happened in any of the previous versions of the parable. The scientists studying the elephant don’t have their blindfolds on anymore. They are able to behold the true shape of the elephant. By working together, exchanging information, trying to reproduce what others did, and trying to come up with explanations for all the observations, they have discovered the truth! That is how science works. The images by Paula Bensadoun can only be used by permission from the author.  In this blog I have pointed out that there is a progression in emerging fields of scientific inquiry where competing theories are evaluated, those that do not fit the evidence fall out of favor, and scientists coalesce around a unifying theory that better explains the phenomena they are studying. However, even as a new theory that better fits the available data is accepted in the field, there are individuals who contest the newfound wisdom. Instead of accepting the prevailing thinking, these individuals buck the trend, think outside the box, and propose new ways of interpreting the data. I have referred generically to individuals belonging to this group of scientists that “swim against the current” as “The Unreasonable Men”, after George Bernard Shaw’s famous quote, and I have stated that science must be defended from them. The reason is that science is a very conservative enterprise that gives preeminence to what is established. Science can’t move forward efficiently if time and resources are constantly diluted pursuing a multiplicity of seemingly farfetched ideas. However, this is not to say that the unreasonable man should not be heard. There are exceptional individuals out there who have revolutionary ideas that can greatly benefit science, but there is a time for them to be heard. One such time is when the current theory fails to live up to expectations. I am writing this post because such a time may have come to the field of science that studies Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating dementia that currently afflicts 6 million Americans. The disease mostly afflicts older people, but as life expectancy keeps increasing, the number of people afflicted with AD is projected to rise to 14 million by 2050. The disease is characterized by the accumulation of certain structures in the brain. Chief among these structures are the amyloid plaques, which are made up of a protein called “beta-amyloid”. The current theory of AD pathology holds that it is primarily the accumulation of these plaques, or more specifically their precursors, which is responsible for the pathology. Therefore, it follows that a decrease in the number of plaques should be able to alleviate or slow down the disease. This has been the paradigm that pharmaceutical companies have pursued for the past few decades in their quest to treat AD. Unfortunately, this approach hasn’t worked. For the past 15 years or so, every single therapy aimed at reducing the amount of beta-amyloid in the brain has led to largely negative results. In fact, some patients whose brains had been cleared of the amyloid deposits nevertheless went on to die from the disease. Several arguments have been put forward to explain these failures. One of them is the heterogeneity in the patient population. Individuals that have AD often have other ailments that may mask positive effects of a drug. According to this argument, performing a trial with patients that have been carefully selected stands a greater chance of yielding positive results. Another argument is the notion that many past drug failures have occurred because the patient population on which they were tested was made up of individuals with advanced disease. According to this argument, drugs will work better with early-stage AD patients that have not yet accumulated a lot of damage to their brains. Even though many researchers still have hopes that modifications to clinical trials like those suggested above will have the desired effect as predicted by the amyloid theory, an increasing number of investigators are considering the possibility that this theory is more incomplete that they had anticipated and are willing to listen to new ideas and open their minds to the unreasonable man.  One example of these men is Robert Moir. For several years he has been promoting a very interesting but unorthodox theory of AD and getting a lot of flak for it. He dubs his hypothesis “The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease”. According to Dr. Moir, the infection of the brain by a pathogen or other pathological events triggers a dysregulated, prolonged, and sustained inflammatory response that is the main damage-causing mechanism in AD. In this hypothesis, the production and accumulation of the amyloid protein by the brain is actually a defense mechanism! Dr. Moir agrees that sustained activation of the defense response will lead to excessive accumulation of the amyloid protein and that this eventually will also have detrimental effects. However, even though reduction in amyloid protein levels may be beneficial, accumulation of the amyloid protein is but one of several pathological mechanisms. Moir stresses that the main pathological mechanism that has to be addressed by AD therapies is a sustained immune response, which over time causes brain inflammation and damage. He considers that accumulation of the amyloid protein is a downstream event, and it is known that the brain of people with AD exhibits signs of damage years before any amyloid accumulation can be detected. But much in the same way that Dr. Moir has been promoting his unconventional theory, there are many other theories proposed by others. Oxidative stress, bioenergetic defects, cerebrovascular dysfunction, insulin resistance, non-pathogen mediated inflammation, toxic substances, and even poor nutrition have been proposed as causative factors of AD. This is the big challenge that scientists face when opening their minds to the arguments of the unreasonable man: there is normally not one but many of them! So who is right? Which is the correct theory? And why should just one theory be right? Maybe there is a combination of factors that in different dosages produce not one disease but a mosaic of different flavors of the disease. And maybe the amyloid theory is not totally wrong, but just merely incomplete, and it needs to be expanded and refocused. Or maybe the beta-amyloid theory is indeed right and all that is required for success is to tweak the trial design and the patient population. Maybe, maybe, maybe… When a scientific field is beginning, or when it looks like a major theory in a given field is in need of reevaluation, there always is confusion and uncertainty. Scientists in the end will pick the explanation(s) that better fits the data and take it from there. They did that when most scientists accepted the amyloid theory and they will do it again if this theory is found wanting. The new theory that replaces the amyloid theory will not only have to explain what said theory explained, but it will also have to explain why the old theory failed and what new approach must be followed to successfully treat the disease. In the meantime, Dr. Moir’s theory, along with a few others, is the center of focus of new research evaluating alternative theories to explain what causes AD. The amyloid theory or aspects of it may still be salvageable, but in the field of AD it certainly looks like the time for the unreasonable man has come. Note: after I posted this, I became aware of an article published in the journal Science Advances that proposes a link between Alzheimer's Disease and gingivitis (an inflammation of the gums). The unreasonable men are restless out there! The image is a screen capture from a presentation by Robert Moir on the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund YouTube channel, and is used here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use.The brain image from the NIH MedlinePlus publication is in the public domain.  The scientific consensus has been getting a bad rap lately. Some people argue that whether science is right or not about an issue is not decided by majority vote. Rather, it is claimed, it only takes one scientist to be right to decide whether the science regarding an issue is true or not. Those that make this argument then go on to provide a list of scientists that went against the consensus and prevailed. The people making these argument then proudly proclaim that in science there is no such thing as consensus, that science does not require a consensus, and if there is a consensus, then it isn’t science! Let’s try to understand a few things about the scientific consensus.

A scientific consensus is not reached when scientists get together and “vote”. A scientific consensus, unlike the use of this word in other fields such as politics, does not involve a compromise. Also the word consensus is sometimes used to denote the current state of a field as in “the current consensus”. In a new field of study the term “scientific consensus” really means “the current opinion” and it is understood that such opinion is very likely to be overturned in the future. This is not the meaning of consensus that better serves science in the public sphere when dealing with topics like climate change or evolution. The meaning of scientific consensus that we should seek is that consensus attained in a field of science that is backed by a fully developed scientific theory. A field of science that has not generated a fully developed scientific theory is incapable of generating a true scientific consensus. The reason this is the case is because a fully developed scientific theory has grasped important aspects of reality in its formulation and is likely to have a high degree of completeness. How is such a theory developed? When a field of study is in its early stages, scientists from several countries, ethnic backgrounds, beliefs, political persuasions, etc. begin tackling a problem. All these scientists bring their intellect and life experience to bear on answering the questions being investigated. Initially there is a multiplicity of possible answers, there are uncertainties, deficiencies and limitations in the methodologies, and there is confusion. Many scientists go down blind alleys only to find they have wasted their time on a wrong approach and have to turn back. Some explanations emerge that seem to be better than others. Methodologies are improved. Hypotheses are refined. Exceptions are explained. Scientists from other areas enter the field and bring new tools and ideas (a very important development). The research performed in these other fields is found to be complementary to the research in the emerging field. Eventually as the field matures scientists from different laboratories using different methodologies begin obtaining the same results and elaborate models that they use to make predictions (another very important development). Some predictions are not fulfilled and the models that generated them fall by the wayside and are replaced by new models that are more accurate at explaining the data and making new predictions. Eventually the field coalesces around a theory. The theory is used to generate practical applications and to explain observations in other areas of science. A theory developed through the process described above is not an ephemeral construct that can be overturned at any time. The very technology that we use in our everyday lives depends on hundreds of solid scientific theories that have never been disproven. Many people who do not understand the nature of scientific truth confuse the overturning of a scientific theory with its refinement. This is because there is the erroneous notion that scientific theories should explain everything, and this is not the case. A scientific theory only has to answer the most important questions raised by scientists. Thus, when a fully developed scientific theory is produced in a field of study this means that scientists have stopped arguing with each other about the salient points addressed by the theory. In other words, they have reached a consensus. This is the true meaning of a scientific consensus. Of course, the fact that there is a consensus doesn’t mean that everything has been settled. Scientists that agree with evolution are still debating how evolution happens. Scientists that agree with climate change are still debating its extent and mechanisms. Nevertheless, a consensus does mean that the major overreaching question in the field has been answered to the satisfaction of the vast majority of the scientists involved in the research. The consensus can, in principle, be modified if the underlying theory that backs the consensus is found to be incomplete, but this is only true if the refinements to the theory in the form of new observations, new data, or new interpretations of old data or old observations, significantly modify those parts of the theory that are vital for the consensus. In the case of a fully developed scientific theory this is no easy task, and the burden of proof is on those who seek to modify the theory. Some people claim that this promotes a herd mentality that leads to dissenting scientists being penalized and those that are compliant being rewarded resulting in the discouragement of innovation. However, what has to be understood is that science is a very conservative enterprise that sets a very high bar for those seeking to challenge what is considered established knowledge. If you are going against the prevailing theory, you’d better have very good evidence. This is not the product of a herd mentality or a way to discourage innovation: it is a way of protecting established science against error. In the public debate, when you hear that a consensus has been reached in a particular field of science, you need to ask about the nature of the underlying theory that backs it. If the theory fulfils the requirements of a fully developed scientific theory, then the consensus is good. A consensus is only as good as the theory that supports it. However, suggesting that there is no such thing as a scientific consensus or that it is irrelevant is nothing more than a strategy to delegitimize science. It has been used in the past by entities such as the cigarette lobby, and it is being used today by creationists, climate change deniers, and other groups that seek to further their anti-science agendas. Image by Nick Youngson used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license. Some scientific theories that are in the way of religious, political, and corporate interests have been getting a bad rap. These theories are claimed to be false by their foes. So for example, creationist claim that evolution is false, climate change deniers claim that global warming is false, and so on. In fact, many people seem to imply that theories are ephemeral, and to buttress their claim they offer a list of theories that have been proven “false”. Why should we rely on a scientific theory to affect public policy today if it can be shown to be false tomorrow? In addressing this issue there are several things we have to consider. Before we begin, we need to make the clarification that the word “theory” in the popular parlance can be a synonym for a guess or a very preliminary explanation. In science, a theory is a vastly more stable form of knowledge. In fact, if the theory is sufficiently developed, it in itself can become a fact. So what are the characteristics of a sufficiently developed theory? They are: 1) It explains the existing observations and experimental results. 2) It has generated predictions that have been found to be true. 3) It has generated practical applications that work. 4) Results from other scientific disciplines corroborate the theory and the theory corroborates results in other scientific disciplines. Please read the list above again carefully. Don’t you think that when a theory fulfils these characteristics we can say with confidence that it has clearly grasped important aspects of the realities it’s trying to explain? But, you may ask, what if a genius like an Einstein comes along and thinks up a new interpretation for everything the theory explains and predicts, and expands it into a different theory to explain new things? Can’t we say then the theory was proven false?  Well, let’s consider what Einstein did. He reinterpreted Newton’s laws of gravitation and motion, and came up with explanations for phenomena the Newtonian interpretations could not explain. Einstein thus relegated Newton’s laws to particular cases where velocities are much lower than that of the speed of light or when very strong gravitational fields are not involved. But here is the thing: the speeds at which planets, rockets, space probes, and objects in everyday life move, and their behavior in the gravitational fields that they encounter most of the time, can be described with a satisfactory level of accuracy by Newton’s laws. The existence of a planet (Neptune) and the return of a comet (Halley’s Comet) were predicted using Newton’s laws. The life of astronauts and the integrity of multimillion dollar space probes depend on the veracity of the calculations employing Newton’s Laws. Is it fair to say that Einstein proved Newton’s theories were false? Of course not! Einstein showed Newton’s theories were incomplete, and this is what the public has to understand when discussing scientific theories. Sufficiently developed scientific theories cannot be false, they can only be incomplete. When assessing scientific theories, it is counterproductive to talk in terms of true or false. What has to be discussed is whether a theory has been formulated at a high enough level of detail, in other words, whether the theory is complete enough. We don’t need theories to be 100% true. They can’t be (nothing can), and they don’t have to be. We only need the theory to be complete enough to be useful for society. Finally, it must be pointed out that the vast majority of scientific theories are not “big name” theories such as the theory of evolution or global warming. There are hundreds of scientific fields and subfields that have given rise to thousands of theories most of which are boring, highly technical, and devoid of importance to the “culture wars”. Therefore they do not make the news, and non-scientists are not even aware of them. Most of these theories have never been overturned, and in fact form the basis of modern science leading to tens of thousands of practical applications and policies. If these theories were not sufficiently complete representations of reality, modern life would not be possible! So next time you are pondering the worthiness of a scientific theory, remember, it's all in the completeness. The figure is a collage of a copy of a painting of Isaac Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1689), which is in the public domain, and a photograph of Albert Einstein by Orren Jack Turner obtained from the Library of Congress, which is also in the public domain because it was published in the United States between 1923 and 1963 and the copyright was not renewed. 2/7/2018 Is the Earth round? Avoiding The Absolute Truth to Find the Practical Truth: the Devil is in the Level of DetailRead NowMost people hold a “binary” notion of the truth. For them things can either be true or false, because that which is false cannot be true, and that which is true cannot be false. We will call this notion the “absolute truth”. I want to argue that this absolute truth notion is unsatisfactory and impractical at addressing the worthiness of scientific theories. For this purpose I will use an example. Consider the idea that the Earth is flat. For people in antiquity living in a flat place like the plains or a desert it probably made sense to think this, but eventually the ancients figured out that the Earth was not flat. The Earth is round and we know that for a fact nowadays. So, the Earth is flat: false, the Earth is round: true; right? Actually, the Earth is not round! As Isaac Newton proposed and was later found to be correct, the Earth, due to its rotation, is an “oblate spheroid”, which means it is flater at the poles and bulging at the equator (the distance from the Earth’s center to sea level is 13 miles longer at the equator). OK, so, the Earth is round: false, the Earth is an oblate spheroid: true, right? Well, not quite. The Earth is an oblate spheroid, but the southern hemisphere is wider than the northern hemisphere giving the Earth a bit of a pear shape. Fine, so the Earth is an oblate spheroid: false, the Earth is a pear-shaped, oblate spheroid: true, right? Actually, even this is false! The Earth’s mass is not distributed evenly across the planet, and the greater the mass, the greater the gravitational force, which leads to the creations of bumps in the Earth’s crust. Additionally these bumps change overtime due to the movement of continental plates, the changing weight of the oceans, lakes, ice masses, and atmosphere, and the gravitational pull of the sun and the moon. All of these processes can deform the Earth’s crust by the order of millimeters to a few dozen centimeters daily and by much larger amounts over geologic times. So the Earth is a bumpy, shapeshifting, pear-shaped, oblate spheroid? Yes. Wahoo, we did it! At last we have the absolute truth! The Earth is an pear-shaped, oblate spheroid: false, the Earth is a bumpy, shapeshifting, pear-shaped, oblate spheroid: true, right? At this point you are probably thinking: seriously, are you kidding?  This is the problem with the absolute truth notion: it ignores the level of detail that is required for adequately describing physical phenomena. The level of detail that is required from a description of the shape of the Earth will vary depending on what you are intending to use it for. For surveyors determining distances in small patches of the Earth’s surface, a flat Earth model is perfectly suitable, as the error in the measurements is negligible. For people dealing with time zones, the round Earth description is perfectly adequate. On the other hand, satellite orbits can be affected by small deviations of the Earth’s crust from a perfect sphere, so people following satellites must take into account the oblate spheroid and pear deformities of the Earth. Similarly, people running particle accelerators must understand that the Earth is constantly shifting its shape so they can keep track of very small deformities in the Earth’s crust that arise daily and may mess up their measurements. The vast majority of people would accept that the claim that the Earth is flat is false (low level of detail). On the other hand, most people would consider further refinements to the round Earth claim such as the oblate spheroid; pear-shaped, oblate spheroid; or bumpy, shapeshifting, per-shaped, oblate spheroid to be a needless amount of precision (too high a level of detail), and rightly so. The type of deviations from a spherical shape that these highly detailed models of the Earth deal with is at most about a dozen miles. If you take into account that the Earth’s radius is 3,959 miles, we are talking about a difference of 0.3%. By this token the Earth’s crust, despite its mountains and sea trenches, is very smooth. So for the use that most of us make of the information regarding the shape of the Earth, a round Earth model is an acceptable level of detail. Depending on what you are trying to explain or achieve, trying to find the absolute truth may be not only impossible or unnecessary, but also cumbersome. So we come to the paradoxical realization that seeking the absolute truth may actually hinder or prevent our discovery of the practical truth! When scientists seek the truth regarding physical phenomena, what they have in mind is the practical truth which is a truth defined at a sufficiently high level of detail to explain the phenomena they are studying and derive predictions and useful applications. Later on other scientists may seek to explain things at a higher level of detail to address more complex questions that a lower detailed truth can’t answer satisfactorily, and so on. What the public has to understand is that a scientific theory does not have to explain everything to be considered “true”. It just has to explain the relevant phenomena at a sufficiently high level of detail to generate accurate predictions and useful applications. The debate should not be about whether a given theory is true or false, but rather about whether a theory has been formulated at a sufficiently high level of detail for society to benefit from it. The image from NASA is in the public domain. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed