|

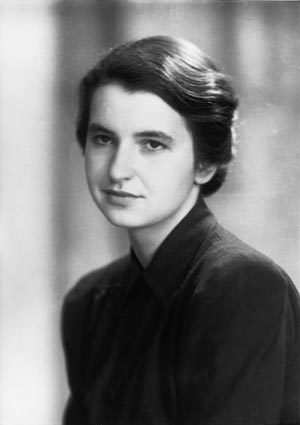

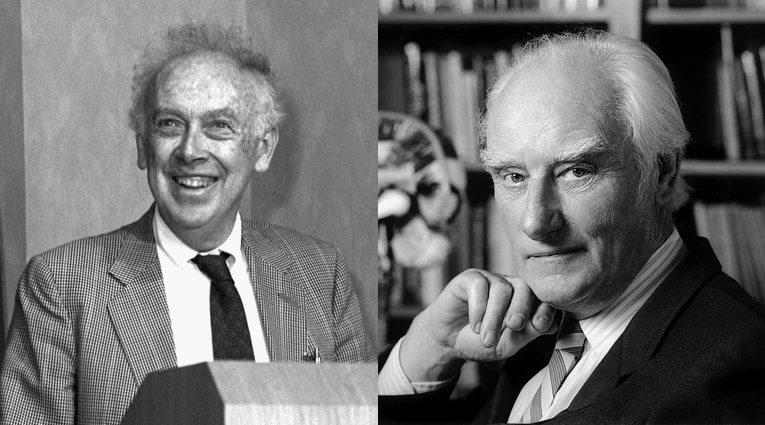

Every activity performed by groups of human beings interacting with each other tends to have some drama, and science is no exception. The quest of scientists to discover, be recognized and respected, and remain relevant has produced amazing stories that form a permanent part of the lore of scientific research. And these stories have it all: triumph and tragedy, the clash of strong willed characters, and the fireworks displays stemming from the mixing of the most honorable and dishonorable aspects of human nature. But these stories seldom make it to the end product of scientific research in which scientists report the results of their work: the scientific article. Scientific articles tend to be highly technical, full of jargon, and are mostly read by specialists. However, many scientific articles have subtle and not so subtle hints of what’s going on behind the science. Today we will take a look at two scientific articles related to two such stories. The first one is the famous article entitled, A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid, published in the Journal Nature in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick. In this article, these two scientists propose a structure for the chemical molecule that contains the blueprint of life: DNA. This article ushered a revolution that changed science and the word forever. The most mentioned passage in this article is the one below: It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material. This whopper of a sentence, which has been described as anything from “coy” to “one of the greatest understatements in the history of science”, makes a reference to the fact that the model of the structure of DNA that Watson and Crick proposed explained a phenomenon which at the time was the holy grail of the biological sciences (how genetic information is copied). However, the passage that reveals some of the human drama behind the science is found in the previous paragraph. The previously published X-ray data on deoxyribose nucleic acid are insufficient for a rigorous test of our structure. So far as we can tell, it is roughly compatible with the experimental data, but it must be regarded as unproved until it has been checked against more exact results. Some of these are given in the following communications. We were not aware of the details of the results presented there when we devised our structure, which rests mainly though not entirely on published experimental data and stereochemical arguments.  Rosalyn Franklin Rosalyn Franklin Watson and Crick never worked with DNA themselves. As they wrote, they relied on work already published by others and on their own theorizing. However, they claim their model agrees with “more exact results” in the following communications. This makes an allusion to two additional articles published simultaneously with theirs by other researchers. Among them was Rosalyn Franklin. Watson and Crick claim they were not aware of the “details” of these results when they put their model together, but this carefully worded statement is misleading. Franklin’s work with DNA was made available to Watson and Crick without her knowledge, and whether detailed or not, it was a crucial part of the puzzle that allowed them to solve the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick would go on to be corecipients of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1962. Rosalyn Franklin continued her work and went on to make several important discoveries, but died from Cancer in 1958 at the age of 38 never having known that it was her uncredited work that allowed Watson and Crick to figure out the structure of the molecule of life. The second article we will consider today is famous because of its infamy. It is entitled: Warburg Effect Revisited: Merger of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and was published in the journal Science in 1981 by Efraim Racker and Mark Spector.  Efrain Racker (left) and Mark Spector (right) Efrain Racker (left) and Mark Spector (right) In the late 1970s, Efraim Racker was one of the surviving elder scientists of biochemistry. He had won numerous awards for his work but not the Nobel Prize. When the 1978 Nobel Prize was awarded to Peter Mitchel for his theory regarding how cells obtain their energy, there was consternation in the scientific world as it had been Racker who had performed the experiments that had conclusively demonstrated Mitchel’s theory to be true. Undeterred by this, at the beginning of the 1980s, Racker took up researching an unexplained phenomenon that he had addressed off and on throughout his career called the Warburg Effect. Normal cells use oxygen as part of the normal mechanism of producing the energy they need. However, when cells become cancerous, they switch their energy producing mechanisms, in large part, to one that does not require oxygen even if oxygen is present. Many scientists think that this switch holds the key to explain what causes cancer and how it can be treated. At the same time a bright Ph.D. student named Mark Spector joined Racker’s lab and began researching the Warburg Effect. Spector proved to be a talented researcher making discoveries in a few months that would take others years. By 1981 he had put together a wonderful story linking cancer-causing genes to signaling pathways that led to changes in the bioenergetics of the cells which explained the Warburg Effect. This result was really big, and probably Nobel Prize material. The Warburg effect’s relation to cancer had not been explained for decades. Racker was elated. The passage in the article that best describes the sense of fulfilment, optimism, and aspirations that Racker had is the first sentence which is not even a scientific statement but a quote from the English writer Gilbert K. Chesterton. There are no rules of architecture for a castle in the clouds. And herein lies the brutal irony of this story. Spector tuned out to be a con-man. He had falsified the data! Racker retracted the article and dismissed Spector from his lab. Racker would still perform important research for the next decade, but the Nobel Prize would elude him. He died from a stroke in 1991. The Warburg Effect remains unexplained, and is still an active area of investigation in cancer. These are but two of the thousands of stories lurking behind the technical jargon, the graphs, and the tables in the pages of the scientific literature. Photos of Rosalind Franklin by Silver Screen and of James Watson by the National Cancer Institute are in the public domain. Photo of Francis Crick by Marc Lieberman used here under an Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5) license. I do not own the copyright to the articles mentioned here from which the text is quoted or the image of Efrain Racker and Mark Spector from the journal Science (Vol. 214, No. 4518 (Oct. 16, 1981), pp. 316-318), Copyright Cornell University. These are used here under the doctrine of Fair Use.

0 Comments

In his excellent 1994 book, The Astonishing Hypothesis, the late Nobel Prize winning scientist, Francis Crick (co-discovered of the structure of DNA with James Watson), put forward a hypothesis that boggles the mind. He wrote: “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” He claimed that this hypothesis is astonishing because it is alien to the ideas of most people. This is presumably because, when it comes to our mind, we believe that there is something special about it. Clearly the mind is more than the product of the activity of billions of cells, no? Exalted emotions such as love and compassion and empathy or belief in the divinity or free will cannot just be a byproduct of chemical reactions and electrical impulses, right? But why would that be the case? Consider an organ like the intestine. It’s made up of billions of cells that cooperate to produce digestion. Most people will agree with the notion that the intestine produces digestion. So, if we can accept that the cells that make up the intestine produce digestion, why can’t we accept that the cells that make up the brain produce the mind? Let’s just touch on something simple, but that nevertheless goes to the very core of our notions of free will and consciousness. Consider an action such as performing the spontaneous motor task of moving a finger to push a button. In our minds we would expect that this and other such actions entail the following sequence of events in the order specified below: 1) We become aware (conscious) that we want to perform the action. 2) We perform the action. But what goes on in our brains even before we become aware that we want to perform the action? Many people would guess: nothing. Whatever brain activity occurs associated with the action must logically occur after we become aware that we are going to perform the action. After all, how could there possibly be nerve activity associated with an action that we are not even yet aware that we want to perform? Warning! Warning! - Insert blaring alarms and rotating red lights here - Fasten your existential seat belts because this ride is about to get bumpy! In 1983 a team of researchers led by Dr. Benjamin Libet carried out a now famous experiment to evaluate this question. The researchers recorded the electrical activity in the brains of test subjects which were asked to perform a motor task in a spontaneous fashion, and they also asked the subjects to record the time at which they became aware that they wanted to perform the task. The surprising result of the experiment was that, while the awareness of wanting to perform the task preceded the actual task as expected, the electrical cerebral activity associated with the motor task performed by the subjects preceded by several hundred milliseconds the reported awareness of wanting to perform the task! This amazing experimental result has been replicated by other researchers employing different methodologies. One study employing magnetic resonance to image brain activity stablished not only that the brain activity associated with the task is detected in some brain centers up to 7 seconds before the subject becomes aware of wanting to perform the action, but also that decisions based on choosing between 2 tasks could be predicted from the brain imaging information with an accuracy significantly above chance (60%). Delving even deeper into the brain, another group of researchers recorded electrical activity from hundreds of single neurons in the brains of several subjects performing tasks and found that these neurons changed their firing rate and were recruited to participate in generating actions more than one second before the subjects reported deciding to perform the action. The researchers could predict with 80% accuracy the impending decision to perform a task, and they concluded that volition emerges only after the firing rate of the assembly of neurons crosses a threshold.  The interpretations of these types of experimental results have triggered a debate that is still ongoing. The most unsettling interpretation is that there is no free will (i.e. your brain decides what you are going to do before you even become aware you want to do it). However, there are many critics that claim that there are technical flaws in the experiments, that the data is being overinterpreted, that the electrical activity detected is merely preparative with no significant information about the task, or that it is a stretch to extrapolate from a simple motor task to other decisions we make that are orders of magnitude more complex. In any case the question of whether free will exists is in my opinion irrelevant because our society cannot function under the premise that it doesn’t. What interests me from the point of view of the astounding hypothesis, is the possibility that the awareness of wanting to perform an action before we perform it is merely an illusion created by the brain. This notion is not farfetched. As I explained in an earlier post, the brain creates internal illusions for us that we employ to interact with reality. Colors are not “real”, what is real is the wavelength of the light that hits our eyes. What we perceive as “color” is merely an internal representation of an outside reality (wavelength). The same goes for the rest of our senses. As long as there is a correspondence between reality and what is perceived, what is perceived does not have to be a true (veridical) representation of said reality. Consider your computer screen. It allows you to create files, edit them, move them around, save them or delete them. However, the true physical (veridical) representation of what goes on in the computer hard drive when you work with files is nowhere near what you see on your screen. This is so much so, that some IT professionals refer to the computer screen as the “user illusion”. So, much in the same way that the brain creates useful illusions like colors that allow us to interact with the reality that light has wavelengths, or the computer geeks create user illusions (file icons) that allow us to interact with the hard drive, could it be that the awareness of wanting to perform actions, in other words, becoming conscious of wanting to do something, is just merely an illusion that the brain creates for the mind to operate efficiently? We are still in the infancy of attempts to answer these questions, but what is undeniable is that the evidence indicates that there is substantial brain activity taking place before we perform actions that we are not even yet aware we wish to perform, and that this brain activity contains a certain degree of information regarding the nature of these actions. As our brain imaging technology and our capacity to analyze the data gets better, will we be able to predict with certainty what decision a person will make just by examining their brain activity before they become aware they want to make the decision? It’s too early to tell, but from my vantage point it seems that so far Crick’s astonishing hypothesis is looking more and more plausible. The image of the cover of the book The Astonishing Hypothesis is copyrighted and used here under the legal doctrine of Fair Use. The Free Will image by Nick Youngson is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed