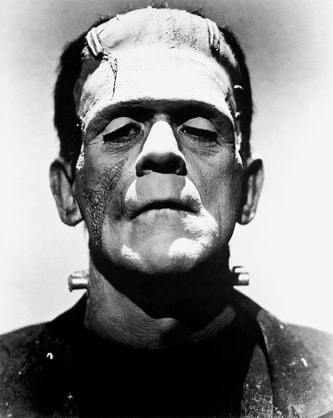

More than 200 years ago Marie Shelley published her novel “Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus” which told the tale of a scientist playing God and the nasty consequences that ensued. The story became a literary success which captured the imagination of generations and moved into the realms of theater and then film and television almost as soon as these were invented. It was in the 1931 film directed by James Whale (in which the master of horror Boris Karloff played the monster) that the current view of what the monster looks like was cemented in popular culture. Since then, all visual references to the Frankenstein monster have those emblematic electrode bolts sticking out of the sides of his neck. It was also in this movie that the actor Colin Clive embodied in popular culture the image of the mad scientist with his deranged scream of, “It’s alive!”. It is interesting that most people associate the name Frankenstein with the monster, even though the monster never had a name. Frankenstein is the name of the scientist who created it: Victor Frankenstein. It is also interesting that Frankenstein’s creation is considered to be the monster when reality is a bit more complex. This is described in a clever joke that differentiates knowledge from wisdom. Knowledge is understanding that Frankenstein is not the monster. Wisdom is understanding that Frankenstein is the monster. But one of most remarkable aspects of Frankenstein as a cultural phenomenon is how we have ended up using not only the full name but also the word “Franken” as a prefix. Anything preceded by the prefix “Franken” can mean several things such as something monstrous or deformed, or something made out of many parts, or something dead or dormant which has been reanimated, or a created entity that is unusual in some real or imagined negative way or that turns on its creator. I will go over some examples in this post. In the 1980s, the CIA supported and trained Islamic rebels (the mujahedin) fighting the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan including Osama Bin Laden. The late president of Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto, warned President George H. W. Bush that he was creating a Frankenstein. And sure enough, after the rebels defeated the Soviets, they turned on the US. with ever increasing acts of terrorism, culminating with the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center Towers and the Pentagon. The large hurricane that wreaked havoc upon the East Coast of the United States in 2012 killing 280 people and causing 65 billion dollars in damage, Hurricane Sandy, was dubbed a “Frankenstorm”. In the cartoon SpongeBob Squarepants, there is a 2002 episode in which SpongeBob creates a doodle bearing his likeness that acquires a life of its own and runs amok causing all sort of mischief. The name of the episode is, of course, “Frankendoodle.” When my daughter was in middle school, she brought home a project from her ceramics class. It was a strange dark green shape with two knobs sticking out at right angles and what appeared to be stiches on its surface. I asked her what it was and she replied, “It’s a Frankenapple!” In the 1990s, several dog breeders began crossing purebred dogs and creating new breeds (for example crossing a poodle with a Labrador will yield a labradoodle). These new dog breeds were called “designer dogs” and unleashed a craze to buy these expensive canines which were dubbed Frankendogs by those people scandalized with the practice. In 2002 the invasive Asian snakehead fish made the news when several of them were found in a pond in Crofton, Maryland. Since then, the snakehead has become established wreaking havoc in the ecosystem of the Potomac River watershed. Its voracity, resilience, and ugliness have earned it the name of “Frankenfish”. Hollywood decided to commemorate this event by releasing a movie with an eponymous title. The punk rock band The Dead Kennedys put out a record in 1985 called “Frankenchrist.” Inside the record cover they ill-fatedly included a poster by artist Hans Rudolf Giger entitled “Penis Landscape.” In a true Frankenstein-like fashion the resulting obscenity trial nearly drove the band’s record label out of business. In 2012, a teacher wrote an article about an unsuccessful attempt to conduct a reading class employing e-books. The title of her article? Frankenbook. In 2015 a large 30,000-year-old virus was discovered in Siberia, and researchers planned to revive this pathogen which was dubbed a “Frankenvirus”. In 2012, filmmaker extraordinaire Tim Burton brought to the screen a story about a boy named “Victor” who brings his dog “Sparky” back to life with a lot of unintended consequences. The name of the movie? Frankenweenie! The folks at the Urban Dictionary define Frankenjob as “a job consisting of a variety of different, often largely unrelated, tasks and duties, often resulting from corporate downsizing, restructuring or layoffs that cause many people's jobs to be combined into one.” They give the following example: After all those layoffs, management gave Fred so many different people's work, he's got a real Frankenjob now. Environmentalist and consumer advocacy groups often refer to genetically modified foods as Frankenfoods and to genetically modified crops as Frankencrops. Related to this, a rumor got started in 2000 that involved the Kentucky Fried Chicken chain of restaurants. When the franchise began calling itself “KFC” to reflect that it offered a wider variety of food choices, the rumor originated that they did this because they were not serving chicken anymore in their restaurants but a genetically modified organism that they could not legally call chicken. So what were they rumored to be serving? Frankenchicken! In a 1990 film a medical school dropout endeavors to bring back to life his dead girlfriend using parts obtained from dead New York prostitutes. The result? Frankenhooker! The examples above are some of the many uses of the frankenprefix. Have you heard about a particular use that I have not listed here? Please leave a comment and let me know. The photograph of Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster from Universal Studios is in the public domain.

0 Comments

Some individuals want to be professional mad scientists, but they are unwilling to go through the arduous scientific training that all scientists have to complete. Even mad scientists need to know their stuff, and they have to be able to distinguish fact from fiction to a certain extent. Take for example the case of Frank Nicolas Stein. This guy was an amateur scientist who initially decided to go by the book. He bought an old castle towering above a quaint small village. He got himself an assistant with a limp and a hump on his back (except his name was Steve, not Igor). He and Steve raided the local cemetery for freshly interred corpses, stitched parts of them together (including, of course, an Abby-Normal brain) to form a deformed creature, and finally zapped it with a zillion volts during a ghastly storm. The result? Nothing. The whole premise behind the Frankenstein story is a myth. Dead tissue exposed to electric current does not come back to life. It remains as dead as a dead parrot. Frank realized that he had wasted all those hours rehearsing in front of the mirror screaming over and over, “It’s alive!” and laughing manically. To add insult to injury he was captured, not by an angry mob with pitchforks and torches, as would have happened to any deserving mad scientist, but rather just by the local sheriff and his deputy. Mr. Stein was sent to jail for a year (Steve was just slapped for 2 minutes and then let go). Imagine the humiliation! But Frank plotted his revenge. When he left jail, he decided he would poison the villagers to make them pay for what they did to him. To this end he purchased in the black market two of the most lethal substances known to mankind. The first of these was the extremely toxic chlorine gas which was used as a chemical weapon during World War I. The second was elemental sodium, a compound so reactive that its mere interaction with water produces dramatic explosions that release a huge amount of heat. Frank’s master plan was that he would combine these two toxic substances into a lethal mix the likes of which the world had never seen, and he would release it into the village’s drinking water! Frank rehired Steve, and also hired a few of his ne'er-do-well friends. For several days they toiled away in an abandoned warehouse mixing large quantities of both substances which to his delight produced spectacular ceiling-high yellow flames! Such was the power of this accursed mix of chemicals. The reaction yielded a white product which he, mindful of its deadly power, carefully collected and stored in vacuum sealed flasks. When his dastardly work was done, Frank transported a truck loaded with the white chemical to the source of the town’s drinking water at a late hour of the night. He and his minions broke into the facility, subdued its only guard, and proceeded to release the poison into the water while laughing maniacally. The result? Nothing. The people of the town woke up noticing that their drinking water tasted “salty”, but that was about it. No deaths, no poisoning, not even an upset stomach. The sheriff was called, and he and his deputy made their way to the water plant in time to arrest Frank, who upon seeing them screamed, “Not you again!” Mr. Stein was once more sent to languish in jail, humiliated and despondent (this time though, Steve and his cronies kept him company). What happened? Sodium is indeed extremely reactive because the sodium atom has a free electron in its outer shell that it will share with any other chemical compound that accepts it. Chlorine, on the other hand is a very strong oxidizing agent, which means it will take an electron away from other chemicals. So when you put them together, sodium very naturally cedes its outermost electron to chlorine in a reaction that releases a lot of heat. The result of this reaction is a sodium atom lacking an electron and thus bearing a positive charge, and a chlorine atom with an extra electron which confers it a negative charge. This transformation dramatically changes the nature of these elements. The explosive sodium and the toxic chlorine become the innocuous sodium chloride, in other words: table salt. This was the white powder that Frank released into the village’s drinking water supply! This story is meant to illustrate that we should not make assumptions regarding the properties of a compound just based on the properties of a few of its components in isolation. However, many people do not understand this concept. In 2017 a video showing a towering structure emerging from an amalgamation reaction between a block of aluminum and a drop of mercury went viral on the internet (check the dramatic effect beginning at 2 minutes). Then an anti-vaccine Facebook page posted a scare-mongering rhetorical question alluding to the video: “Hmmm… What mandated medical injections also combine thimerosal (mercury), which still remains in several vaccines and aluminium, used in almost all vaccines? It’s time to reject vaccine MYTH and embrace the truth.” This post made a reference to 2 components of some vaccines, a mercury derivative called thimerosal, and an aluminum derivative called aluminum phosphate. The implication of course is that if these 2 things (mercury and aluminum) can produce the reaction shown in the video, what awful things will happen inside your body if you get inoculated with vaccines that contain these 2 items? The short answer: nothing. This anti-vaccine post was debunked by sites like Snopes which, among other arguments, pointed out that the reaction in the video had been between elemental mercury and elemental aluminum. However, the mercury and aluminum components of vaccines are not pure elements but rather chemical derivatives. Much in the same way that the sodium and the chloride in sodium chloride have chemical properties that are very different from those of the pure elemental forms (sodium and chlorine), the mercury in thimerosal and the aluminum in aluminum phosphate behave very differently from the pure forms of these elements. This is not the first time that anti-vaccination proponents have raised false alarms, but with respect to this one they should have read a chemistry book, or at least asked, Frank. He has learned this the hard way! Mad scientist caricature by J.J. used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license. The trope of the mad scientist has been around for a while, and many people, including scientists, indulge in it as a joke, although some claim it has a grain of truth to it. The classical image of the mad scientist was cemented by the 1931 film Frankenstein, directed by the legendary James Whale. In this movie, the scientist Henry Frankenstein, played by actor Colin Clive, assembles a body from parts stolen from graveyards and proceeds to jolt it with electricity, infusing it with life. Frankenstein’s manic scream “It’s alive!” has become a cultural icon that has been both referenced in academic literature and parodied in popular culture. What is less quoted in the popular realm is what he says afterwards: “Now I know what it feels like to be God!” This seems to be at the heart of the concept of the mad scientist: the original sin, eating the fruit from the tree of knowledge, being like God. And what better way to be like God than to create life? Of course, Frankenstein was barking mad, but don’t sane scientists have a little bit of Frankenstein in them when they seek the knowledge of the inner working of nature and the universe? Doesn’t scientific discovery make scientists feel a little bit like Gods? My response to this question is that it is irrelevant. Scientists are humans, and their behavior during the process of discovery or creation is as complex as that of any other human. In my opinion the important thing is that regardless of what scientists “feel”, they are expected to follow the scientific method. The truth is that Frankenstein’s research, even by the standards of his time, was not very scientific. What was his question? What was his hypothesis? What was the rationale for the whole enterprise? Why try to create life? Why work in isolation without seeking advice from other scientists? Frankenstein was no more a scientist than an astrologer is a scientist. He was not following the scientific method. However, as it turns out, back in 2010 a group of real scientists led by Craig Venter of the Human Genome fame succeeded in creating life. It is instructive to compare what they did with the modus operandi of their fictional counterpart.  In an effort that took more than a decade of solving seemingly unsurmountable technical problems, Venter and his group synthetized a modified chemical copy of the genome of a microorganism called Mycoplasma mycoides and inserted it into a cell of a different species called Mycoplasma capricolum. They engineered the M. mycoides genome in such a way that it would get rid of the endogenous M. capricolum genome. So they ended up with an M. capricolum cell which contained a synthetic M. mycoides genome. The synthetic genome took over the host cells which began multiplying. Unlike most living things which are made by strands of DNA that come from other living things, here, for the first time in history, a life form had been created using a strand of DNA made in a lab and designed by a computer! No one in Venter’s group broke out into maniacal laughter and screamed “It’s alive!”, or claimed to have experienced “what it feels like to be God” (at least publicly). They were all, of course, aware of the philosophical issues revolving around what they were attempting to do, but the point of the project was to answer some very specific scientific questions such as whether the information present in the genome was enough to reproduce a living organism, or whether something else was required. During the whole research process Venter’s group shared information about what they were doing and requested input from other scientists. Additionally, even before performing the first experiments, they asked a team of independent scientists to evaluate the risks, challenges, and ethics involved in creating a new species in the laboratory. The ethics team spent 2 years carrying out this evaluation and then openly shared their conclusions. Venter’s work was not merely an academic exercise, as it led to many practical applications. For example, thanks to the technology developed we have the capacity to quickly sequence the genome of a virus and send the information about the sequence over the internet to centers where the viral genome will be synthesized and used to drive the creation of modified viruses to make vaccines. This sober approach to the scientific enterprise may be more boring than the deranged approach of the quintessential mad scientist, but in real science this is the way things work. Photograph of Craigh Ventor is from the Chemical Heritage Foundation reproduced here under a Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed