|

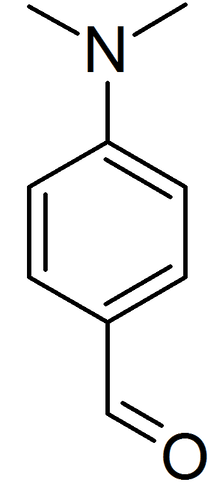

11/22/2018 Chemical nomenclature and Asimov on Speaking Gaelic - The Irish Washerwoman and Para-dimethylaminobenzaldehydeRead NowFor non-chemists, and even for many scientists, chemical names can be particularly vexing. Take for example the compound para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (pronounced: PA-ruh-dy-METH-il-a-MEE-nohben-ZAL-duh-hide). I mean, seriously, if the average person were walking down the street and somebody yelled “PA-ruh-dy-METH-il-a-MEE-nohben-ZAL-duh-hide” at them, they would probably reply with anything from “Watch your language” to “Up yours”! As it turns out this chemical is also known as Ehrlich's reagent, after the German Nobel Prize winning Physician who discovered it, Paul Ehrlich. Para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde has a long and distinguished history where it has been used in various analytical, chemical, biochemical, and industrial applications. So why not call it Ehrlich’s reagent and simplify things? Well, some scientist do, but the advantage of using the chemical name is that any scientist familiar with the rules of chemical nomenclature will know what compound you are talking about even if they have never seen it before in their lives. This is because every single syllable in para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde has information regarding the chemical groups that make up this compound and how they are bonded together. And not only that, each of these words has a fascinating history as to their origin and the many permutations that they went through before coming to symbolize the chemical entities they represent today. Still, you may argue that para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde sounds Greek to you; or perhaps “Gaelic”?  Isaac Asimov Isaac Asimov Back in March of 1963, the science fiction writer extraordinaire Isaac Asimov published a remarkable article in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Although the article was referred to by the editors as “one of Dr. Asimov’s insufferably tedious articles”, it traced the amazing story of the origin of each section of the name para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde. In the article, Asimov relates that way back when he was a practicing scientist he went to the reagent shelf to search for this chemical and asked a person if they had some. This person tried to be whimsical at his expense (which was a no-no when it came to the great Isaac Asimov) by singing the name of the chemical to the tune of the traditional Irish jig “The Irish Washerwoman”. Asimov, of course, put him in his place, but he couldn’t shake the melody from his head, and found himself singing over and over para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde to the tune of the "Irish Washerwoman", sometimes out loud. Once he did this in an office in the presence of an Irish receptionist, who then commended him for singing the words of the melody in the original Gaelic language! Asimov then undertakes the task of teaching his readers to “speak Gaelic” by which he means to pronounce chemical names. For this he dives into the rich and complex history of the chemical nomenclature behind para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde that spans several centuries of human cultural and technological developments. It is a fantastic tale that takes the reader from the islands of Sumatra and Java in Southeast Asia, to the temples erected in Egypt to the God Amun, and to the laboratories of leading chemists in Germany, England, Sweden, and France. It is a story involving women’s makeup and camel dung, Greek prefixes and philosophers, Arabic traders and alchemists, and of course, wood alcohol. I encourage you to read the original article in page 72 of the magazine. It is a delightful piece that reveals the sheer wonder behind what otherwise appears to be a cryptic and boring science word, and which also showcases the mastery and scientific knowledge of Asimov. Remember that he wrote this in 1963 before the internet was available to search for information. In view of the foregoing, it is only fitting that John Carroll has composed a drinking song (The Chemist’s Drinking Song) inspired by Asimov’s story to the tune of “The Irish Washerwoman” with lyrics that incorporate the word: para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde. In case the song is too fast for you to appreciate, there is also a slower version with slightly altered lyrics and some visuals that you can watch below. Asimov passed away in 1992, but his wit and brilliance are still with us in the 500 plus fiction and non-fiction books that he wrote or edited. The chemical formula by Rifleman 82 is in the public domain. Asimov’s Photograph from the New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection is in the public domain.

2 Comments

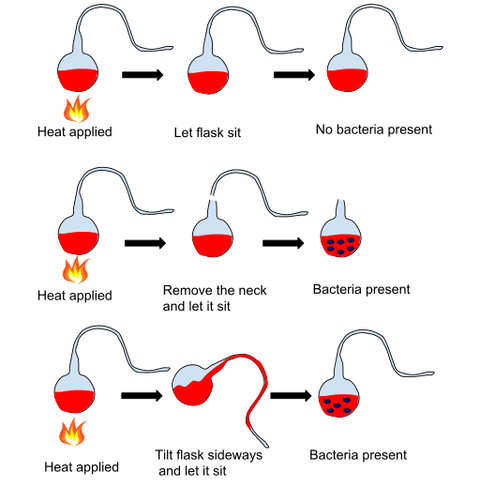

There is an old science joke where a scientist trains a spider to jump when a bell is rung. The scientist then removes a leg from the spider under anesthesia and makes sure the spider heals. The scientist proceeds to ring the bell again. Even with one less leg, the spider manages to jump in response to the sound. The scientist repeats this procedure removing a leg each time and ringing the bell, and the spider manages to “jump” in response (at least as best as it can). This goes on until the spider is legless. After repeatedly ringing the bell and getting no response, the scientist concludes that the spider without legs becomes deaf! What is ironic about this silly joke is that scientists have recently discovered that indeed the spider's ability to detect sound is based on hairs present on its legs. So you see, the scientist in the joke arrived at the right conclusion (legless spiders become deaf) although for the wrong reasons! The above got me thinking about whether there are any examples of real scientists who got it right but for the wrong reasons. As it turns out there are a several examples, and one of the most famous of these is the French Chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur and the idea of spontaneous generation. In the 19th century, the notion of spontaneous generation came under attack. This ancient notion posited that life continuously arises from non-life. At the time, the fact that nutrient broths exposed to the air would develop microorganisms was considered evidence for spontaneous generation. However, although a consensus had begun developing that life could only arise from preexisting life, and that the microorganisms that swarmed in nutrient broths represented nothing but airborne contamination, many scientists still defended the idea of spontaneous generation.  Into this scene entered Pasteur, and he performed his famous experiments where he boiled sugared yeast-water in a flask that remained exposed to the environment through a very long neck (swan-necked flasks). Pasteur found that the nutrient mix inside the flasks remained uncontaminated, presumably because any airborne organisms stuck to the neck of the flasks, but as soon as he broke the neck of the flasks or tilted them, bacteria and mold stated growing. He repeated these experiments with sterile liquids that did not have to be boiled, like blood or urine obtained directly from the bladder, and attained the same result. To great acclaim by the scientific community he declared that he had demonstrated that only germs in the air can produce the growth observed in these nutrient mixes, therefore life can only arise from life. However, a few scientists challenged Pasteur. These scientists, using different nutrient mixes like hay infusions or potash solutions derived from urine, found that microorganisms arose in nutrient broths even after they had been boiled and isolated from the environment in a manner similar to Pasteur’s procedure. They claimed their results proved that, at least in these different nutrient infusions, life arose by spontaneous generation and challenged Pasteur to repeat their experiments publicly. What did Pasteur do? He ignored their results, or dismissed them claiming they were due to sloppy methodology, and refused to repeat their experiments. Pasteur prevailed thanks to his connections, his fame, and for being against spontaneous generation at the right time. As far as he and his supporters were concerned the matter had been settled. So who was right? Even though Pasteur acted very unscientifically in addressing his critics, he was indeed right, but for the wrong reasons. Spontaneous generation does not occur, but Pasteur was wrong to ignore or dismiss his critics’ results, because these results were true. It would be more than a decade after Pasteur performed his experiments before it was understood that there are bacteria that produce spores which can survive heating at very high temperatures. It is likely that Pasteur’s infusions of sugared yeast-water did not contain these bacteria, but that the infusions of hay and potash employed by his critics had these spore-forming bacteria. Therefore, even after boiling these infusions at high temperature, Pasteur’s critics found these nutrient mixes became contaminated when the spores became active after the temperature had returned to normal. The critics were wrong in claiming their results supported spontaneous generation, but at the time the complete truth was not known, and there was enough ignorance to go around.  Pasteur Pasteur Ironically, if Pasteur had behaved like a true scientists and repeated his critic’s experiments, he would have had to face conflicting evidence that could have led him to admit that spontaneous generation was possible in some cases. This could have muddied up the field and hindered progress, but by ignoring valid data, he avoided an incorrect interpretation, and arrived at the right conclusion. Such is the complexity of the interaction between reality and the human mind in the context of scientific discovery. Pasteur moved on to greater accomplishments (and more controversy, but that’s another story) where he was proven right many times. Today he is remembered for the process to prevent bacterial growth in substances like wine and milk (pasteurization), his many contributions to the prevention of disease which saved countless lives, and the founding of the Pasteur Institute which over the years has had a huge impact on health science worldwide with 10 of its scientists being awarded Nobel Prizes. Nevertheless, in the case of spontaneous generation, he was right but for the wrong reasons! My reference for Pasteur’s story is John Waller’s excellent book: Fabulous Science. Image of Pasteur’s experiment by Kgerow16 is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license. The image of Pasteur by Paul Nadar is in the public domain. In this post I am going to rant a little, so please indulge me. Have you seen the videos of some animals that in nature would otherwise be mortal enemies, or predator and prey, frolicking around or snuggling each other? Some people would point out how it fills our hearts with sheer bliss seeing these creatures so happy and content, far removed from the ghastly carnage of “nature, red in tooth and claw”. Look, I get it. I’m human. I like cute, warm, snuggly, lovey-dovey stuff too. Watching these videos brings a smile to my face, and I have liked them and shared them on media. However, when I read some of the comments in the threads of these videos, I feel dismayed. In these comments these animals are labelled “pure” and “moral”, and the case is made that we should learn from them to live in harmony with each other. It’s as if this type of animal behavior is proof that love and friendship can overcome everything, and that in the end the lion will lie down with the lamb. I don’t like to puncture anyone’s bubble, but I am compelled to point out that this is a highly artificial situation. Many of these animals are removed from their natural environment and raised together, and/or they are all well fed and well taken care of. Many of these animals have not had to kill or escape predators to survive, and in fact some of them are the result of generations of selective breeding to make them docile. Furthermore, in the case of carnivores, what is not shown in the videos is that they are fed meat or meat-based foods. The “ghastly carnage” has already taken place at the slaughterhouse. Countless hapless farm animals have given up the ghost so that these animals could be well nourished and in the mood to be cute, warm, snuggly, and lovey dovey-for the videos. The truth is that, left alone to themselves, the lion and the lamb will NEVER lie down together because lions and other felines like cats are obligatory carnivores. The particular evolutionary processes that gave rise to these animals have made them dependent on nutrients found in meat. In their natural environment, if carnivores don’t eat meat they die. If these nutrients are included in a diet, even a synthetic one, they can survive, but this requires human intervention. And this is what these videos are all about: human intervention. As humans beings we tend to extrapolate our emotions to animals, and there may even be neurological reasons for why we do this. Nevertheless, while there is ample evidence that many species of animals are not merely robots driven by instinct, and that they display what we would call “emotions”, it has to be understood that it is difficult to establish equivalence between human and animal emotions, or even behaviors for that matter. On a pleasant day we may walk down the street whistling a tune because we feel particularly cheerful, but a bird on a nearby branch may be singing just to attract a mate. Not content with extrapolating emotions to animals, we also extrapolate our values. Humans are the only species on Earth to have declared that they have inalienable rights, and to have stated that certain behaviors are virtuous and inherently good while others are deplorable and inherently evil. In principle, we should recognize that the world of nature is removed from this convention, but it seems that many people can’t avoid assessing animal behavior in terms of their own values. If the friendship brought about by human intervention on animals that in the wild are predator and prey is “good”, then the natural situation must be on some level inherently “bad”. Therefore, of course, it follows that killing (what predators do) is wrong, and hunters, animal or human, are “bad”.  The extrapolation of human emotions and values to animals reaches its pinnacle in works of fiction where animals are anthropomorphized. One prime example of this is the Walt Disney movie Bambi. Much has been written about the problems with this movie, and many of us who saw it when we were kids have never forgotten the killing of Bambi’s mother by human hunters. Truly, anyone who can commit this atrocious murder for sport is the epitome of evil - except that if deer behaved anywhere near how they are depicted in the movie, in other words: like humans, we would not be killing them! Humans are predators. If you consume any type of meat, you either kill animals or have others do it for you, and most people would argue that there is nothing wrong with that. It’s what predators do for heaven’s sake! It’s neither good nor bad, it’s natural. We can have discussions about animal rights, about what species should be protected, about how animals should be treated, and so forth, and that is all well and good, but we have to stop viewing animals through the prism of our emotions and our values; especially animals in situations such as the ones featured in internet videos. In my opinion, the animals in these videos are nothing but a parody of their natural brethren. This is not their normal state. This is not “nature”, and in this sense we cannot learn anything from them. Much in the same way that humans exploit animals for food, clothing, or research, these animals are exploited for their cute, warm, snuggly, lovey-dovey-ness to elicit oohs and aahs (and video likes). Of course, there is nothing wrong with that, but let’s call a spade a spade, can’t we? The screenshot from the 1942 trailer for Bambi is in the public domain.  A lot of books, movies, and even video games employ the motif of the living dead. All of this is, of course, fiction, but have you ever wondered whether there is something to it? In the Haitian Voodoo religion, zombies are believed to be corpses that have been reanimated through witchcraft by a sorcerer called a “Bokor.” These zombies are nothing like the ones shown in movies like “Night of the Living Dead”, but still their existence has always been the mainstay of myth and legend. In 1982 the peculiar case of Clairvius Narcisse was brought to the attention of Drs. Nathan Kline and Lamarque Douyon. Narcisse had died and been certified as dead by an American doctor working in Haiti. The thing is that 18 years after his death he showed up in his village very much alive. He claimed that he had been paralyzed, declared dead, and buried alive. Then a Bokor disinterred him and made him work on his plantation. Drs. Kline and Douyon studied his case carefully and concluded that the man was indeed who he claimed to be. At the request of Dr. Kline, Wade Davis, a Harvard graduate student in ethnobotany, travelled to Haiti to try to study what components go into the potions used by Bokors to make zombies. As a result of his studies he claimed that zombies were a reality and even put forward a scientific explanation of their existence! Wade found that one of the common ingredients in the zombie poison is the puffer fish. The internal organs of this fish contain a poison called tetrodotoxin (TTX). Although TTX can kill, in small amounts it can paralyze a person while they remain conscious. In Japan where a similar fish (the fugu) is a gourmet delicacy, there are stories of people that ate the fish prepared improperly, became paralyzed, and were almost buried alive after being declared dead. So the zombification would work like this. The Bokor rubs his potion on a person’s skin or preferably into a superficial wound. If the right amount of TTX gets into the body, the person is paralyzed, declared dead, and buried. The Bokor must then unbury the person before he/she dies from lack of oxygen. The disinterred person is then beaten and fed mind altering drugs (notably the zombie’s cucumber: Datura) to keep them docile. The whole process is reinforced if the person believes that he/she is actually being turned into a zombie. Davis published his findings and theories in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology in 1983 and in the book “The Serpent and the Rainbow” in 1985. Unfortunately, scientists analyzing the zombification powders Davis brought back from Haiti did not find any TTX in them and could not elicit any symptoms of poisoning when they rubbed said powders into the skin of rats. This was followed by a series of attacks and claims and counter claims between Davis and his critics that left his particular theory hopelessly mired in disrepute, and no further attempts have been made to readdress it. But Davis at least raised the possibility that what is called a zombie in these cultures is not, of course, a reanimated corpse, but rather a product of the synergism between mind and chemistry. Other scientists have taken this line of inquiry and studied zombie-like behavior induced by drugs or other agents and documented several cases. This alternative is no doubt less satisfying for all the fans of the nightmarish beings that hunger for the flesh of the living in popular culture. But if you want horror and ghoulish things look no further than the world of nature. What would you think about zombie cockroaches? The Jewel Wasp hunts cockroaches and makes them docile (zombifies them) by injecting venom into their brains. It then leads the cockroach into a place where it will lay an egg on it. The wasp then seals the cockroach in. After a while a larva hatches from the egg and proceeds to eat the drugged insect alive! You can watch the wasp’s grisly work in the video below. It is not anything that George Romero has dreamed up (yet), but it’s real! The photograph of a zombie by Daniel Hollister is used here under an Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed