|

1/29/2021 The Myth of the Unprejudiced Scientist and the Three Levels of Protection Against BiasRead Now As modern science was emerging during the 18th and 19th centuries, ideas regarding how science should be performed also began to take shape. One particular idea posited that scientists subject theories to test, but do not allow their biases to get in the way. Real scientists, it was argued, are unprejudiced, and rather than try to prove theories right or wrong, they merely seek the truth based on experiment and observation. According to this notion, real scientists don’t have preconceptions, and they don’t hide, ignore, or disavow evidence that does not fit their own views. Real scientists go where the evidence takes them. Unfortunately, the romantic notion that real scientists operate free of bias proved to be dead wrong. Scientists, even “real scientists”, are human beings, and like all human beings they have biases that influence what they do and how they do it. While a minority of scientists does engage in outright fraud, even honest scientists who claim they are only interested in the truth can unconsciously bias the results of their experiments and observations to support their ideas. In past posts I have already provided notable historical examples of how scientists fooled themselves into believing they had discovered something that wasn’t real such as the cases of the physicist René Blondot, who thought he had discovered a new form of radiation, or the astronomer Percival Lowell who thought he had discovered irrigation channels on Mars.

It is in part because of the above realization, that scientists developed several methodologies to exclude bias and limit the number of possible explanations for the results of experiments and observations such as the use of controls, placebos, and blind and double-blind experimental protocols. This is the first level of protection against bias. Today the use of these procedures in research is pretty much required if scientists expect their ideas to be taken seriously. However, while nowadays scientists use and report using the procedures described above when applicable, the proper implementation of these procedures is still up to the individual scientists, which can lead to biases. This is where the second level of protection against bias comes into play. Scientists try to reproduce each other’s work and build upon the findings of others. If a given scientist reports an important finding, but no one can reproduce it, then the finding is not accepted. But even with these safeguards, there is still a more subtle possible level of bias in scientific research that does not involve unconscious biases or sloppy research procedures carried out by one or a several scientists. This is bias that may occur when all the scientists involved in a field of research accept a certain set of ideas or procedures and exclude other scientists that think or perform research differently. Notice that above I used the words “possible” and “may”. The development of a scientific consensus within the context of a well-developed scientific theory always leads to a unification of the ideas and theories in a given field of science. So far from bias, this unification of ideas may just indicate that science has advanced. But in general, and especially early on in the development of a scientific field, science is best served not when researchers agree with each other but when they disagree. So the third level of protection against bias that keeps science true occurs when researchers disagree and try to prove each other to be wrong. In fact, some funding agencies may even purposefully support scientists that hold views that are contrary to those accepted in a field of research. The theory is that this will lead to spirited debates, new ways of looking at things, and a more thorough evaluation of the thinking and research methods employed by scientists. However, disagreements among scientists do have a downside that is often not appreciated. While science may benefit when in addition to Scientist A, there is a Scientist B researching the exact same thing who disagrees with the ideas and theories of Scientist A, science may not necessarily benefit when Scientist A and B research something and A thinks that B is wrong and doesn’t have the slightest idea of what he/she is doing, while B thinks A is an idiot who doesn’t understand “real science”. There are a number of examples of long-running feuds in science between individual scientists or even whole groups of scientists. In these feuds, the acrimony can become so great that the process of science degenerates into dismissal of valid evidence, screaming matches, insults, and even playing politics to derail the careers of opponents. But, of course, the problem I have described above is nothing more than the human condition and in this sense science is not unique. Every activity where humans are involved has to deal with bias, but at least in science we can recognize we are biased and implement the three levels of protection against this bias. It may be imperfect, it may be messy, it may not always work, but, being human, that’s the best we can do. Image from Alpha Stock Images by Nick Youngson used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license.

0 Comments

1/23/2021 Election 2020 – In the Absence of Safeguards, How Do We Distinguish Fantasy From Reality? A Scientist’s PerspectiveRead Now Elections are normally not considered a scientific topic. However, when elections take place many scientific questions can be formulated about their outcome. For example, “Which candidate obtained the majority of the votes in a given state or in the overall election?” is a scientific question, as it can be answered by counting the votes. Additionally, and more relevantly to the 2020 election, questions about the integrity of the election can also be formulated as scientific questions. However, and this is the key, BEFORE you ask questions and begin searching for evidence that fraud has taken place, you have to define what would constitute “fraud” (as opposed to mere machine glitches or human error), how said fraud would be detected and investigated, and how much fraud has to be present to label the election as “compromised”. Only then can meaningful questions be asked, evidence procured, and valid conclusions reached. Why is this? Scientists have known from decades of research into the human mind that people with a strong interest in finding evidence for something will find it even if the evidence is not there. Human psychology is such that even people whose intent is honest will filter reality and find patterns where there are none to be found. This is a process akin to finding shapes in the clouds. Defining a priori what constitutes fraud, what should be considered valid evidence for fraud, and how much of it would have to be present to declare the election to have been compromised is an elemental level of protection against human bias. As far as I can tell, Mr. Trump and his team did not do this. Rather they seem to have cast as wide a net as possible which risks ending up with a trove of false positives.

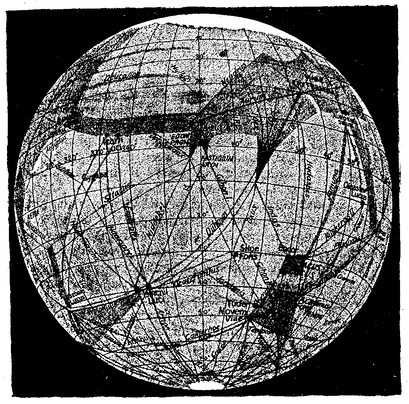

Another level of protection against bias is to recognize that the people best suited to assess whether there is fraud in the election are not those who WANT to find it. This is a very elemental concept in science which has led to the introduction of many controls in the research process. One possible way to control this source of bias is to rely on evaluations of the evidence and the election conducted by people who don’t share your biases, or at least by people committed to place doing their job and following the law above everything else. If enough of these people look at any evidence of fraud presented to them, or assess the procedures followed in the elections and still reach the conclusion that the election was not compromised, then that is an indication that this was indeed the case. Based on the foregoing, agencies such as the Department of Justice and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, along with several dozen courts and fact checkers, plus multiple election officials, state attorney generals, and governors (many of them pro-Trump Republicans) have not found convincing evidence of foreign or domestic interference in the election, or of fraud at a level that would overturn the results of the election. These assessments mentioned above involving many individuals of different political persuasions as well as different courts and agencies should have given Mr. Trump confidence that the election results were fair. Instead, Mr. Trump and his team disqualified these assessments, claiming that the people involved at best were indifferent or incompetent, or at worst had nefarious ulterior motives, and may have even coordinated with each other forming part of a massive conspiracy also involving foreign actors. Over the past few years, I have exchanged many arguments with what I call irrational skeptics. These are people that defend various conspiracy theories ranging from global warming, 911, and COVID-19 severity deniers to antivaccination advocates, creationists, and chemtrail and flat Earth proponents. All these people share the common trait that they are immune to evidence against their ideas, and that any attempt to discredit their ideas will be considered further proof of the existence of a conspiracy. In this sense, I do not see any difference between these irrational skeptics and Mr. Trump and those that support his election fraud claims. Of course, I am not naïve. I know full well that there may be political and other types of motivations behind the claims of the Trump campaign that have nothing to do with a desire to find the truth. But the intention of this post is not to speculate about motivations. My goal is just to address the elections from a scientific perspective. And in that vein, I want to propose a thought experiment. I want you to consider what would have happened if Mr. Biden had contested the results of some of the states he lost employing exactly the same methods and arguments used by Mr. Trump and his team. Suppose that Mr. Biden had selected a team of “colorful” lawyers to find voter fraud. Mr. Biden’s team could have pointed to the fact that Biden was ahead in early voting in some states such as North Carolina but that later this trend reversed, as an indication that something ”strange” happened. They could have gathered affidavits from people that thought they had witnessed something suspicious or irregular going on. They could have interpreted every glitch in the system or any clerical error in the worst possible light. They could have interpreted videos of election workers going about their jobs to suggest irregularities and edited portions of the videos in suggestive ways to make their case. They could have relied on testimonials of selected “experts” that exaggerated their credentials. They could have put forward statistical analyses of voting data based on questionable assumptions. They could have alleged that their observers were not allowed enough access to the vote counting process. They could have even named their lawsuit the “Medusa” lawsuit (Kraken/Medusa - get it?). My question then is: If Mr. Biden and his lawyers had searched for evidence of voter fraud in some of the states he lost employing these sloppy or questionable procedures, would they have “found” evidence of voter fraud of a magnitude and nature similar to that found by Mr. Trump’s lawyers in other states? The point of this exercise is to consider whether, in the absence of safeguards against human bias, the normal impressions people derive from their assessment of reality, coupled to the glitches and mistakes present in any election, can be spun to construct a narrative of fraud. I will leave it up to you to answer this question. But if your answer is “Yes”, then it should be obvious that unless rigorous and well-defined procedures are employed to analyze the integrity of a process such as elections, it is impossible to distinguish fantasy from reality. Scientists know this to be true for science which is why they use these procedures. Assuming there is an honest interest in finding the truth, why can’t we accept the same procedures are necessary for evaluating the integrity of elections? And if we accept this is the case, why can’t we accept that any investigation that was carried out without following these procedures is not trustworthy and its premises are questionable? Election 2020 image by conolan from Pixabay is in the public domain.  The Raising of Lazarus The Raising of Lazarus The drug hydroxychloroquine is being tested against COVID19, but there is still no compelling scientific evidence that it works, let alone that it is a “game changer” in our fight against COVID19. However, the president has claimed that there are very strong signs that it works on coronavirus, and the president’s economic adviser, Peter Navarro, has criticized the infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, for questioning alleged evidence hydroxychloroquine works on COVID19. The French researcher, Dr. Didier Raoult, who performed the original trial of hydroxychloroquine that generated all the current interest in the drug, now claims that he has treated 1,000 patients with COVID19 with a 99.3% success rate. In the news, I have read descriptions of patients that have recovered after being administered hydroxychloroquine in what has been called a “Lazarus effect” after the Biblical story where Jesus brought Lazarus back from the dead. So what is a scientist to make of this? I have acknowledged that science cannot operate in a vacuum. I recognize something that Dr. Fauci has also recognized, and that is that people need hope. However, as Dr. Fauci has also stated, scientists have the obligation to subject drugs to well-designed tests that will conclusively answer the question of whether a drug works or not. There seems to be a discrepancy between the quality of the evidence that scientists and non-scientist will accept to declare that a drug works, and there is the need to resolve this discrepancy. People anxiously waiting for evidence regarding whether hydroxychloroquine works, will understandably concentrate on patients that recover. Therefore they are more prone to make positive information the focus of their attention. Any remarkable cases where people recover (Lazarus effects) will invariably be pushed to the forefront of the news, and presented as evidence that the drug works wonders. What people need to understand, is that these “Lazarus” cases always occur, even in the absence of effective interventions. We all react to disease and drugs differently. Someone somewhere will always recover sooner and better than others. How do we know whether one of these Lazarus cases was a real effect of the drug or a happenstance? Isolated cases of patients who get better, no matter how spectacular, are meaningless. Scientists look at people who recover from an illness after being given a drug in the context of the whole population of patients treated with the drug to derive a proportion. The goal is then to compare this proportion to that of a population of patients not given the drug. Scientists also have to consider both positive and negative information. For the purposes of determining whether a drug works, patients that don’t recover are just as important to take into account as those that do. What if a drug benefits some patients to a great extent but kills others? Depending on the condition being treated, it may not be justified to use this drug until you can identify the characteristics of the patients that will be benefited by the drug. To do all the above properly, you need to carry out a clinical trial. No matter how desperate people are, and no matter how angry it makes them to hear otherwise, this is the only way to establish whether a drug works or not.  Hydroxychloroquine Hydroxychloroquine Once we accept the need for a clinical trial to establish whether a drug works, another issue is trial design. A trial carried out by scientists is not valid just because it happened. There are optimally-designed trials and suboptimal or poorly designed trials. There are several things a optimally designed trial must have. 1) The problem with much of the evidence regarding hydroxychloroquine is that it has been tested against COVID-19 in very small trials, and clinical trials of small size are notorious for giving inaccurate results. You need a large enough sample size to make sure your results are valid. 2) Another problem is: what you are comparing the drug against? Normally, you give the drug to a group of patients, and you compare the results to another group that simultaneously received an inert dummy pill (a placebo), or at least to a group of patients that received the best available care. This is what is called a control group. In many hydroxychloroquine trials there were no formal control groups, but rather the results were loosely compared to “historical controls”, in other words, to how well a group of patients given no drug fared in the past. But this procedure can be very inaccurate as there is considerable variation in such controls. 3) Another issue is the so called placebo effect. The psychology of patients knowing that they are being given a new potentially lifesaving drug is different from that of patients that are being treated with regular care. Just because of this, the patients being given the drug may experience an improvement (the so called placebo effect). To avoid this bias, the patients and even the attending physicians and nurses are often blinded as to the nature of the treatment in the best trials. Most hydroxychloroquine studies were not performed blind. 4) Even if you are comparing two groups, drug against placebo or best care, you need to allocate the patients to both groups in a random fashion to make sure that you do not end up with a mix of patients in a group that has some characteristic that is overrepresented compared to the other group, as this could influence the results of the trial. Most hydroxychloroquine studies were not randomized. These are but a few factors to consider when performing a trial to determine whether a drug works. These and other factors, if they are not carefully dealt with, can result in a trial yielding biased results that may over or underestimate the effectiveness of a drug. Due to budget constraints, urgency, or other reasons, scientists sometimes carry out very preliminary trials that are not optimal just to give a drug an initial “look see” or to gain experience with the administration of the drug in a clinical setting. But these trials are just that, preliminary, and there is no scientific justification to base any decision regarding the promotion of a drug based on this type of trials. The FDA recently has urged caution against the use of hydroxychloroquine outside the hospital setting due to reports of serious heart rhythm problems in patients with COVID-19 treated with the drug. A recent study with US Veterans who were treated with hydroxychloroquine found a higher death rate among patients who were administered the drug (to be fair, this study was retrospective and therefore did not randomize the allocation of patients to treatments, so this could have biased the results). Even though I am skeptical about this drug, I would rather save lives than be right. I really hope it works, but the general public needs to understand that neither reported Lazarus effects nor suboptimal clinical trials will give us the truth. The 1310-11painting The Raising of Lazarus by Duccio di Buoninsegna is in the public domain. The image of hydroxychloroquine by Fvasconcellos is in the public domain.  There is a joke that illustrates misguided science thinking. A man is in a public area screaming at the top of his lungs. When somebody comes over and enquires why he is screaming, the man replies, “To keep away rogue elephants”. When told that there are no elephants for miles around, the man replies that this is proof his screaming is working. If you think that is silly, consider the following recipe for obtaining mice by spontaneous generation (in other words, without the need for male and female mice): Place a soiled shirt into the opening of a vessel containing grains of wheat. Within 21 days the reaction of the leaven in the shirt with the fumes from the wheat will produce mice. No, I’m not kidding you! For many centuries some of the best minds in humanity believed that life could regularly arise spontaneously from nonlife or at least from unrelated organisms. Some people went as far as outlining procedures to achieve this, such as the one presented above to generate mice supplied by the chemist Jean Baptiste van Helmont. Presumably, this individual (who is no stranger to misguided scientific thinking) placed a shirt in a vessel with grains of wheat, and when he checked 21 days later he saw a mouse scurrying away. Therefore, he concluded that the mix of the wheat and the shirt in the vessel produced the mouse. What the above examples of misguided science have in common is the ignoring of alternative explanations. In the case of the joke, the alternative explanation obviously is that there are no rogue elephants nearby to begin with. In the other case, the alternative explanation is that the mouse came from elsewhere, as opposed to arising from the shirt with the wheat. The best scientific experiment is one carried out in such a manner that alternative explanations for the experimental results are minimized or ruled out altogether. The ideal scientific experiment should only have one possible explanation for the outcome. In order to achieve this, scientists use controls. A control is an element of the experimental design that allows for the control of variables that could otherwise affect the outcome of the experiment. In the case of the joke, the man could stop screaming to see if rogue elephants show up, or he could scream next to an actual elephant to see if screaming works. In the case of the real example, van Helmont could have placed a barrier around the shirt with the wheat to rule out that mice came from the outside. The use of controls in experiments is so commonplace nowadays, that it is really hard to imagine how anyone could even think of performing an experiment without them. However, the modern universal notion of controls as a way of controlling variables to rule out alternative explanations to experimental results did not begin to take shape until the second half of the 19th century, even though scholars claim that strategies to make observations or experiments yield valid results go back further in time to the Middle Ages or even antiquity. In science, the controls that are most often used are those involving outside variables that can affect the results of an experiment. However, the more important and more challenging variables to control are those that arise from within the experimenter.  Illustration of the Canals on Mars by Percival Lowell Illustration of the Canals on Mars by Percival Lowell If the procedure to make an observation or evaluate the results of an experiment depends on a subjective judgement made by the experimenter, as opposed to, for example, a reading made by a machine, then subtle (and not so subtle) psychological factors can influence the result depending on the biases of the experimenter. I have already mentioned the famous case of the scientist René Blondlot who in 1903 announced to the world he had discovered a new form of radiation (N-rays), but it turned out that such radiation existed only in his imagination. Another famous case was that of astronomer Percival Lowell who, at the turn of the 19th century, thought he saw canals on Mars which he considered to be evidence of an advanced civilization. He was a great popularizer of science and he wrote several books about Mars and its inhabitants based on his observations, but the whole thing turned out to be a delusion. To avoid this type of mistake, many experiments that rely on subjective assessments employ a protocol where the observer does not know which groups received which treatments. This is called a blind experimental design.

An additional challenge occurs when a scientists works with human subjects. Psychological factors can have a potent role in influencing the results of medical experiments. Depending on the disease, if patients are convinced that they are receiving an effective treatment, and that their condition will improve, said patients can display remarkable improvements in their health even if they have received no effective treatment at all. To rule out the effect of these psychological factors, scientist performing clinical trials include groups of patients treated with placebos. Placebos are fake pills designed to mimic the actual pill containing the active chemical substance or ineffective procedures designed to mimic the actual medical procedure in such way that the patient cannot tell the difference. To also rule out the influence of psychological factors arising from the doctors giving patients in one group a special treatment, the identity of these groups are hidden from the clinicians. Clinical trials which employ placebos and where both the patients and the clinicians don’t know the identity of the treatments, are called double-blind placebo-controlled trials, and they are the most effective and also the most complex forms of controls. Unfortunately, the use of controls is not always straightforward. I have already mentioned the case of the discovery of polywater which was heralded as a new form of water with intriguing properties that promised many interesting practical applications until someone implemented a control and demonstrated that it was the result of contamination. Sometimes scientists do not know all the variables affecting an experiment, or they may underestimate the effect of a variable that they have deemed irrelevant, or they may misjudge the extent to which their emotional involvement in conducting the experiment may compromise the results. Designing the adequate controls into experimental protocols requires not only discipline, discernment, and smarts, but sometimes also just luck. In fact, some scientists would argue that implementing effective controls is not a science but an art. The art of the control! The Elephant cartoon from PixaBay is free for commercial use. The Illustration of Mars and its canals by Percival Lowell is in the public domain. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed