|

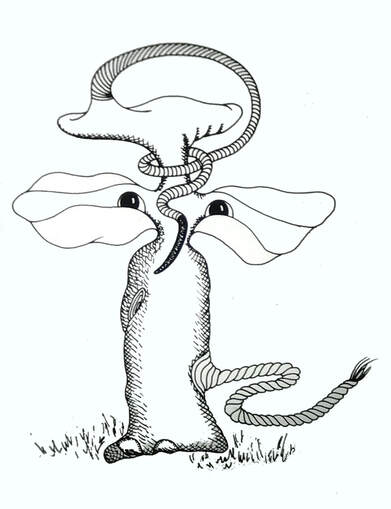

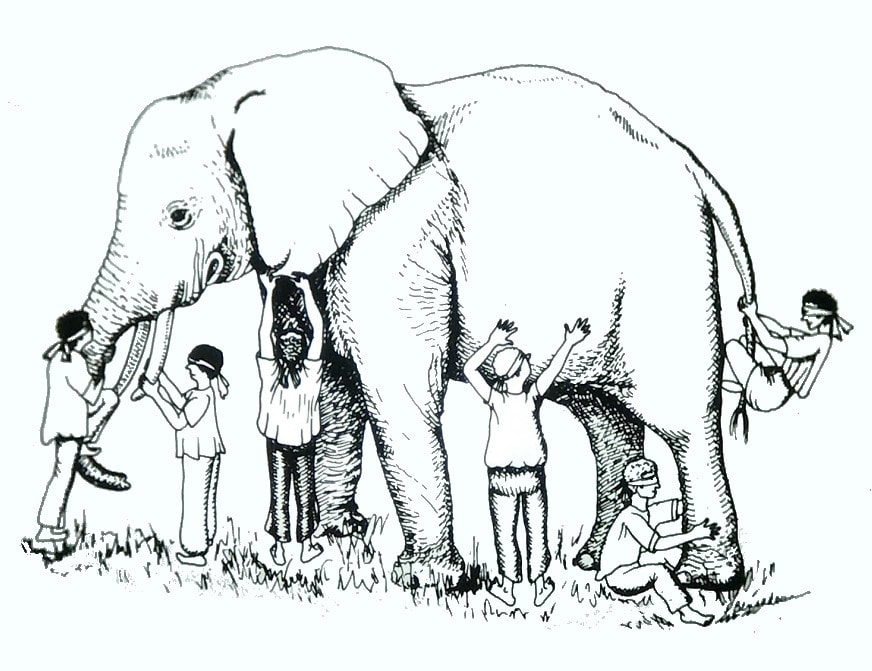

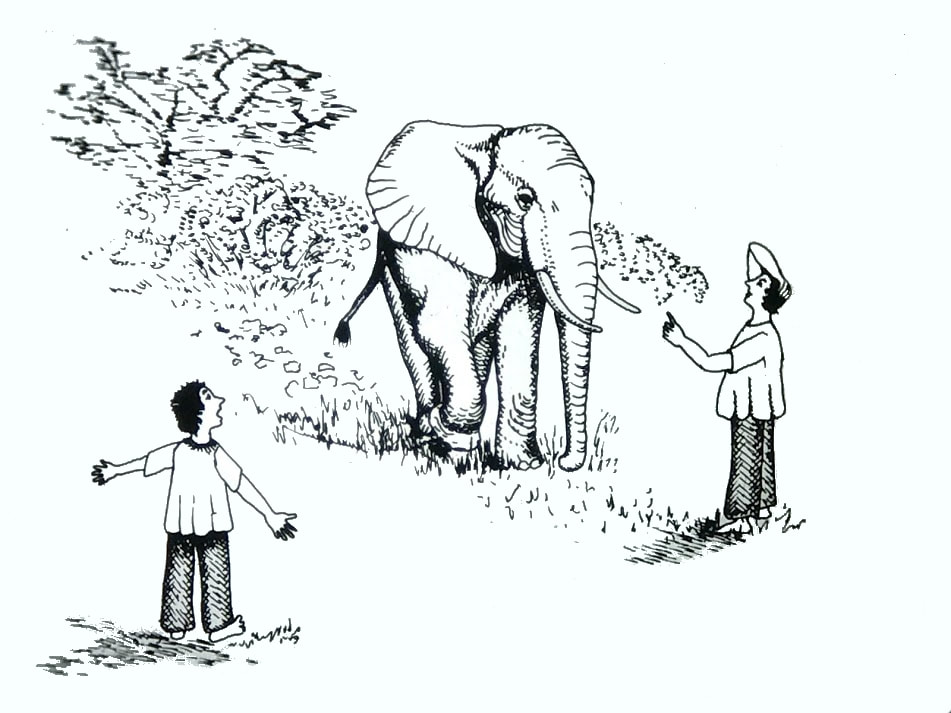

I have tried to explain in my blog how scientific theories arise, and how the initial theories generated in an emerging scientific field are very different from the fully developed theories of a mature scientific field. In this post I will attempt to do this again using the ancient parable of the blind men and the elephant. This is a story found in Hindu and Buddhist texts dating back more than 3,000 years. It has been used in religious and philosophical contexts to illustrate how we often think we know the truth, even though we have just grasped only part of it. The most famous version in English is the poem entitled “The Blind Men and the Elephant” written by the poet John Godfrey Saxe. So let’s imagine a physical reality which in our case has the shape of an elephant, and that we will call “the elephant”. Let’s also imagine an emerging scientific field that is trying to research said elephant. The field is represented by six scientists who seek to figure out how the elephant looks. But the scientists are in the dark as shown by the blindfolds they are wearing. So each of these scientists approaches the elephant and begins to research it. In our story this is exemplified by the scientists touching the elephant. Scientist 1 grabs the elephant by the tail and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a rope. Scientist 2 touches the elephant’s leg and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a tree. Scientist 3 touches the side of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a wall. Scientist 4 touches the ears of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a fan. Scientist 5 grabs the tusk of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a spear. Scientist 6 feels the moving trunk of the elephant and puts forward the hypothesis that the elephant is like a snake. In the various versions of the parable, the blind men quarrel with each other, as each is one is convinced that their version of what the elephant looks like is the truth. The parable ends mocking their hubris at thinking that each one knows the truth when really none of them knows the whole truth (the real shape of the elephant). However, there is one fundamental difference between these versions of the parable and mine. In my version, the blind men are scientists, and that makes all the difference! These scientists are not working in isolation. They discuss and cooperate with each other. Mind you, some of these scientists may argue very forcefully in favor of their particular idea of how the elephant looks, and others may argue back just as forcefully that they are wrong. However, these scientists go to meetings, give presentations, face each other, exchange information, and publish their research results regarding the shape of the elephant in peer-reviewed journals. Each scientist tries to reproduce the observations made by others. The scientist who touched the tail and concluded that the elephant was like a rope, also touches the leg of the elephant, and realizes that he should modify his original hypothesis to incorporate this new information. Thus he proposes that the elephant looks like a tree with a rope sticking out of it. The scientist who touched the side of the elephant and concluded that the elephant was like a wall, also touches the ear, and realizes he should modify his original hypothesis to include this information. He now proposes that the elephant looks like a wall with a fan sticking out of it. The same happens with the other scientists. As new information becomes available, scientists modify their original views and try to harmonize all the knowledge about the elephant. Mind you, this can be a messy process that may be hampered by methodological difficulties. For example, some scientists may not reach high enough to touch the ear, or may not be nimble enough to catch the tail and they remain unconvinced of claims that the elephant is like a fan or a rope. Nevertheless, after a period of time, a majority of these scientists come to an agreement and put out the first theory regarding how the elephant looks!  The First Theory The First Theory As you can see from the image, this theory about how the elephant looks is a very preliminary one. However, there is something “elephant-like” about it. Clearly the theory has grasped some aspects of the reality the scientists were studying. In its present form the theory may even have some usefulness, but the theory is clearly incomplete. It does not reflect the full reality of how the elephant looks. Nevertheless, this theory represents a group effort. The scientists are trying to fit all the relevant information that is available to come up with the answers. So the research continues. A scientist may find that the elephant has not one leg but four. The scientist reasons, “Hmm, the elephant is like four trees? That doesn’t make sense.” Another may find that the surface of the wall is much larger and is connected to the four legs at the bottom and completely surrounds the elephant at the middle. He may think, “What type of wall is this? The elephant may not be like a wall after all.” As more observations keep piling in, the original theory is found to be unsatisfactory and is replaced by one that incorporates the new observations. This new theory is more complete and its image would look more like an elephant. Scientists develop new methods to investigate the shape of the elephant generating more information. Scientists from other disciplines may also take up the research of how the elephant looks bringing in their expertise and new ideas. As this process keeps going and the scientific field that studies the elephant reaches maturity, a theory is put forward that explains the majority of the observations regarding how the elephant looks. The theory is used to make predictions that turn out to be true and generates practical applications. The scientists stop arguing with each other regarding the most relevant aspects of what the elephant looks like, and they reach a consensus. Thus something has happened that has never happened in any of the previous versions of the parable. The scientists studying the elephant don’t have their blindfolds on anymore. They are able to behold the true shape of the elephant. By working together, exchanging information, trying to reproduce what others did, and trying to come up with explanations for all the observations, they have discovered the truth! That is how science works. The images by Paula Bensadoun can only be used by permission from the author.

1 Comment

The scientific consensus has been getting a bad rap lately. Some people argue that whether science is right or not about an issue is not decided by majority vote. Rather, it is claimed, it only takes one scientist to be right to decide whether the science regarding an issue is true or not. Those that make this argument then go on to provide a list of scientists that went against the consensus and prevailed. The people making these argument then proudly proclaim that in science there is no such thing as consensus, that science does not require a consensus, and if there is a consensus, then it isn’t science! Let’s try to understand a few things about the scientific consensus.

A scientific consensus is not reached when scientists get together and “vote”. A scientific consensus, unlike the use of this word in other fields such as politics, does not involve a compromise. Also the word consensus is sometimes used to denote the current state of a field as in “the current consensus”. In a new field of study the term “scientific consensus” really means “the current opinion” and it is understood that such opinion is very likely to be overturned in the future. This is not the meaning of consensus that better serves science in the public sphere when dealing with topics like climate change or evolution. The meaning of scientific consensus that we should seek is that consensus attained in a field of science that is backed by a fully developed scientific theory. A field of science that has not generated a fully developed scientific theory is incapable of generating a true scientific consensus. The reason this is the case is because a fully developed scientific theory has grasped important aspects of reality in its formulation and is likely to have a high degree of completeness. How is such a theory developed? When a field of study is in its early stages, scientists from several countries, ethnic backgrounds, beliefs, political persuasions, etc. begin tackling a problem. All these scientists bring their intellect and life experience to bear on answering the questions being investigated. Initially there is a multiplicity of possible answers, there are uncertainties, deficiencies and limitations in the methodologies, and there is confusion. Many scientists go down blind alleys only to find they have wasted their time on a wrong approach and have to turn back. Some explanations emerge that seem to be better than others. Methodologies are improved. Hypotheses are refined. Exceptions are explained. Scientists from other areas enter the field and bring new tools and ideas (a very important development). The research performed in these other fields is found to be complementary to the research in the emerging field. Eventually as the field matures scientists from different laboratories using different methodologies begin obtaining the same results and elaborate models that they use to make predictions (another very important development). Some predictions are not fulfilled and the models that generated them fall by the wayside and are replaced by new models that are more accurate at explaining the data and making new predictions. Eventually the field coalesces around a theory. The theory is used to generate practical applications and to explain observations in other areas of science. A theory developed through the process described above is not an ephemeral construct that can be overturned at any time. The very technology that we use in our everyday lives depends on hundreds of solid scientific theories that have never been disproven. Many people who do not understand the nature of scientific truth confuse the overturning of a scientific theory with its refinement. This is because there is the erroneous notion that scientific theories should explain everything, and this is not the case. A scientific theory only has to answer the most important questions raised by scientists. Thus, when a fully developed scientific theory is produced in a field of study this means that scientists have stopped arguing with each other about the salient points addressed by the theory. In other words, they have reached a consensus. This is the true meaning of a scientific consensus. Of course, the fact that there is a consensus doesn’t mean that everything has been settled. Scientists that agree with evolution are still debating how evolution happens. Scientists that agree with climate change are still debating its extent and mechanisms. Nevertheless, a consensus does mean that the major overreaching question in the field has been answered to the satisfaction of the vast majority of the scientists involved in the research. The consensus can, in principle, be modified if the underlying theory that backs the consensus is found to be incomplete, but this is only true if the refinements to the theory in the form of new observations, new data, or new interpretations of old data or old observations, significantly modify those parts of the theory that are vital for the consensus. In the case of a fully developed scientific theory this is no easy task, and the burden of proof is on those who seek to modify the theory. Some people claim that this promotes a herd mentality that leads to dissenting scientists being penalized and those that are compliant being rewarded resulting in the discouragement of innovation. However, what has to be understood is that science is a very conservative enterprise that sets a very high bar for those seeking to challenge what is considered established knowledge. If you are going against the prevailing theory, you’d better have very good evidence. This is not the product of a herd mentality or a way to discourage innovation: it is a way of protecting established science against error. In the public debate, when you hear that a consensus has been reached in a particular field of science, you need to ask about the nature of the underlying theory that backs it. If the theory fulfils the requirements of a fully developed scientific theory, then the consensus is good. A consensus is only as good as the theory that supports it. However, suggesting that there is no such thing as a scientific consensus or that it is irrelevant is nothing more than a strategy to delegitimize science. It has been used in the past by entities such as the cigarette lobby, and it is being used today by creationists, climate change deniers, and other groups that seek to further their anti-science agendas. Image by Nick Youngson used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed