|

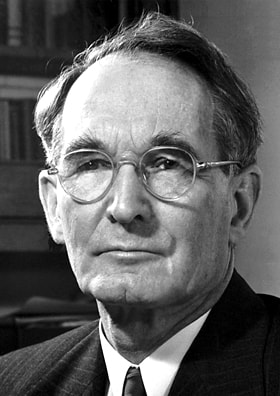

Suicide is often considered an irrational decision, and while that may be the case in conditions like mental illness or dire emotional states, the situation is not as clear when this action is the product of a well thought out end of life decision. Among all people, scientists have the reputation of being smart individuals, and among all scientists, presumably the smartest are those that win a Nobel Prize. There are few Nobel Prize winners that have taken their own lives. Was this irrational? Today we will take a look at these individuals and their motivations.  Emil Fischer Emil Fischer Emil Fischer was a German chemist who was one of the towering scientific figures of the early 20th century, and who is considered the father of biochemistry. He discovered and synthesized many molecules such as caffeine, which is the substance in coffee that keeps you awake, and theobromine, which is the substance that makes dogs sick if you feed them too much chocolate. With fellow chemist Josef von Mering, Fischer made the first of the biologically active barbiturates, barbital (sold as Veronal), which has strong sedative properties. He defined the structure of many carbohydrates and was the first to synthesize glucose, the building block of cellulose and starch. For these and other discoveries, Fischer received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1902. All the foregoing seems to be something positive to feel good about, but unfortunately in the personal realm, things didn’t go as well. Fischer’s wife had died 7 years after their marriage leaving him to raise 3 sons alone. During the First World War, Fischer enthusiastically joined the war effort, coordinating the interaction between industry, academia, and the military. However, as the war dragged on, he became disillusioned with it and the heavy toll it was taking on German society. In addition to this, two of his sons died during the war. Fisher himself developed ill-health due to exposure to some of the compounds with which he worked in the lab over the years. Depressed over the effects of the war on his country and the deaths of his two sons, a diagnosis of intestinal cancer seemed to push him over the edge, and he committed suicide in 1919 using cyanide, one of the compounds he had successfully employed in his research.  Hans Fischer Hans Fischer Hans Fischer was a German chemist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1930 for working out the structure of hemin and performing its synthesis (hemin is the core of the hemoglobin molecule that makes possible the transport of oxygen in the blood), and for his work on the structure of chlorophyll, which is the pigment in plants that makes photosynthesis possible. He also figured out the structure of bilirubin (the pigment that gives sufferers of jaundice their yellow color) and synthesized it. He is not related to Emil Fischer, but he worked as his laboratory assistant for two years. Hans married but never had children. Although he was an avid outdoorsman, he was a man mostly devoted to his work. Unfortunately, his laboratory and most of his life’s work was obliterated during a bombing in the last days of World War II. As a result of this, Fischer fell into depression and committed suicide in 1945 at the age of 63.  John Howard Northrop John Howard Northrop John Howard Northrop was an American biochemist who won the 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work in isolating and crystalizing proteins. One of his critical achievements was demonstrating that enzymes were proteins. Northrop was an enthusiastic fisherman and hunter who remained active into his nineties, but as he got older and weaker, although he remained lucid, he may have viewed his future with concern about becoming a burden for his family and friends. Northrop committed suicide in 1987 at the age of 96.  Percy Williams Bridgman Percy Williams Bridgman Percy Williams Bridgman was an American physicist who discovered that the properties of substances change dramatically under high pressures. His work had a profound influence in areas such as the understanding of Earth’s geology at great depths, and won him the Nobel Prize in physics in 1946. Beyond that, Bridgman was an excellent family man, philosopher, teacher, plumber, carpenter, gardener, and piano player! He was admired and loved by many. So why is his name in this list? Bridgman developed a serious difficulty in using his legs and was afflicted with intense pain and fatigue. He was diagnosed with metastatic bone cancer. When he realized he would be dead in a matter of months he asked the physicians who examined him to provide him something he could take to take his life. When they refused, he committed suicide by shooting himself in 1961 at the age of 80. A note found in his pocket that has been quoted by many proponents of assisted suicide read: "It isn't decent for Society to make a man do this thing himself. Probably this is the last day I will be able to do it myself."  Stanford Moore Stanford Moore Stanford Moore was an American biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1972. His invention of a machine to analyze amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) made it possible to figure out the linear structure of complex proteins and relate their function to their structure. This achievement heralded the “protein era” in biochemistry which had widespread effects on areas ranging from medicine to industry. Moore never married and was not interested in material gain or personal possessions (he never patented any of the methods or instruments he invented). He was extremely organized and led a frugal lifestyle totally devoted to science working long hours and weekends. He was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease), and his mobility and health became progressively impaired. In 1982 at the age of 68 after putting his affairs in order, he committed suicide in his apartment.  Christian de Duve Christian de Duve Christian de Duve was a Belgian cytologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1974 for discoveries regarding the structural and functional organization of cells. His approach of “exploring cells with a centrifuge” brought about a revolution in cell biology and biochemistry, and permitted him to discover two important cell organelles, the lysosome and the peroxisome which in turn helped scientists make many advances and understand the etiology behind dozens of genetic diseases. He considered his life to be “extraordinarily rewarding” and full of “joy and pleasure”, but towards the end he developed a host of health problems including cancer, and suffered a fall that incapacitated him. de Duve lived in Belgium where physician-assisted suicide is legal. In 2013 at the age of 95 de Duve surrounded by his family and assisted by two doctors took his life. One of his daughters said, “He bid us adieu, and he smiled at us, and then he left us.” All the scientists featured here were bright accomplished individuals who changed the world with their work. Whereas dire life circumstances were a component of the decisions made by Emil and Hans Fischer to end their lives, the end-of-life decisions of the rest of the scientists mentioned here had a motivation rooted in infirmity. I do not view the decisions of highly intelligent lucid men like Northrop, Bridgman, and Moore as irrational, but I view the fact that they had to carry them out as secretive affairs alone and away from family and friends as tragic. Contrast their suicides with that of de Duve which was really a formal and celebrated end to an exceptional life. Science cannot tell us whether suicide is good or bad, or moral or immoral - that is the realm of ethics, philosophy, and religion. But I believe that if we are willing to bestow a Nobel Prize to individuals as recognition for achievements that derived from their intellects, we should be willing to be equally gracious when these intellects decide it’s time for an end-of-life decision. And you should not need to win a Nobel Prize to be worthy of this kind of respect. Photo of Emil Fischer by Atelier Victoria (Inh. Paul Gericke, gegr. 1894), Berlin is in the public domain. Photos from the Nobel Foundation of Percy Williams Bridgman, Hans Fisher, and John Howard Northrop are in the public domain. The photograph of Stanford Moore is used here under the doctrine of Fair Use. The photograph of Christian de Duve by Julien Doornaert is used here under an Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5) license.

0 Comments

|

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed