|

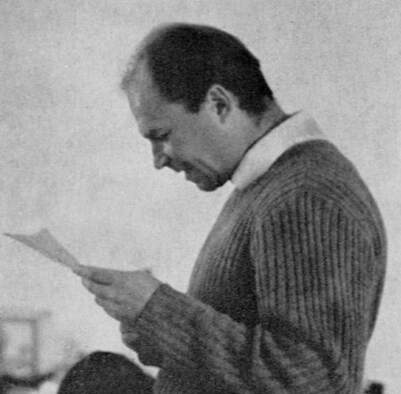

In the current poisoned social climate of public discourse where scientists have been accused of siding with liberal policies and ideas, one thing has been forgotten: science is a very conservative enterprise. What I mean by this is that in science the established theories or accepted ideas are given preeminence over new theories and ideas. Why this is the case is not clear, and to my knowledge this premise has not been formally written into the scientific method. Science may be conservative because new theories that seek to upend the established wisdom have to clear a higher bar, as they have to explain the facts better than stablished theories. Alternatively, science may be conservative because once scientists have settled into working with a set of models and understating phenomena in a certain way, they may not be eager to introduce chaos into their world view. Whatever the reason, most scientists that seek to topple scientific orthodoxy must get ready to face a lot of opposition from their peers.  Piotr Slonimski Piotr Slonimski The geneticist Piotr Slonimski faced this prospect when in 1947 he made a discovery. At the time it was established wisdom that living things require a group of enzymes called cytochromes, which are involved in energy metabolism. Slonimski discovered a yeast mutant that, according to his measurements, did not have any cytochromes. The implications were clear: cytochromes are not necessary for life. Slonimski encapsulated the fear he felt at the moment in his autobiography where he wrote. “Whenever one finds himself at odds with the “conventional wisdom”, as we have called it for a long time, or a “paradigm” as it was renamed by Thomas Kuhn …,there is nothing to expect other than hell from the great unknown presences, and adverse and chilling responses from the people you thought were your friends. There is something profane about upsetting the conventional wisdom… The dispelling of a paradigm is tantamount to being asked to be ostracized, and one can expect to be flayed publicly.” How a scientist will or should handle the introduction of new ideas into the scientific discourse depends on the dynamic of the particular field in which they operate. However, as Piotr Slonimski also wrote, there is only one thing to do and that is to “confront the arbiters of the conventional wisdom”. In his particular case, Slonimski took a sample of his yeast cultures to one of the leading cytochrome experts in the world, David Keilin. He showed up at Keilin’s office and explained he had a yeast mutant that grew normally in the absence of cytochromes. Keilin accepted the sample and went to his lab while Slonimski paced outside. After a while Keilin came out and said “You are right!” Eventually Slonimski and others figured out what was going on. The yeast cells he discovered have a mutation in the DNA of an organelle called mitochondria. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell. This mutation eliminates the cytochromes residing in the mitochondria and renders these organelles unable to function. The yeast cells Slonimski discovered derived their energy by other means. This was a significant discovery that shed light on important aspects of the bioenergetics of cells.  Stanley Prusiner Stanley Prusiner However, it is not always so straightforward to confront the arbiters of the conventional wisdom. In 1972 the American neurologist and biochemist Stanley Prusiner became interested in a type of diseases that caused dementia and death and were thought to be caused by what were presumed to be “slow viruses”. Among these diseases were those like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and kuru that infected humans, and those like scrapie that infected sheep. Prusiner decided to figure out what was the causative agent of these diseases, which at the time was a daunting problem as the available assays were slow and expensive. Over the next decade he produced many preparations of the infectious agent only to find that these preparations contained protein but not nucleic acids. Moreover, the infectiveness of these preparations was eliminated by agents that destroyed proteins but not nucleic acids. This was a noteworthy observation because viruses (and in fact all living things) require nucleic acids to make more copies of themselves. Eventually he came to the conclusion that the infectious agent was exclusively composed of protein which was a concept that ran contrary to the prevailing wisdom that an infectious agent must contain nucleic acids. In an article published in 1982 he officially made this heretical claim christening the infectious agent “prion” (derived from protein and infectious). The reaction of the scientific establishment was swift and vitriolic. The concept of the prion was ridiculed in public and private, and at every scientific meeting he attended Prusiner was lambasted with a barrage of criticism. An anonymous satirical limerick was even circulated among the laboratories in the field and quoted by journalists: There was a young turk named Stan Who embarked on a devious plan. "If I simply rename it, I'm sure I can claim it," Said Stan as he pondered his scam. "Eureka!" Cried Stan, "I have found it. Well...maybe not actually found it. But I talked to the press Of the slow virus mess, And invented a name to confound it!" Through all this Prusiner persevered. He discovered the Prion protein and the gene that coded for it and found that the difference between the infectious protein and the normal protein was the way it was folded. More significantly, Prusiner found that the infectious protein can alter the folding of the normal protein making it infectious. This represented a truly novel mechanism of disease causation. During this time not only did other scientists fail to discover any nucleic acids associated with the putative slow viruses or with prions for that matter, but scientists that tried to replicate Prusiner’s work obtained the same results. Eventually the scientific establishment gravitated towards Prusiner’s ideas and he received one prize after another culminating in the Nobel Prize in 1997. Despite the above stories, the plight of the lone visionary scientist fighting the system to get a radical idea accepted should not be romanticized. As Prusiner himself declared: "Most radical ideas turn out to be incorrect. It is very important that the people who propose new ideas be given a tough time." For each scientist that upends the established wisdom in their fields there are dozens of others whose ideas never gain traction among their peers because they don’t explain the facts well or because the experimental results on which they are based cannot be replicated by others. So next time you read in the press about the latest liberal-related slur levied against scientists remember that in its essence (to paraphrase what Stephen King wrote in his book Danse Macabre, albeit in a completely different context) science “is really as conservative as an Illinois Republican in a three-piece pinstriped suit”. The pictures of Piotr Slonimski and Stanley Prusiner are in the public domain

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed