|

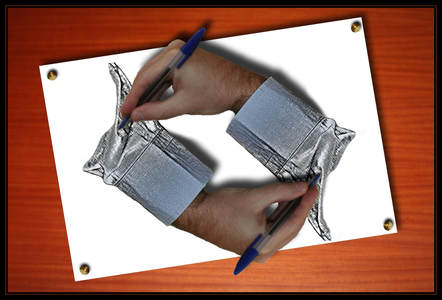

I an earlier post I wrote that anyone can be a scientist. The only requisites are to follow the scientific method and ask scientific questions. Scientific questions are those that can generate testable answers (hypotheses). Scientists ask these questions. That seems like a very straightforward concept, right? As it turns out, there is a lot of subtlety involved in asking scientific questions. In fact, I would argue that asking scientific questions is not a science, it’s an art, and I believe that there are three levels of complexity in the process of formulating effective scientific questions First level: Asking questions within the right framework While both amateur and professional scientists may be “scientists”, asking minor scientific questions just for fun or curiosity is very different from asking important goal-oriented scientific questions within the context of a funded research project. The relative difference is much the same as the difference between playing in your neighborhood baseball team and playing in the major leagues. At the professional level, more than a decade of training and study is required for participants to both mature and master the intricacies of science and the methods within a particular field of study. This is because the complexities of the questions that are addressed by professional scientists are very unlikely to be answered unless they are articulated within this context. Effective questions are those queried within a framework that leads to their eventual solution.  Second level: Asking questions while having in mind a way to answer them Some scientists may formulate a question and then seek the answer. This perfectly logical procedure, paradoxically, is not an optimal way of asking scientific questions. This is because it is not enough to ask a question. You need to have an idea or a hunch as to how you are going to answer the question, and this idea or hunch inevitably affects the formulation of the question. The question refines the answer which refines the question which refines the answer and so on. The process is not unlike the one depicted in the lithograph by the Dutch artist M.C. Escher where the first hand draws the second one which in turn draws the first. This process allows for the solution of scientific problems with razor sharp accuracy, and it requires an in-depth knowledge of the fields of science involved, as well as the capacity to integrate, simplify, and pick and choose relevant data from large amounts of potentially conflictive information. The ability to master this process is often the difference between clear thinking and fuzzy thinking among scientists. Third level: Asking “THE question” type of questions

The Nobel Prize winning biochemist, Hans Krebs, used to tell new arrivals to his lab that he could teach them how to dig, but he could not teach them where to dig. By this he meant that he could teach them all the necessary techniques, ways of thinking, and approaches to answer questions, but what he could not teach them was what questions to ask. To non-scientists (and even to a good number of scientists) this may seem odd. After all, what can be so possibly complicated about asking a question? The answer is, of course, nothing. There is nothing complicated about asking “A question”, but this was not what Krebs was talking about. He was talking about asking “THE question”. This distinction is a very important one. A researcher capable of asking “THE question” type of questions is to a researcher only capable of asking “A question” type of questions what an architect is to a bricklayer. The truth is that most scientists are incapable of asking “THE question” type of questions and many are not even aware that this is a limitation. Indeed, a good number of researchers would even dispute that this is an issue. These researchers have trained with other scientist who only asked “A question” type of questions, and that is all they know. From their vantage point this is how science works. You ask a series of little specific questions and subject them to test and make incremental advances that build upon each other. Now, I don’t want to imply that asking “A question” type of questions is not useful. Large numbers of researchers asking these type of questions produce valuable information that moves scientific fields forward, and when these researchers team up with applied scientists this results in practical applications. These scientists create the stepping stones on which science advances most of the time. However, it is the scientists who have the ability to ask “THE question” type of questions the ones who are responsible for the milestones. These scientists have the depth, vision, and inspiration to, going back to Krebs’s analogy, know “where to dig”. And as Krebs pointed out, this ability is something that can’t be taught. The scientists who ask these questions that get to the fundamental nature of things are very much like the artists who have the ability to create a masterpiece that will endure through the ages and captivate the imagination. I consider that, in terms of asking questions, level 1 separates the professional scientists from the amateurs, level 2 separates the good scientists from the average ones, and level 3 separates the truly exceptional scientists from the merely good ones. Of course, there is more to successful science than asking questions. There is luck, there is being at the right place at the right time, there is the capacity to promote yourself and your research, to network, to establish collaborations, to request funds, and many other activities that are not mastered by locking yourself up in a lab or an office and thinking up questions. However, those scientists who can function at level 3 are in the highest echelon of sophistication in the art of articulating scientific questions, and this is pretty darn close to the stuff Nobel Prizes are made of! Escher-inspired figure by Robbert van der Steeg used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed