|

In the excellent 1987 docudrama, Life Story, also known as The Race for the Double Helix, which dramatizes the discovery of DNA, Dr. Rosalind Franklin played by actress Juliet Stevenson complains to her colleague Dr.Vittorio Luzzati about leaving Paris to go to London to continue her work. “Why am I leaving Paris? She asks. Vittorio replies, “My dear Rosalind, you must turn your back on thoughts of pleasure. We are the monks of science.” To which Dr. Franklin adds, “And the nuns.” Vittorio’s comment was intended as a joke, but it did frame very well the attitude that scientists have had towards scientific work. Indeed at times the all-consuming devotion of scientists for their work has been reminiscent of a monastic class of individuals who make vows to eschew Earthly delights in favor of a chance to make scientific discoveries. This devotion and its associated work ethic were transmitted from one generation of scientists to another through teaching and example. I had a friend who, while pursuing his studies in medicine, had been accepted to carry out basic research once a week in the lab of a professor of certain renown. The first day he went to the lab he was pretty excited, and was thrilled that the professor stayed with him performing experiments until late at night. At the end of the workday the professor asked him, “At what time are you coming tomorrow?” Somewhat puzzled, my friend tried to explain that he could only come to the lab once a week. However, the professor would have none of it and insisted he come again next day. So my friend returned to the lab next day and he stayed until late again performing experiments with the professor after which the professor again asked him, “At what time are you coming tomorrow?” This went on for a week, and my friend was pretty wiped out, so he made it a point of explaining to the professor that this could not continue. He told him that not only did he have classes and patients to attend, but he also had a family. The professor was not impressed and replied, “When I was your age, I had a family, and I was in medical school too. I had to attend patients, I had to take classes; and I also had to pay my professors for teaching me”. Then he added, “I am not charging you anything. At what time are you coming tomorrow?”  These stories of sacrifice and devotion to scientific work were once very commonplace. I have known of scientists who worked so hard that they started sleeping in their labs because it made no sense to go back home at the end of the workday. I knew a scientist who one day arrived home just to find his infant daughter was speaking. He quizzed his spouse as to when this had happened, and she just replied, “While you were away in the lab.” He had missed her first words. I knew of a scientist who one day in the fall began a period of intense work and concentration in his research. He worked for months eating at his research institute’s cafeteria, and sleeping in the student lounge. After he achieved what he had set out to do, he decided to step out of the building for a change, and realized that it was spring. He had worked through winter! There were research institutes where working weekends and holidays was something that was (unofficially) “expected from you”. In these places, it was virtually impossible to have a chance at succeeding without devoting the extra time. As recently as 3 years ago, I was endorsing the application of a student to a research position, and as one of the plusses I said that if necessary he would come to work on weekends. There was a long silence on the other side of the phone, and then the person with whom I was speaking said in a sarcastic tone, “If necessary?” The sacrifice and devotion were not restricted merely to the amount of work that you would put into it, but also to the monetary compensation you received. I had a professor who often remarked how happy he was to be doing science, and how astonished he was that he was actually getting paid to do it. This attitude was very common in the older generations of scientists. Some of these scientists were scandalized when new generations of students started arguing that they had a right to be funded. When they were students, most of these older professors had been content just to have the honor to work alongside great scientists; salary was merely an afterthought. This mentality was so prevalent that it transcended into the broader society. I know of a colleague who once received a phone call from a human resources person to provide him information regarding a position to which he had been accepted at a company. However, he considered that the pay he was offered was too low and he tried to negotiate a higher salary. The human resources person was confused by this request and quizzically asked, “Why do you want a higher pay, aren’t you a scientist?”

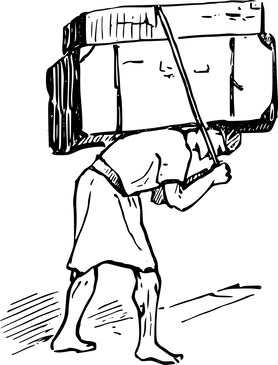

The above are some of the myriads of stories out there of a culture that stressed scientific work above everything. The stereotype of scientists, according to this culture, are the individuals that work 80 hours a week and are happy to be doing what they like, regardless of the amount of salary they are receiving. I once even read an advice to young scientists stating that they should not get married too early in their careers because that would destroy their creativity! However, this culture is fading, and I think this is due to the confluence of several factors. 1) Nowadays there is an excess of scientists contending for an ever dwindling set of academic positions and resources. Competition for funding is fierce, and mere hard work and devotion to science is no guarantee of having your own lab and a successful career. 2) Many sources of employment outside academia have opened up for scientists, and it has become acceptable to have non-academic careers in science. At the turn of this century for a scientist to accept a job in industry was still referred to in some venues as “selling out”. This is not true anymore. Many scientists have flocked to occupations in industry, government, and other areas where they are able to earn decent wages and have a life. 3) Science used to be a male-dominated profession. It is easy for a man to “devote his life to science” if his wife can stay home and take care of the kids. In today’s world where both spouses work, this model is not feasible anymore. 4) Finally, I think that society has grown more cynical and selfish, and this is not necessarily all bad. If young individuals are contemplating devoting the best years of their lives to a given enterprise, they are asking more and more the question: what’s in it for me? The hallowed halls of science nowadays have fewer monks and nuns! The image is in the public domain

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed