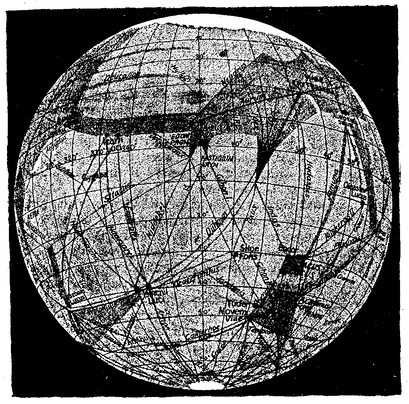

There is a joke that illustrates misguided science thinking. A man is in a public area screaming at the top of his lungs. When somebody comes over and enquires why he is screaming, the man replies, “To keep away rogue elephants”. When told that there are no elephants for miles around, the man replies that this is proof his screaming is working. If you think that is silly, consider the following recipe for obtaining mice by spontaneous generation (in other words, without the need for male and female mice): Place a soiled shirt into the opening of a vessel containing grains of wheat. Within 21 days the reaction of the leaven in the shirt with the fumes from the wheat will produce mice. No, I’m not kidding you! For many centuries some of the best minds in humanity believed that life could regularly arise spontaneously from nonlife or at least from unrelated organisms. Some people went as far as outlining procedures to achieve this, such as the one presented above to generate mice supplied by the chemist Jean Baptiste van Helmont. Presumably, this individual (who is no stranger to misguided scientific thinking) placed a shirt in a vessel with grains of wheat, and when he checked 21 days later he saw a mouse scurrying away. Therefore, he concluded that the mix of the wheat and the shirt in the vessel produced the mouse. What the above examples of misguided science have in common is the ignoring of alternative explanations. In the case of the joke, the alternative explanation obviously is that there are no rogue elephants nearby to begin with. In the other case, the alternative explanation is that the mouse came from elsewhere, as opposed to arising from the shirt with the wheat. The best scientific experiment is one carried out in such a manner that alternative explanations for the experimental results are minimized or ruled out altogether. The ideal scientific experiment should only have one possible explanation for the outcome. In order to achieve this, scientists use controls. A control is an element of the experimental design that allows for the control of variables that could otherwise affect the outcome of the experiment. In the case of the joke, the man could stop screaming to see if rogue elephants show up, or he could scream next to an actual elephant to see if screaming works. In the case of the real example, van Helmont could have placed a barrier around the shirt with the wheat to rule out that mice came from the outside. The use of controls in experiments is so commonplace nowadays, that it is really hard to imagine how anyone could even think of performing an experiment without them. However, the modern universal notion of controls as a way of controlling variables to rule out alternative explanations to experimental results did not begin to take shape until the second half of the 19th century, even though scholars claim that strategies to make observations or experiments yield valid results go back further in time to the Middle Ages or even antiquity. In science, the controls that are most often used are those involving outside variables that can affect the results of an experiment. However, the more important and more challenging variables to control are those that arise from within the experimenter.  Illustration of the Canals on Mars by Percival Lowell Illustration of the Canals on Mars by Percival Lowell If the procedure to make an observation or evaluate the results of an experiment depends on a subjective judgement made by the experimenter, as opposed to, for example, a reading made by a machine, then subtle (and not so subtle) psychological factors can influence the result depending on the biases of the experimenter. I have already mentioned the famous case of the scientist René Blondlot who in 1903 announced to the world he had discovered a new form of radiation (N-rays), but it turned out that such radiation existed only in his imagination. Another famous case was that of astronomer Percival Lowell who, at the turn of the 19th century, thought he saw canals on Mars which he considered to be evidence of an advanced civilization. He was a great popularizer of science and he wrote several books about Mars and its inhabitants based on his observations, but the whole thing turned out to be a delusion. To avoid this type of mistake, many experiments that rely on subjective assessments employ a protocol where the observer does not know which groups received which treatments. This is called a blind experimental design.

An additional challenge occurs when a scientists works with human subjects. Psychological factors can have a potent role in influencing the results of medical experiments. Depending on the disease, if patients are convinced that they are receiving an effective treatment, and that their condition will improve, said patients can display remarkable improvements in their health even if they have received no effective treatment at all. To rule out the effect of these psychological factors, scientist performing clinical trials include groups of patients treated with placebos. Placebos are fake pills designed to mimic the actual pill containing the active chemical substance or ineffective procedures designed to mimic the actual medical procedure in such way that the patient cannot tell the difference. To also rule out the influence of psychological factors arising from the doctors giving patients in one group a special treatment, the identity of these groups are hidden from the clinicians. Clinical trials which employ placebos and where both the patients and the clinicians don’t know the identity of the treatments, are called double-blind placebo-controlled trials, and they are the most effective and also the most complex forms of controls. Unfortunately, the use of controls is not always straightforward. I have already mentioned the case of the discovery of polywater which was heralded as a new form of water with intriguing properties that promised many interesting practical applications until someone implemented a control and demonstrated that it was the result of contamination. Sometimes scientists do not know all the variables affecting an experiment, or they may underestimate the effect of a variable that they have deemed irrelevant, or they may misjudge the extent to which their emotional involvement in conducting the experiment may compromise the results. Designing the adequate controls into experimental protocols requires not only discipline, discernment, and smarts, but sometimes also just luck. In fact, some scientists would argue that implementing effective controls is not a science but an art. The art of the control! The Elephant cartoon from PixaBay is free for commercial use. The Illustration of Mars and its canals by Percival Lowell is in the public domain.

2 Comments

8/11/2019 12:22:56 am

Since seeing this TED talk by Professor Lisa Simpson I have carried a tiger-repelling rock in my pocket... I am pleased to report that to date I have not been eaten by a tiger... “Science! Working for you since the Big Bang”

Reply

Rolando Garcia

8/14/2019 03:48:51 pm

Excellent example, Harvey. Thanks for your comment!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed