|

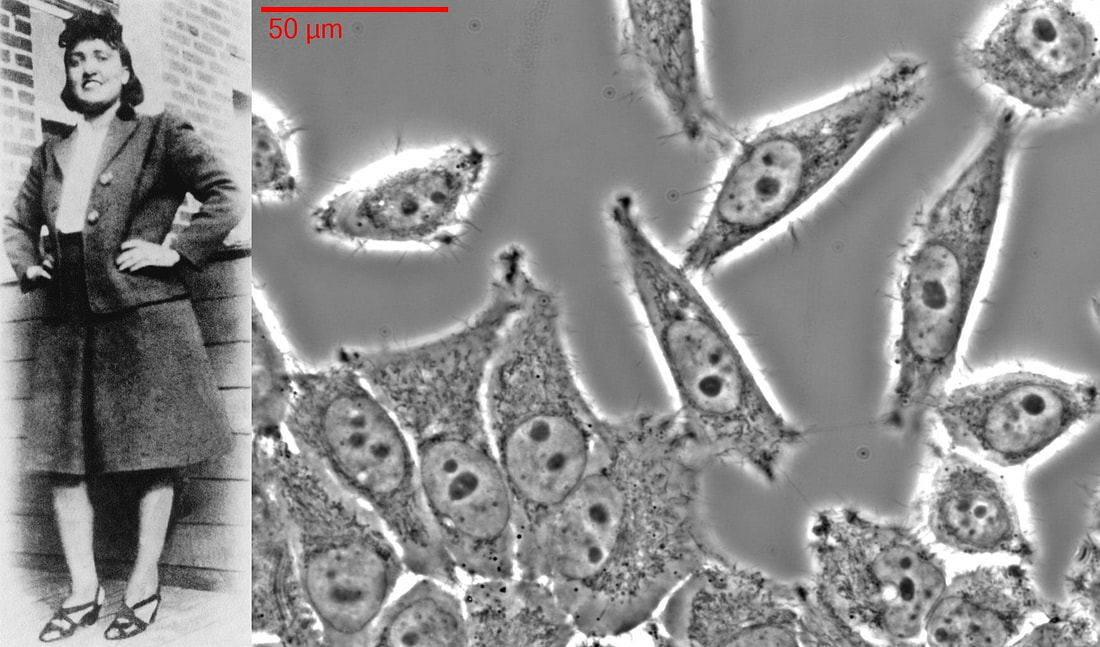

The development of the capacity to culture cells ushered in a revolution in the biological sciences because it allowed scientists to remove cells from the great complexity of the live organism and grow them in a controlled environment where they could study the chemical and physical changes that the cells exhibited during their life cycle in response to both normal and pathological stimuli. The nature and role of many molecules and fundamental processes going on in living things have been discovered thanks to cell culture research, and this has in turn allowed the development therapies for many diseases. Additionally, cells have also been used as tools to screen for new drugs, grow pathogens, test the effects of changes in genes, and in the future may allow the creation of replacement organs. During my scientific career, I have worked with many cells including human cells. Most of the human cells I have worked with were cancerous cell lines derived from tissues such as breast, pancreas, ovary, colon, and cervix. The way these cell lines are generated is that they are initially isolated from a cancer found in an organ, and they are then grown in culture flasks for several generations. Once enough cells are available, they are frozen and stored under conditions that do not harm them, and they can be packed in dry ice and shipped to laboratories around the world. Nowadays you can buy these cells from companies that have divisions that are specialized in cell culture. When I do an experiment with human cells, I am primarily focused on getting the science and the procedure right. However, when I peer through my microscope at those tiny things that swarm and multiply in my culture flasks, I sometimes wonder about the human beings from whom they were taken. Who were these individuals? What did they do? Where did they come from? What challenges did they face in life? What were their opinions about local and world events and trends? What foods and music did they like? What books did they read? Were they killed by their cancers? How would they feel if they knew that I am looking at cells from their breasts or their prostates? When you purchase a cancer cell line, there is very little information available regarding the person from whose cancer the cells were generated. Normally only the age, sex, and ethnicity of the person are provided. Consider the most famous of all cell lines: the HeLa cell line. This was the first cell to be cultured, and it played a crucial role in the process that led to the development of the polio vaccine. The HeLa cells were isolated from a cervical cancer which killed a black woman named Henrietta Lacks in 1951. Since then, these cells have been extensively used for research all over the world and the story of Henrietta Lacks and her cells has been told in a remarkable book by Rebecca Skloot entitled, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. But if you purchase a vial of HeLa cells today, the only information presented regarding the person from which they were obtained is: Age: 31 years adult Gender: Female Ethnicity: Black There is extensive documentation regarding the genetic, biochemical, and physiological characteristics of the cells, as well as information regarding how to grow them and references to their use in research, but there is no information about Henrietta and her life. And some scientists would argue that, in addition to privacy issues regarding the individuals and their families, this is OK because cells are a tool, and any personal information regarding the individuals from which they originated is irrelevant.

Although I understand this argument, I still would like to know a little more about those individuals whose cells I am culturing and how they feel about it. I believe that if someone is donating their cancers to research, they should be given the option to at least write a few lines to the scientists that will be using their cells. For example: Dear Researcher, My name is Jane Doe. My doctors tell me that the cancer they will remove from my ovaries will be used to produce cell lines for research. I am praying that the surgery and the chemo will work, and that I will be able to spend more time with my daughter and my grandchildren. However, I want you to know that regardless of the outcome, I want you to make good use of my cells and find ways to treat this and other diseases. We all appreciate more time in this world, and I hope that God guides your studies and blesses you with clarity. When you peer through your microscope and look at my cells, I may be long gone, but remember that you will be handling a part of me that will outlive me and which represents a little of what I once was. So please take care of my cells and good luck in your research! or Dear Scientist, My name is John Doe. I have lived through a lot. I have been in wars. I have been shot. I have stared death in the face many times and survived. So it’s a bit ironic that this colon cancer may be the thing that brings me down, but we all sooner or later have to accept our fate. The doctors say they will use the cancer they take out from me to produce cells for research. It feels a bit strange to know that there will be a bunch of strangers handling cells from my colon, but if this helps to treat this disease, I am all for it. I love my country, and I value the time I spend with my family, and with my fellow vets when we get together to have some beers every now and then. I would appreciate any extra time I can spend with them, but if I can’t do it anymore, I hope your research will allow others that chance. So please make good use of my colon cells and have a beer for me next time you go to a bar with your research buddies. Godspeed. Including notes such as these in the information available in human cells used for research would give a little more humanity to the process as well as perspective and motivation for those of us using these cells. HeLa cell photograph from Fraunhofer-Institut für Biomedizinische Technik, St. Ingbert, Paul Anastasiadis, Eike Weiß is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license. The photo of Henrietta Lacks from the Oregon State University Flickr webpage is used here under an Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed