|

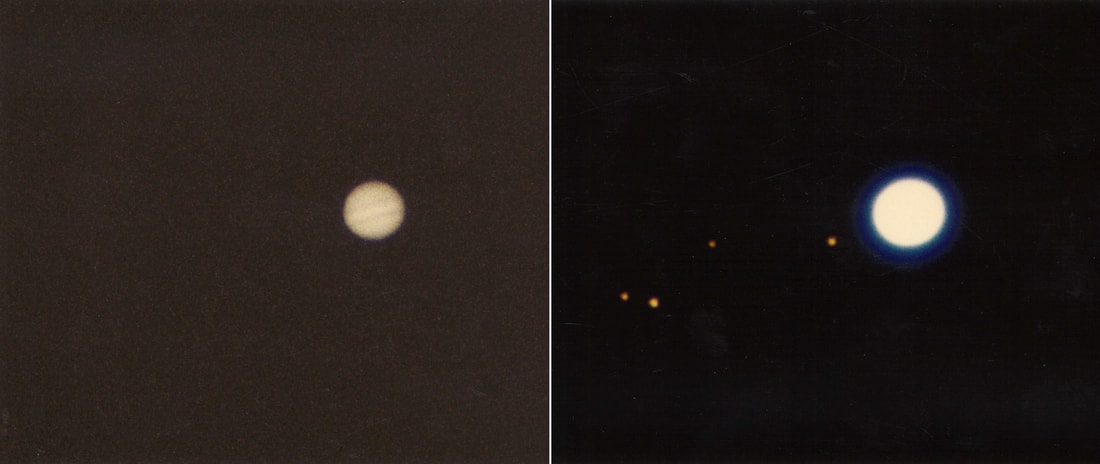

One of the cornerstones of science is reproducibility. This means that if one scientist performs an experiment and gets a result, then other scientists should be able to perform the same experiment and get the same result. This also means that if one scientist evaluates something and makes an observation, other scientists should be able to evaluate the very same thing and make the same observation. This is the way scientists convince themselves that what other scientists find is true. This is also how scientists build a consensus. But if the gold standard for acceptance of experiments and observations as true among scientists is reproducibility, what is the gold standard for the acceptance of experiments and observations as true by those who are not trained scientists? How is a layperson to decide if what scientists are saying is true? The answer to this question is that, to a certain extent, the criterion is also reproducibility. People interested in reproducing some results of scientific experiments and making the same observation made by scientists can also do it. For example, you see all those amazing pictures of planets and galaxies, but how do you know they are true? How do you know if scientists did not just create these by manipulating images? Well, you can buy yourself a telescope or go to a place where they have one. I’m not an astronomer, but a long time ago I visited Fuertes Observatory at Cornell University. The observatory has a 12 inch telescope with a clock drive mechanism to compensate for the Earth’s rotation, which means you can take timed exposures. These types of telescopes are no longer used by astronomers, so the observatory is operated by the students in the Astronomy Department and is open to the public. I spent several nights there and hooked up my camera to the telescope to take pictures of heavenly bodies. I took a photograph of the planet Saturn and its rings. I was also able to photograph Jupiter, and I managed to capture the two large equatorial belts of the planet in the picture. When I took a longer exposure, I could make out Jupiter’s largest moons, Callisto, Europa, Ganymede, and Io. These moons were observed for the first time by Galileo in 1610. I took a picture of the moon. You can clearly see large craters with a lot of lines radiating from them such as Tycho (large crater at the bottom of the picture) or Copernicus (large crater at center left of the picture). The light areas are called highlands, and the dark basaltic plains are called maria (seas in Latin). I was also able to take this picture of the Andromeda Galaxy with its two satellite galaxies, the dwarf elliptical galaxy NGC205 (the fuzzy bright spot below the center of the picture to the right) and the dwarf compact elliptical galaxy NGC221 (the large bright spot to the left of the center of the picture). So I verified that some of these planets, planet features, and galaxies that you read about and see pictures of are true. They are there to see for anyone who takes the trouble to look at them the right way. The above is just merely making an observation, but you can also perform experiments. I wrote a post regarding a famous experiment that you can execute in your own home to reveal that light has wave-like properties. Similarly, there are dozens of books, videos, and websites describing many classic experiments that people not trained as scientists can perform by themselves. So you see, you don’t have to take the scientist’s word for it, you can actually do these experiments and make these observations yourself! Unfortunately, there are limits to this approach. My photographs are nowhere near as fabulous as the detailed close-up pictures of planets and galaxies obtained by space probes or space telescopes, and I can’t build a probe or a telescope and launch it into orbit or send it to faraway planets. There are certain experiments and observations that require specialized equipment that is very expensive and requires special knowledge and training to use. There are certain experiments and observations that may involve cooperation between many scientists and hundreds of other people to make things work and may require years to carry out. Performing these experiments and observations in your backyard or in your basement over a few days is simply not possible. What do you do in these cases? How do you verify that what scientists find is really true? The answer is: you can’t. Like I wrote in a previous post, for some things we rely on several safeguards to maintain scientific integrity such as scientists trying to reproduce each other’s results and the reporting of scientific misconduct to research integrity agencies. But the question is: When hundreds of scientists from different fields come together and agree that their results point in the same direction and reach a consensus, when several competing scientists check each other’s results and find them to be true, when research integrity agencies and other scientific review boards find no evidence of scientific misconduct in the process that generated this consensus, do you then trust the science and the scientists? For the average person, the acceptance of a scientific consensus that depends on experiments and observations that are too complicated for said person to reproduce or sometimes even understand in detail, depends on trust. And herein lies the problem we are facing today. This trust is being eroded by those that seek to disavow science. There are many people who maintain that scientists are lying to the general public and faking or misrepresenting their data because they have sold out to corporations, the government, or other organizations. Among those who hold this view are those who deny the severity of COVID19 or the effectiveness of mitigation measures, those who deny climate change, those who are opposed to vaccination, those who advocate creationism/intelligent design, and those who accept various conspiracy theories ranging from 911 being an inside job to Chemtrail or flat Earth proponents Science is the best tool we have to discover the truth about the behavior of matter and energy in the world around us, and scientists are the specialists who train for many years to wield this tool effectively. Those who wish to subvert the truth to defend harmful products, promote political or religious views of questionable validity, or peddle conspiracy theories that are at odds with truth, know very well that in order to be successful, they must disavow science. This is because science is the only discipline that can prove them wrong. And the best way to do this is to break the trust that people would otherwise have in science. Once this is achieved, people become impervious to facts, and we transition to living a fiction. The photographs belong to the author and can only be used with permission.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed